Art and action

Lucienne Bestall

An introduction to instructional works. – February 3, 2025

Instructional artworks – or instruction-based artworks – are prompts or 'scores' that invite people other than the artist to realise an action, installation or composition proposed by the artist. This proposition might be written, spoken, suggested in a diagram, demonstrated, or otherwise communicated.

Being ephemeral and moveable, such works engage participants beyond established audiences and institutions. They are democratic in attitude and form, being available to others to perform or imagine, and reframing everyday occurrences and scenes as worthy of the close attention more often reserved for art objects. That instructional works tend to centre commonplace actions and materials allows one to extend the logic of such instructions to one's own life – where an hour spent sweeping or a minute's silence can assume a new significance as a performative gesture.

Like readymades or found objects, instructionals necessitate a shifting of categories. This change, however, is temporary, lasting only for the duration of the performed action. In this way, instructionals allow the work’s participating parts – people among them – to move in and out of art’s conceptual framing.

In considering such works in A4's database, I have taken some liberties, extending the genre's definition from instructions intended for the viewer to include instructions given to institutions for the installation and care of artworks. While many works are accompanied by defined procedures (how to handle them, fabricate them, or present them for exhibition), those I have chosen conceptually engage with the idea of protocols or scores, of being enacted or fulfilled by another.

Instructions for participants –

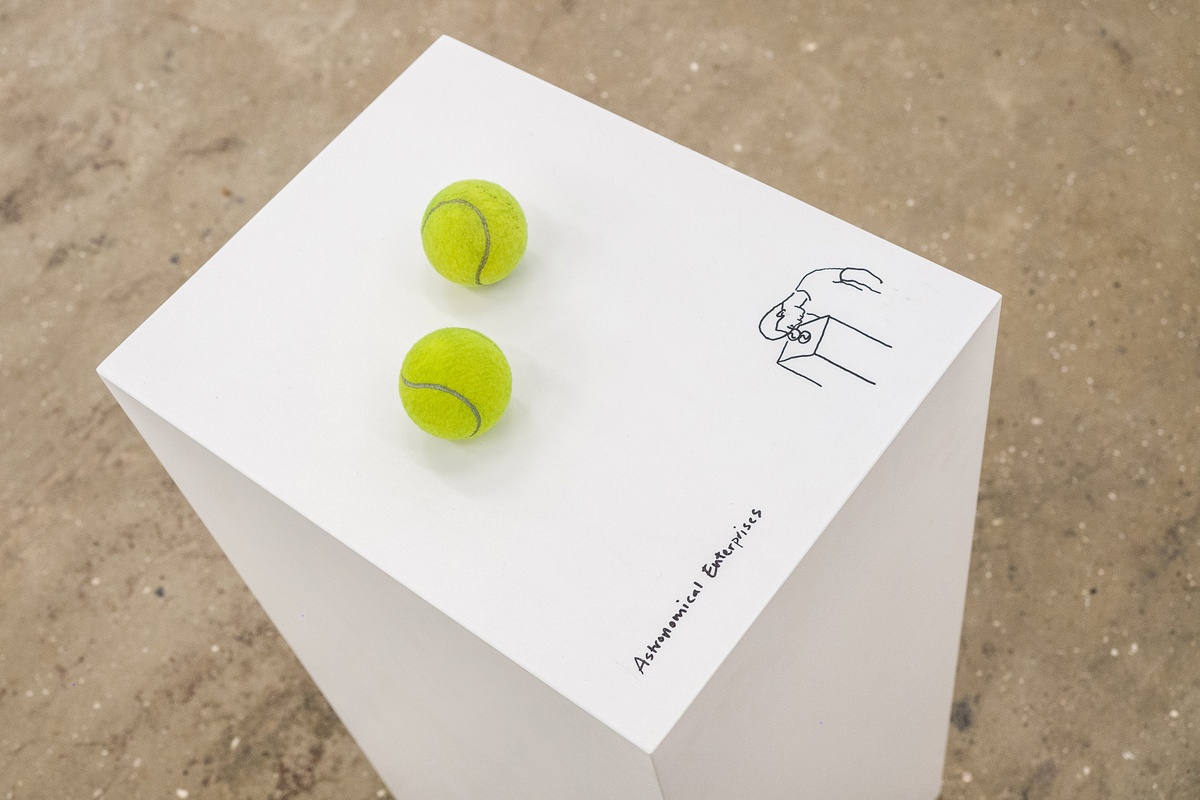

In Erwin Wurm’s many One Minute Sculptures (1988–), members of the public are invited to assume the guise of an artwork in predefined compositions centred on a series of given props (among them tennis balls, absorbent cloths, and plastic buckets). A simple sketch details the desired arrangement for each sculpture, all of which interact with a white plinth, further insisting on the participants’ new designation as ‘artwork’. Each sculpture requires that the pose persist for sixty seconds, after which the work’s constituent parts – figure, everyday objects, plinth – separate out into their respective, non-art roles.

