Yoko Ono

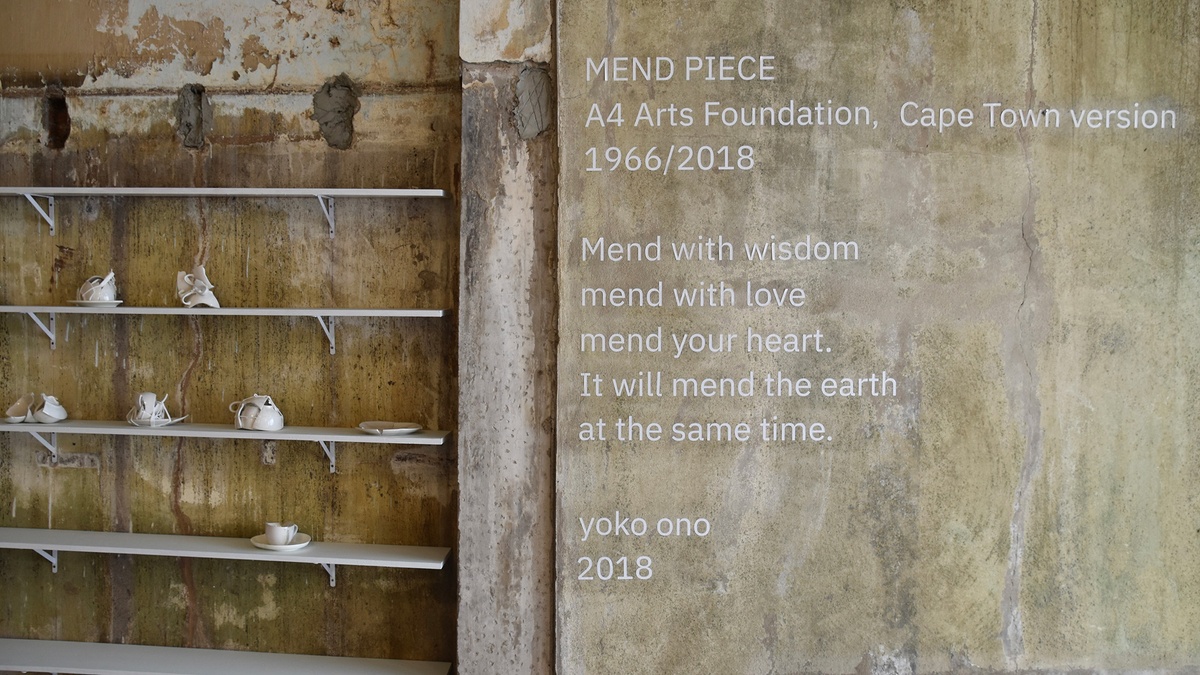

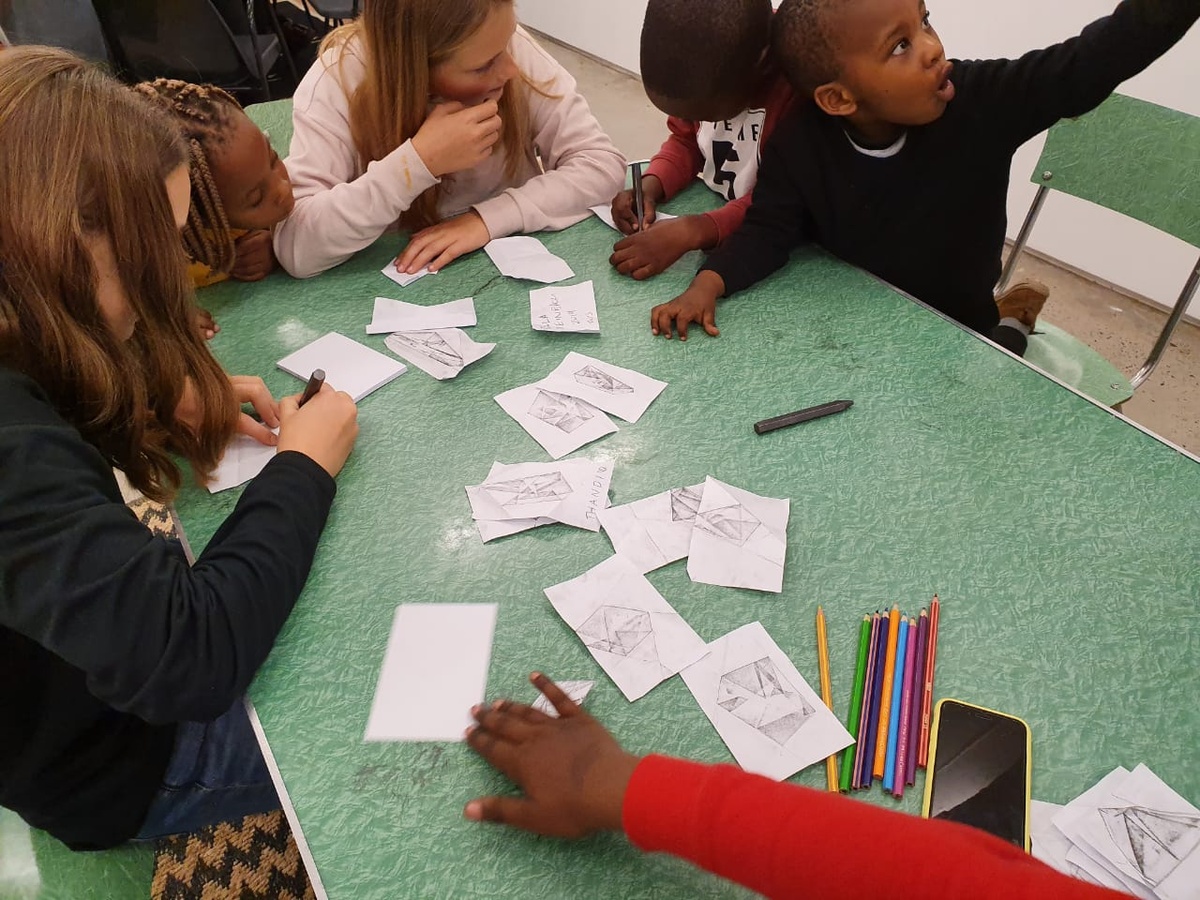

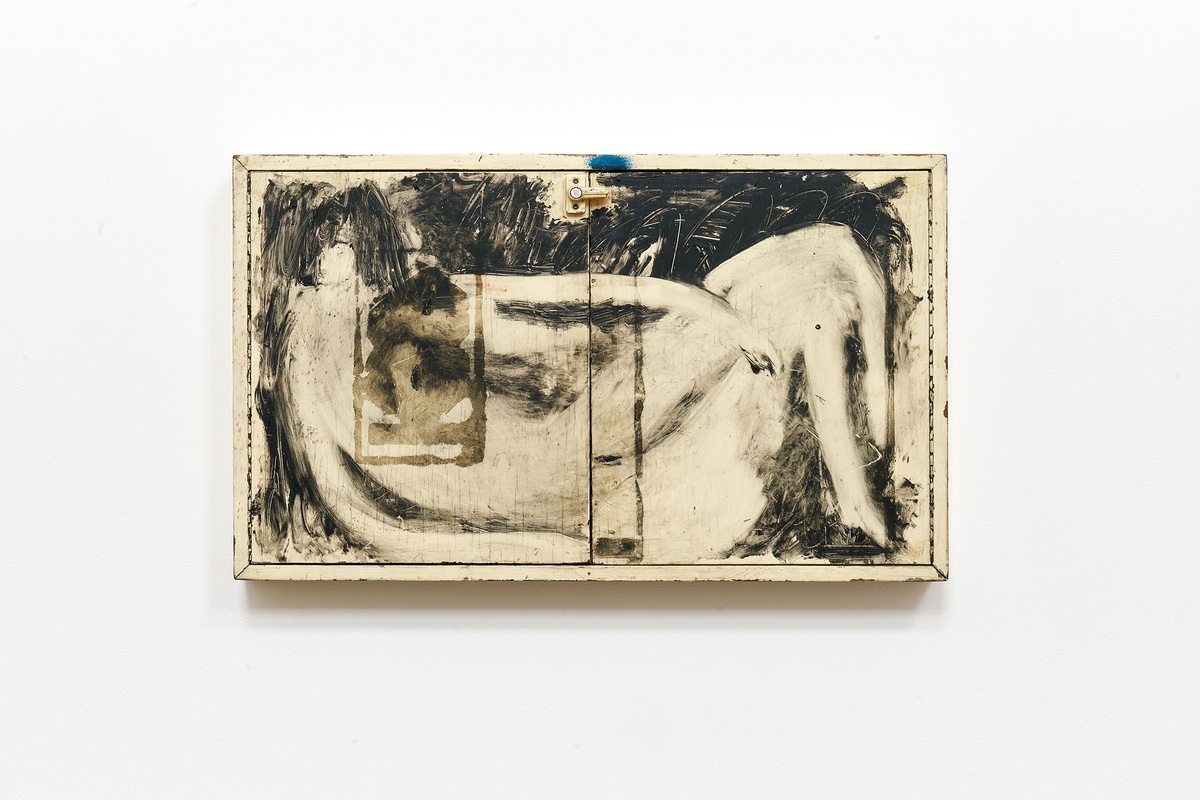

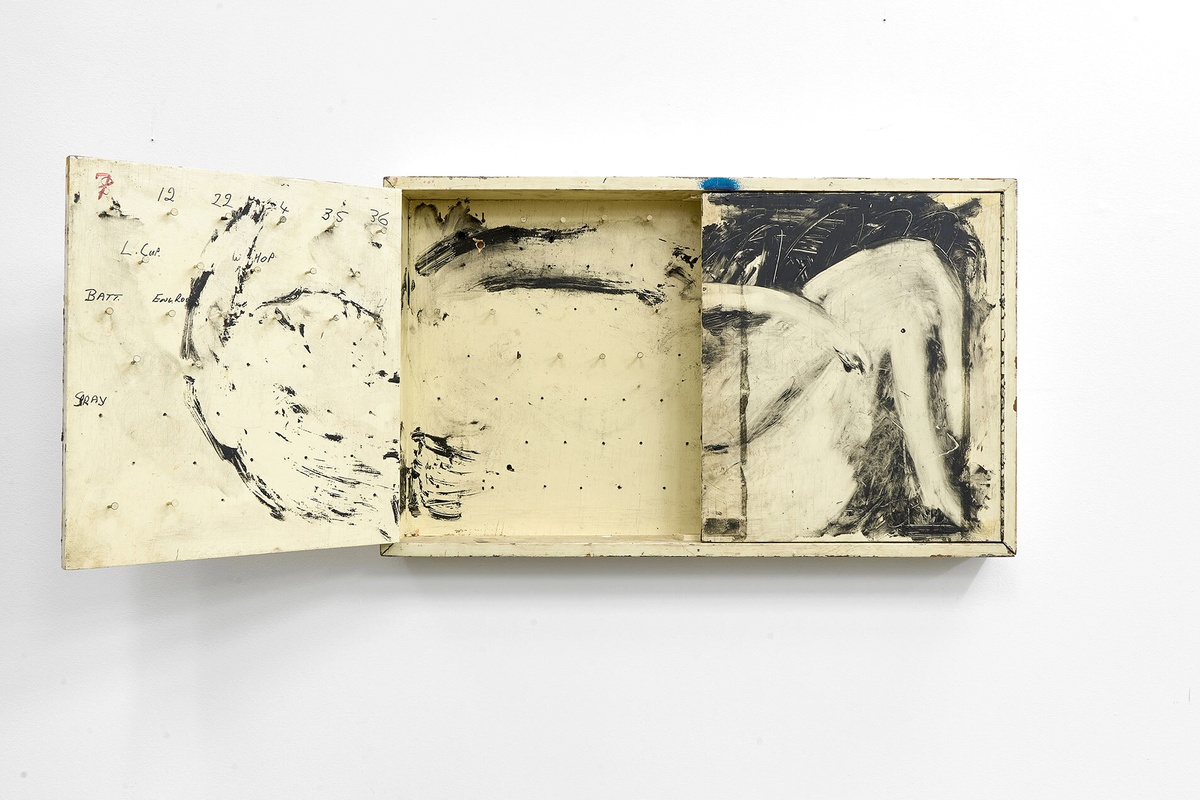

In MEND PIECE, Ono invites the viewer to repair the impossibly broken, to compose splintered parts into a new imperfect whole. To the artist, the simple act of mending is one of both personal and universal significance. “MEND PIECE,” she says, “is a wish piece,” a supplication to healing. This iteration of the work, the Cape Town version created by the artist in 2018, reads:

Mend with wisdom

mend with love

mend your heart.

It will mend the earth

at the same time.

Unable to restore the many broken pieces to their previous forms, the viewer must instead imagine them anew – no longer cups and saucers, but abstract notations of time spent and care taken.