Where Wurm makes use of line drawings, the instructions for Yoko Ono’s MEND PIECE (1966–) are conveyed by way of a poem. The Cape Town version, created by the artist in 2018, reads:

Mend with wisdomThe work invites the viewer to take a seat at a long white table and ‘mend’ broken crockery with twine, scissors, glue and adhesive tape in a gesture of renewal (of making anew) rather than perfect restoration. Engaged in this meditative labour, the artist proposes, the viewer performs a healing of symbolic significance. The resulting objects – each an assemblage of shards tenuously held together – are accumulated on the accompanying shelves. The ‘moment of art’ is at once the invitation, the action, and the fragmented objects; it is both the asking and the answer.

mend with love

mend your heart.

It will mend the earth

at the same time.

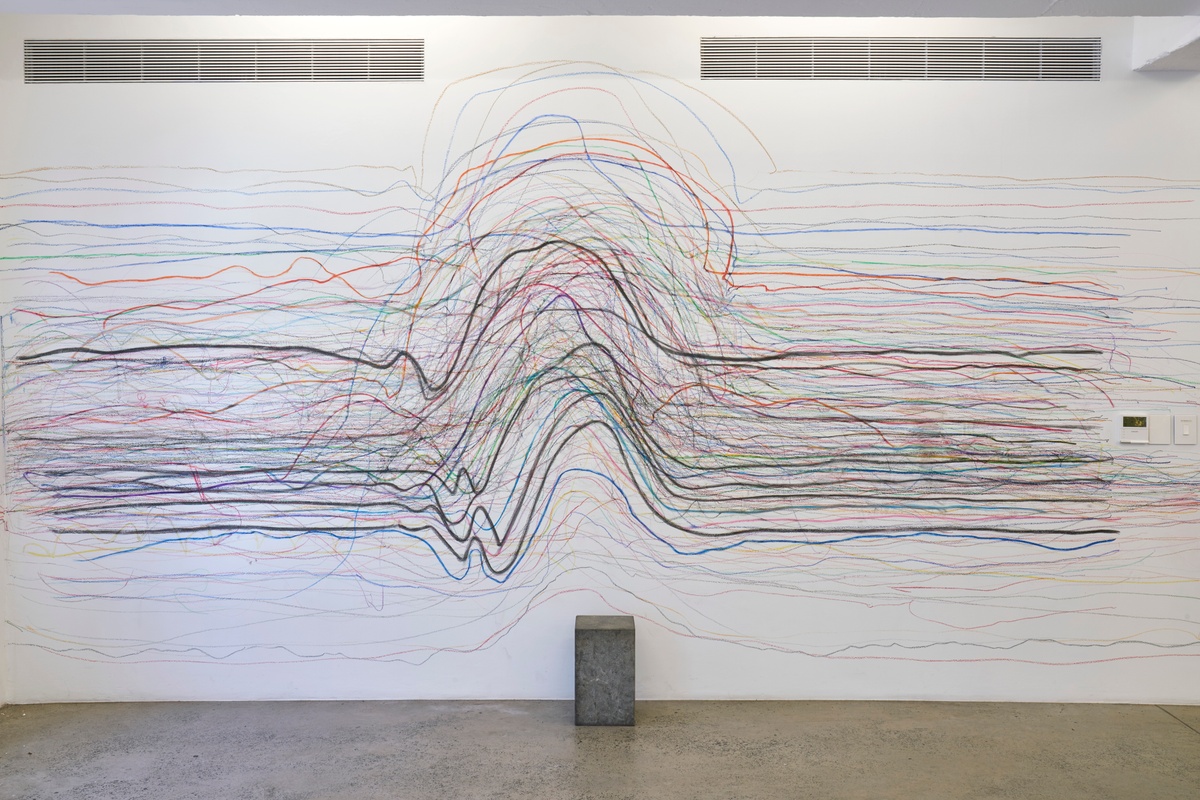

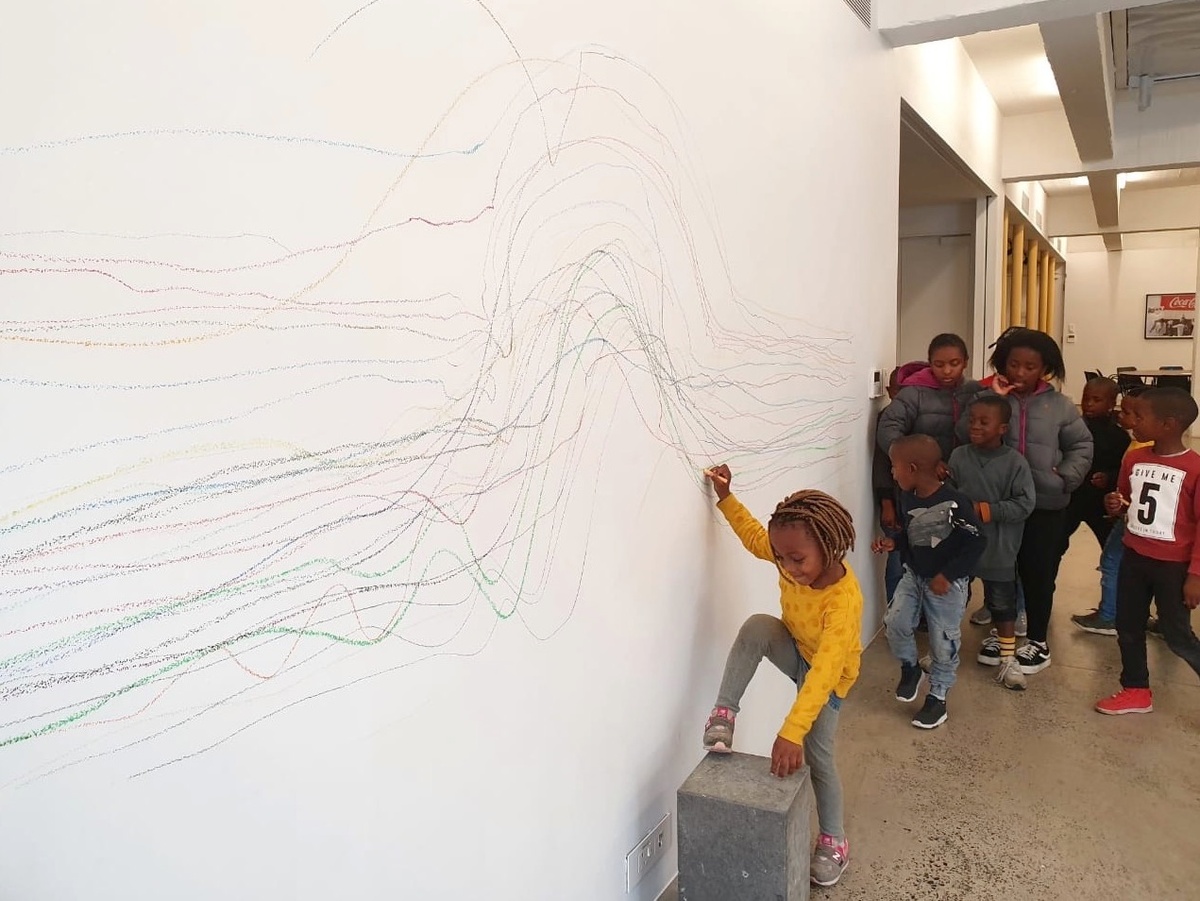

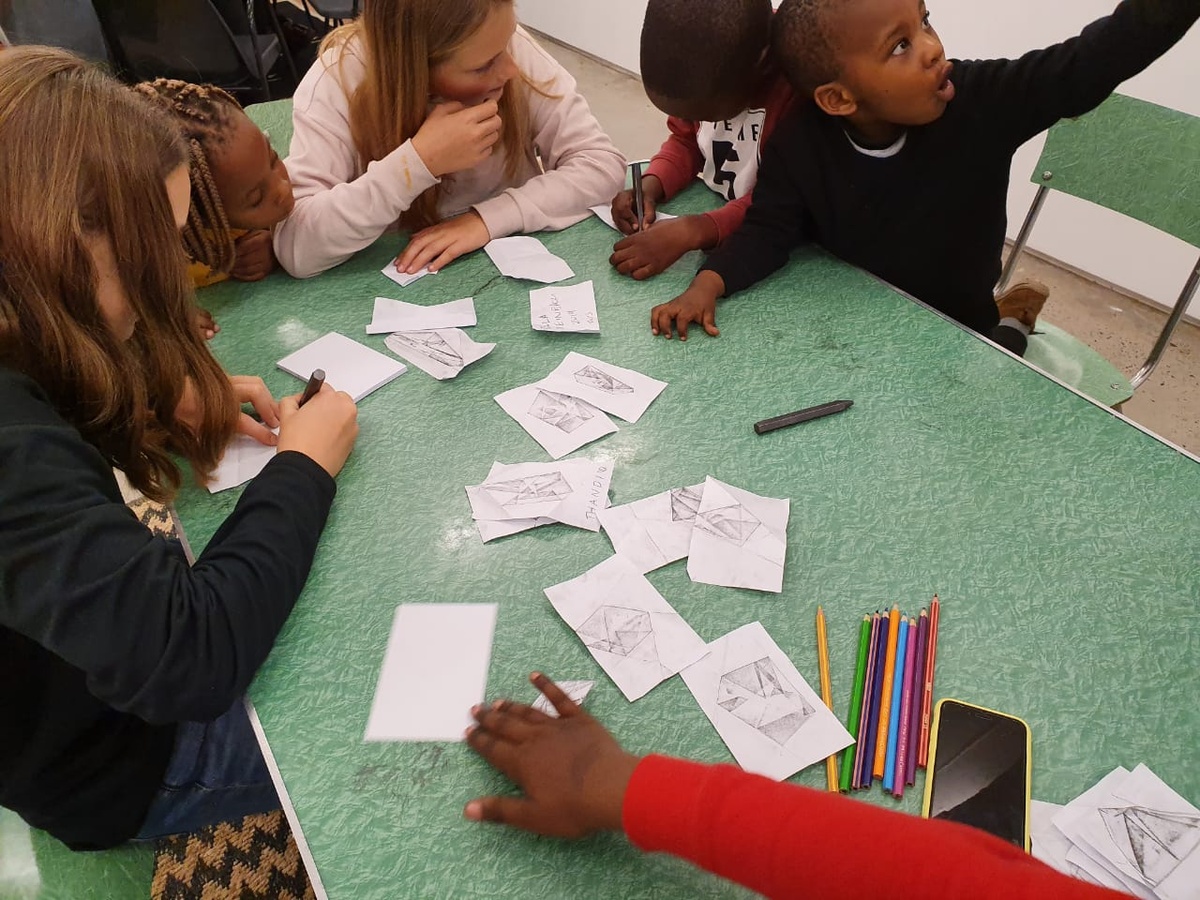

Demonstration – rather than written or drawn instruction – is primary in Christian Nerf’s drawing ‘exercises’, a series of mark-making strategies to be performed by others. These exercises are designed to be easily shared and reproduced, that anyone who has learnt the protocol might both perform the action and pass it on to others. In Working With Obstacles (2012–), participants are instructed to navigate a given obstacle while simultaneously drawing a line in crayon directly on the wall to create a collaborative abstract composition.

The 2019 iteration of Nerf's Working With Obstacles, as well as another such exercise, Teaching Teachers, took place during his Summer School for children at A4. What remained after the young participants had gone were drawings of uncertain category – artwork or artwork’s trace?

Instructions for installation –

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense, a ‘library’ of bricks that gestures to the politics of knowledge production and censorship, was produced at A4 following instructions provided by the artist, which engaged an assigned maker in unseen repetitive labour, priming and painting building bricks to be set into purpose-built shelving. That the work is fabricated anew wherever it is shown gstures to the discrete literary histories of the settings in which it is made. Following its exhibition, Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense is dismantled, its parts returned to their respective functions (bookshelves, bricks) or otherwise dispersed – or preserved for future expressions of Wa Lehulere’s library.

Similarly to Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense, many of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ works exist as instructions to be realised by exhibiting institutions. In addition to straightforward matters of installation, the instructions for "Untitled" (Orpheus, Twice) (1991) offer conceptual parameters that lean towards the metaphysical:

The Work exists regardless of whether it is physically manifest.Each authorised manifestation of the Work is the Work and should only be referred to as "the Work."The material used to manifest the Work that remains after the close of the exhibition is no longer considered the Work.

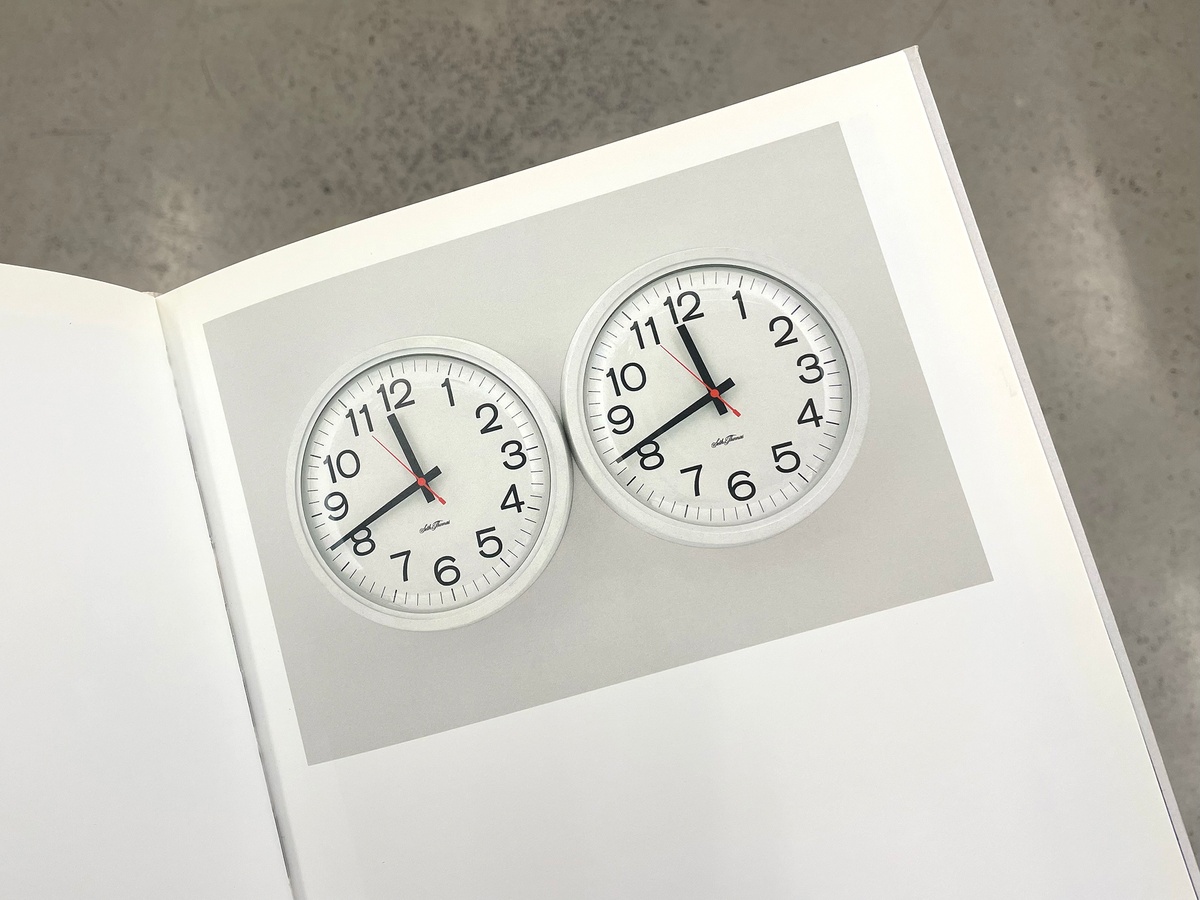

Where "Untitled" (Orpheus, Twice) can appear simultaneously in different spaces, several works by the same artist, while also 'made' again on each installation, are accompanied by a guiding rule: the work may only exist in one place at any given time.Such is "Untitled" (Perfect Lovers) (1991), which comprises two identical store-bought clocks set side-by-side, ideally installed above head height and against an optional blue wall. The limiting of the work to a single manifestation in time and space affirms its aura as a singular object, however reproducible its form.