Editor’s note: In 2017, A4 brought Yoko Ono's MEND PIECE to Cape Town, the work kindly loaned to the foundation by the Rennie Collection in Vancouver. This was the New York version of MEND PIECE and it appeared in the first group exhibition at A4 held to celebrate its opening, titled You & I. The version realised through visitors' participation in the exhibition Customs at A4 is a MEND PIECE for Cape Town that has been in A4's care since 2018, and remained unopened. Customs marked the first performance of Yoko Ono's MEND PIECE, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town version (1966/2018).

b.1933, Tokyo

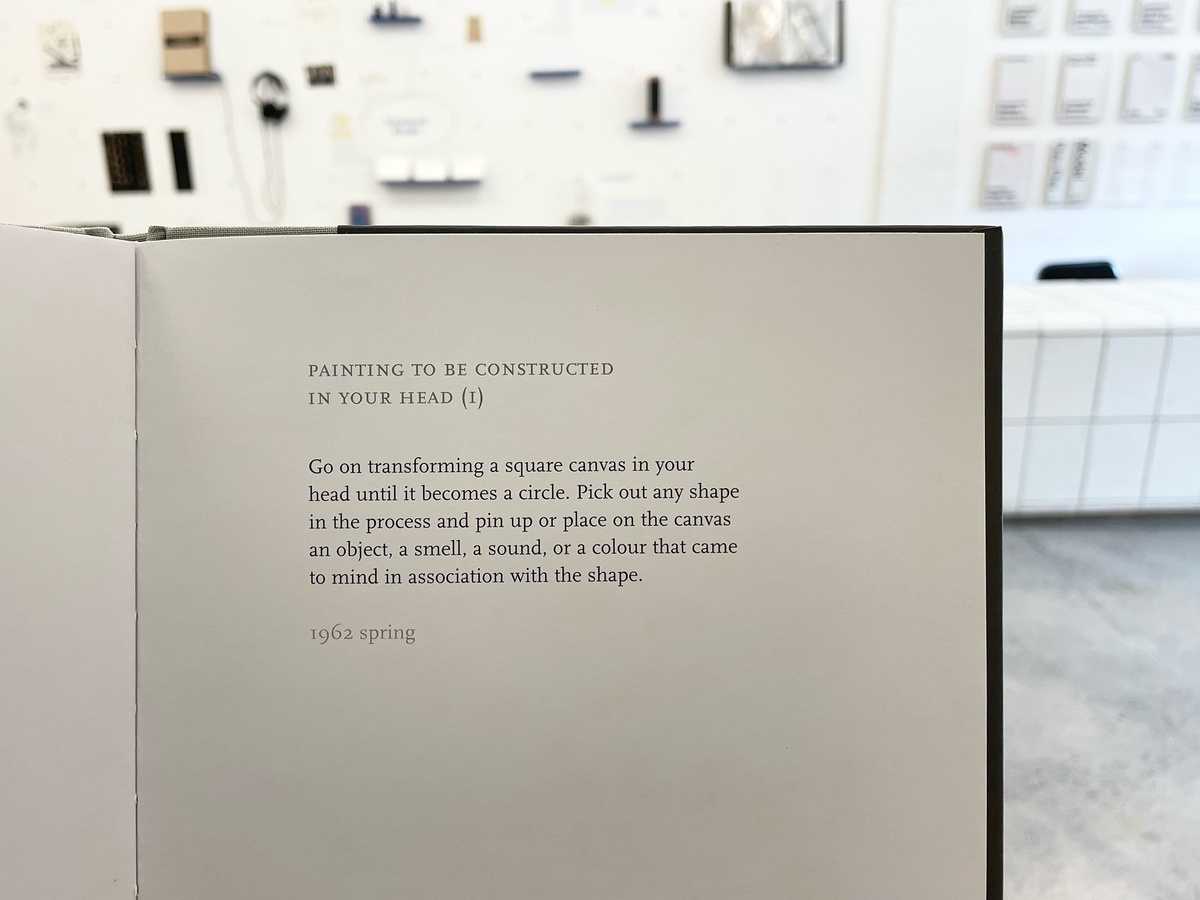

Among the art objects Yoko Ono has made, many have necessitated their own disappearance, much like Smoke Painting (1961), a canvas accompanied by the invitation to press lit cigarettes into its fibres until the fabric has all but burnt away. Drawn to the ephemeral, the incomplete and understated, those among her works that find no material expression persist instead as text, performance, film, or as koan-like instructions: “Light a match and watch till it goes out,” “draw a line until you disappear,” “make one tunafish sandwich and eat.” Some read as poetry, others are matter-of-fact. With these ‘instruction pieces’, Ono invites the viewer to perform the gesture she proposes, stepping back so that another may come forward to take her place. Even when the artist is bodily present, as in the performance Cut Piece (1965), she remains impassive; allowing her clothes to be cut away, the piece to continue on to its conclusion. Her work is coloured by this quiet contradiction: the precision of her propositions and her commitment to letting go.