Much care is given to the wording of the instructions that accompany each of Gonzalez-Torres' artworks. In addition to "fostering and facilitating individuals' direct experiences with the work," the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation's custodianship of the artist's legacy includes the ongoing development of 'core tenets' that provide "language around the nature and structure of works." These in-progress documents are continuously revised to best reflect Gonzalez-Torres's intentions, highlighting the subtle variations between discrete yet similar artworks.

Included in the materials list for Kapwani Kiwanga's Ground (2012) is 'protocol'. The work, composed of photographic printouts of amateur images found on the web, asks that the exhibiting institution connect the images in a prescribed sequence to "create an uninterrupted line of lightning from the ceiling to ground." There is no invitation to interpretation here – the only variable being the height of the wall on which the work is installed, which determines the length of the forking flash.

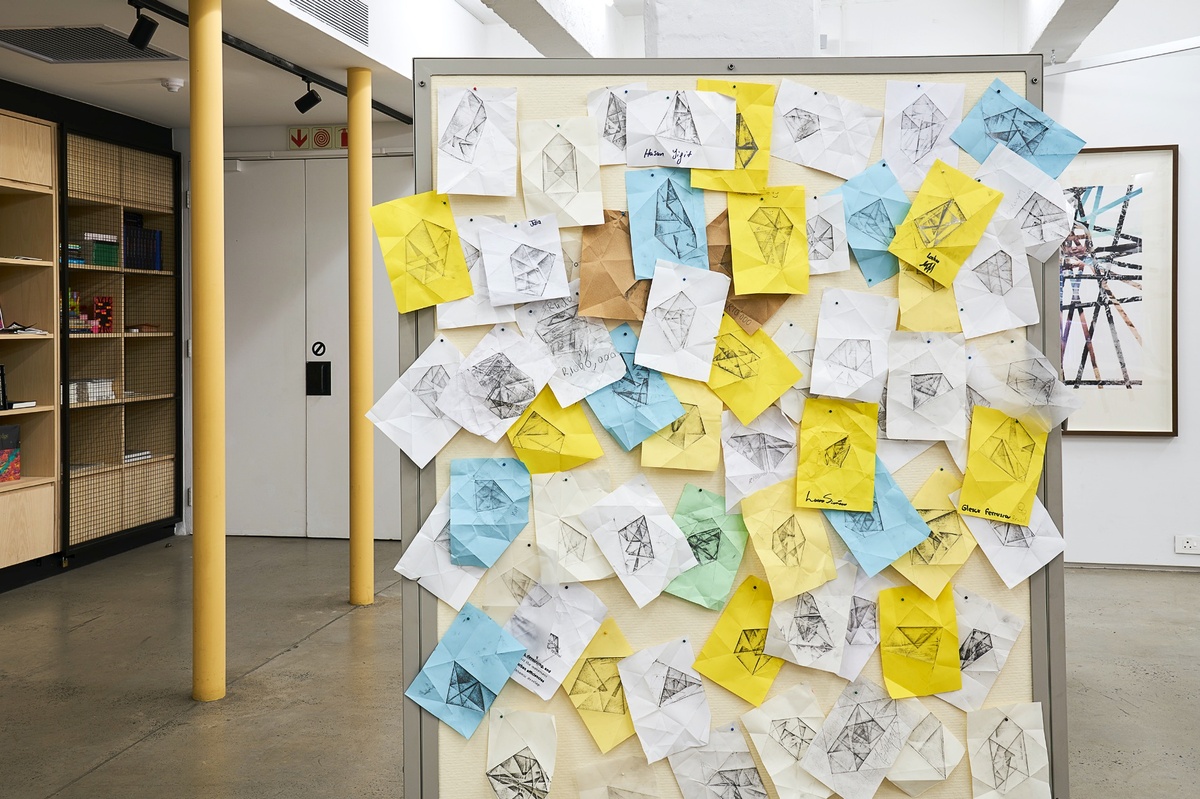

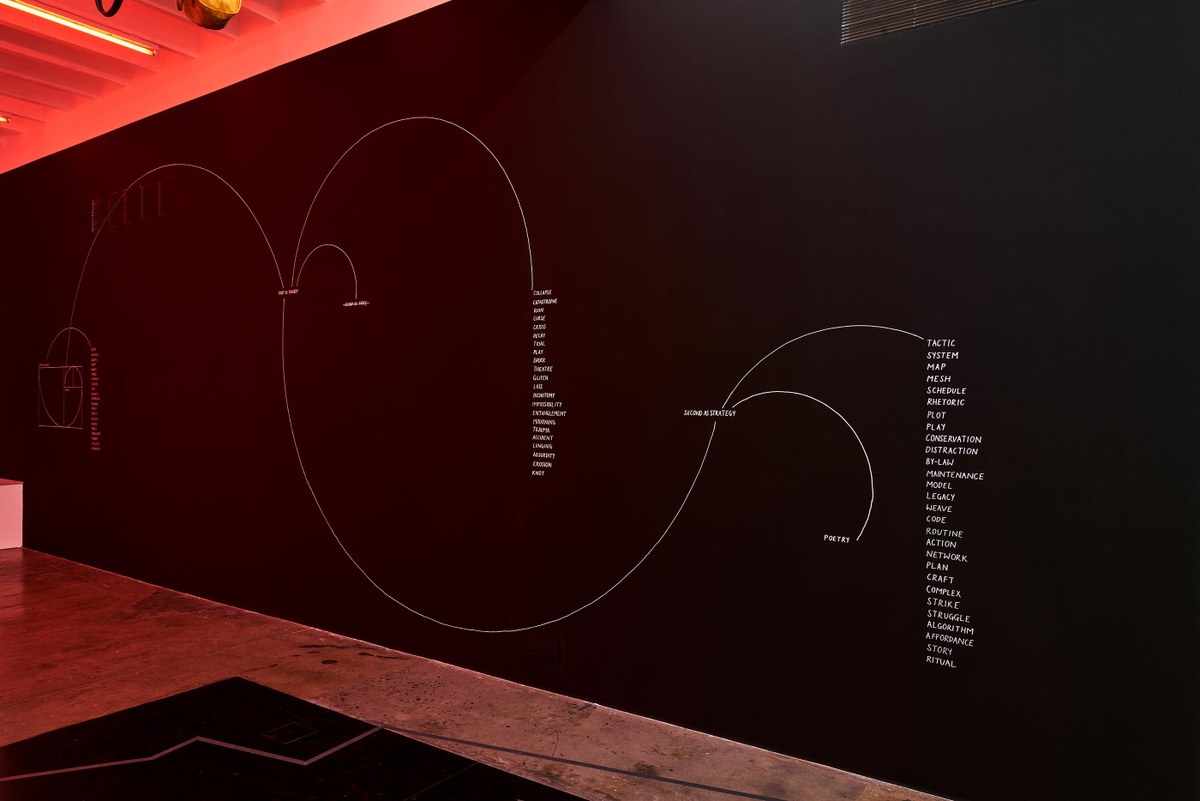

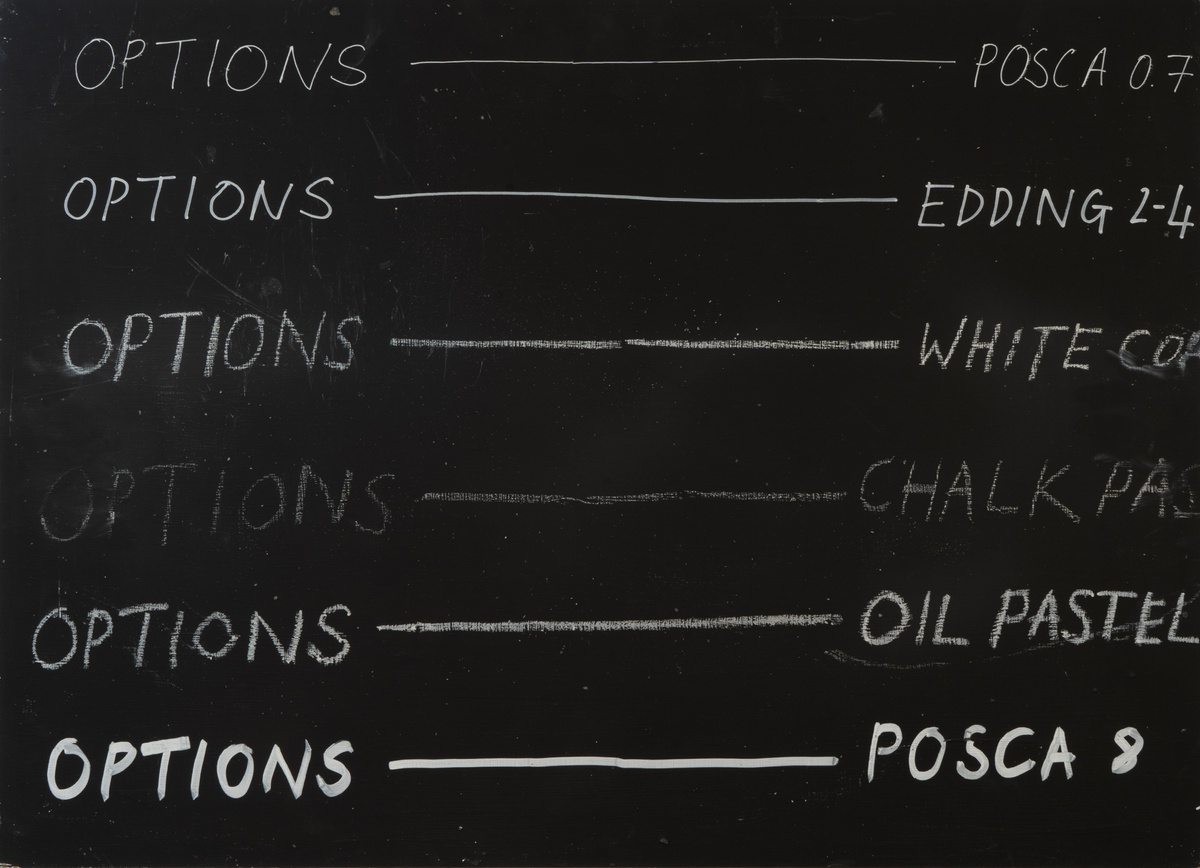

Other instructional works are more open-ended. Iteration and deviation are central to Nolan Oswald Dennis’ Options (2018), a large-scale formulaic drawing that invites a technician to interpret its instructions on each installation. “This procedural function allows someone else to engage with [the artwork], not by reproducing it but by producing it with space for transformation,” the artist says. Being infinitely generative, Options considers change within constraint; variability within constancy. The work’s complexity exists in this space of transmission between protocol and performance. What language will the technician choose? What measurement will they begin with? How will the meaning and scale shift? The version installed at A4 for Customs was produced by artist Bella Knemeyer.

Instructions for care and maintenance –

Some works demand a durational performance, their instructions extending beyond installation. Such is Nolan Oswald Dennis’ garden for fanon (2021), which necessitated that a member of the A4 team read aloud from Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961) to a community of earthworms each day for three months. Reaching the end of a given page, the teammate tore it from its binding and placed it in a glass globe for the worms to slowly process into compost. As a complex bioactive system, the work requires the exhibiting institution to enact this procedural care, tending to the worms that they can tend to their task: refiguring history’s complexities as loamy substrate. One might say that the work’s instructions are performed both by the institution and by the worms, who play their part with unflagging commitment.

Here it is perhaps useful to note those instructional works that tend towards care's antonym. Two participatory performances come to mind – Yoko Ono's Cut Piece (1964) and Marina Abramović's Rhythm 0 (1974), both of which invited the audience to interact with the artists’ still, impassive bodies and a selection of props (scissors in the first instance, and everything from a rose to a gun in the second). That the audiences more often assumed an aggressive cruelty towards the artists was not predetermined. There was no invitation to violence, only an imagined inference. Writing of a 1966 performance in London, Ono said: "People went on cutting the parts they do not like of me. Finally, there was only the stone remained of me that was in me, but they were still not satisfied and wanted to know what it’s like in the stone."

Instructions as subject –

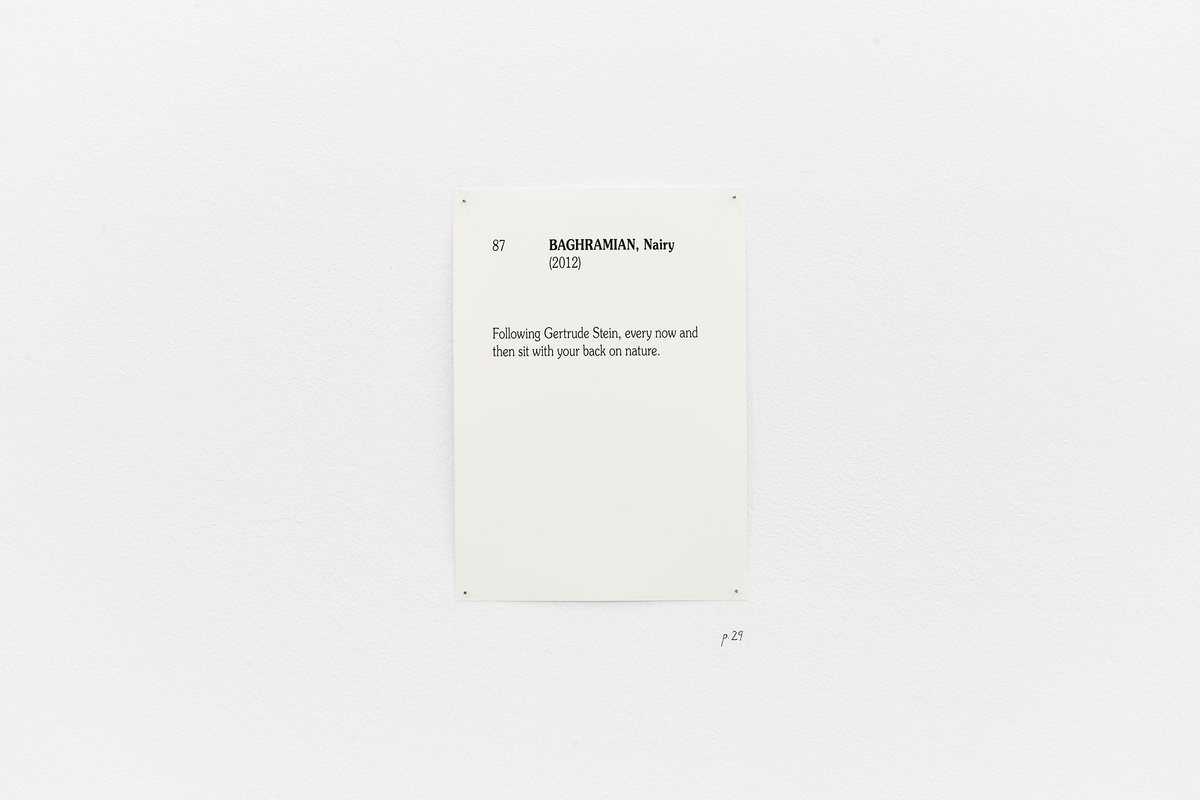

Nairy Baghramian’s word-based instructional was first included in 'do it', an ongoing, iterative project by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist that has been exhibited globally – and almost continuously – since launching in May 2013. The exhibitions and publications that comprise the project follow a simple formula: invited artists submit written scores to be performed by participants. “Like all art by instruction,” art philosopher Bruce Altshuler writes, “'do it' is essentially open, allowing for a range of realisations according to the interpretations, choices, constraints of those who follow the directions. Like the works composing it, 'do it' is a multiple of potentially unlimited variety and number,” In 'do it', the instructions are the thing, each an artwork in and of itself – regardless of when, how, or if they are ever realised.

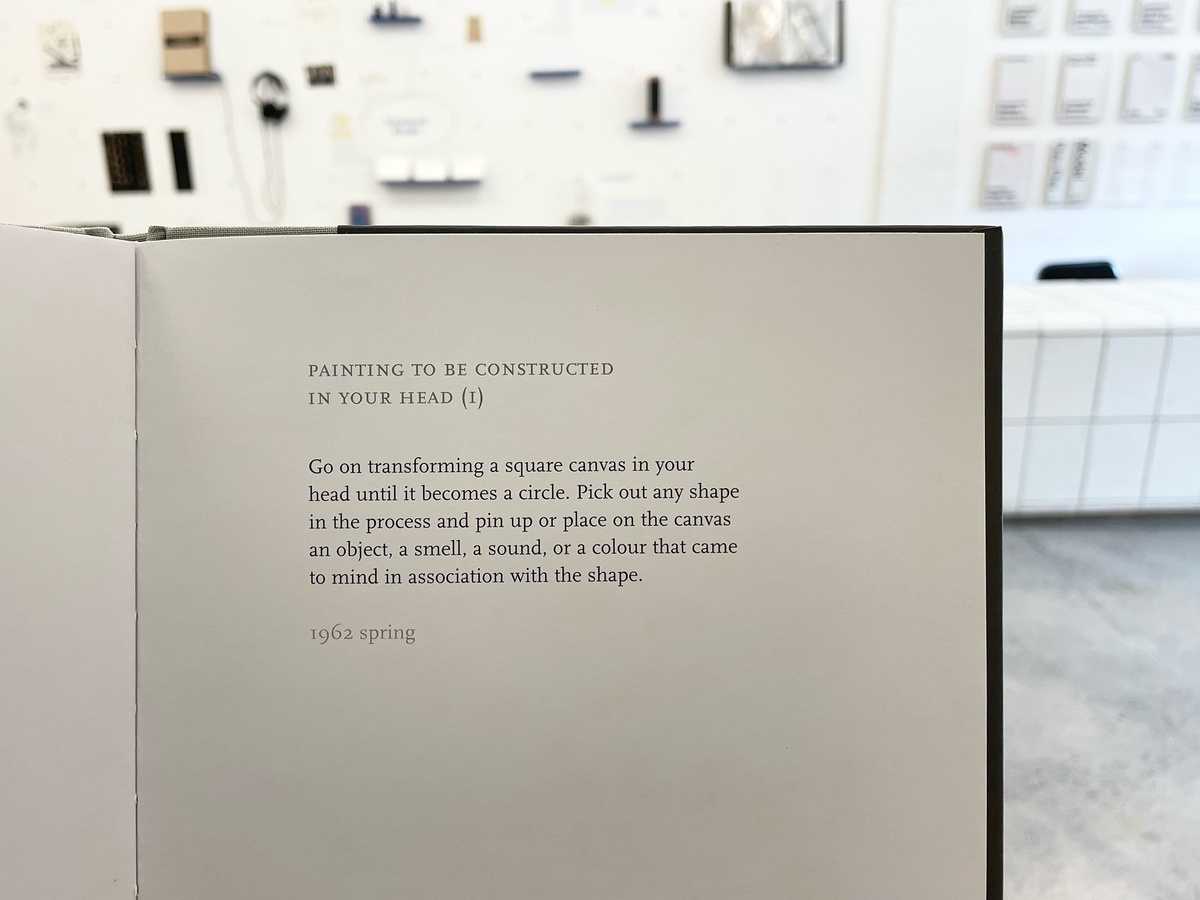

The conceptual frame of Obrist’s ‘do it’ finds its genesis in Fluxus, a loosely connected international movement of artists in the 1960s and 70s of which Yoko Ono has become emblematic. Her book Grapefruit (1964) is often cited in relation to instructional art, with its collated poems and text-based scores that are as much conceptual propositions as gestures to be realised. Ono's instruction-based works are by no means unique, being a strategy deployed by many other Fluxus artists, all greatly influenced by the avant-garde composer John Cage (among others) and Marcel Duchamp before him. As Altshuler writes, “the modern tactic of removing the execution from the hand of the artist appears in 1919 when Duchamp sent instructions from Argentina for his sister Suzanne and Jean Crotti to make his gift for their April marriage. To create the oddly named wedding present, Unhappy Ready-Made, the couple was told to hang a geometry text on their balcony so that wind could ‘go through the book [and] choose its own problems…’”

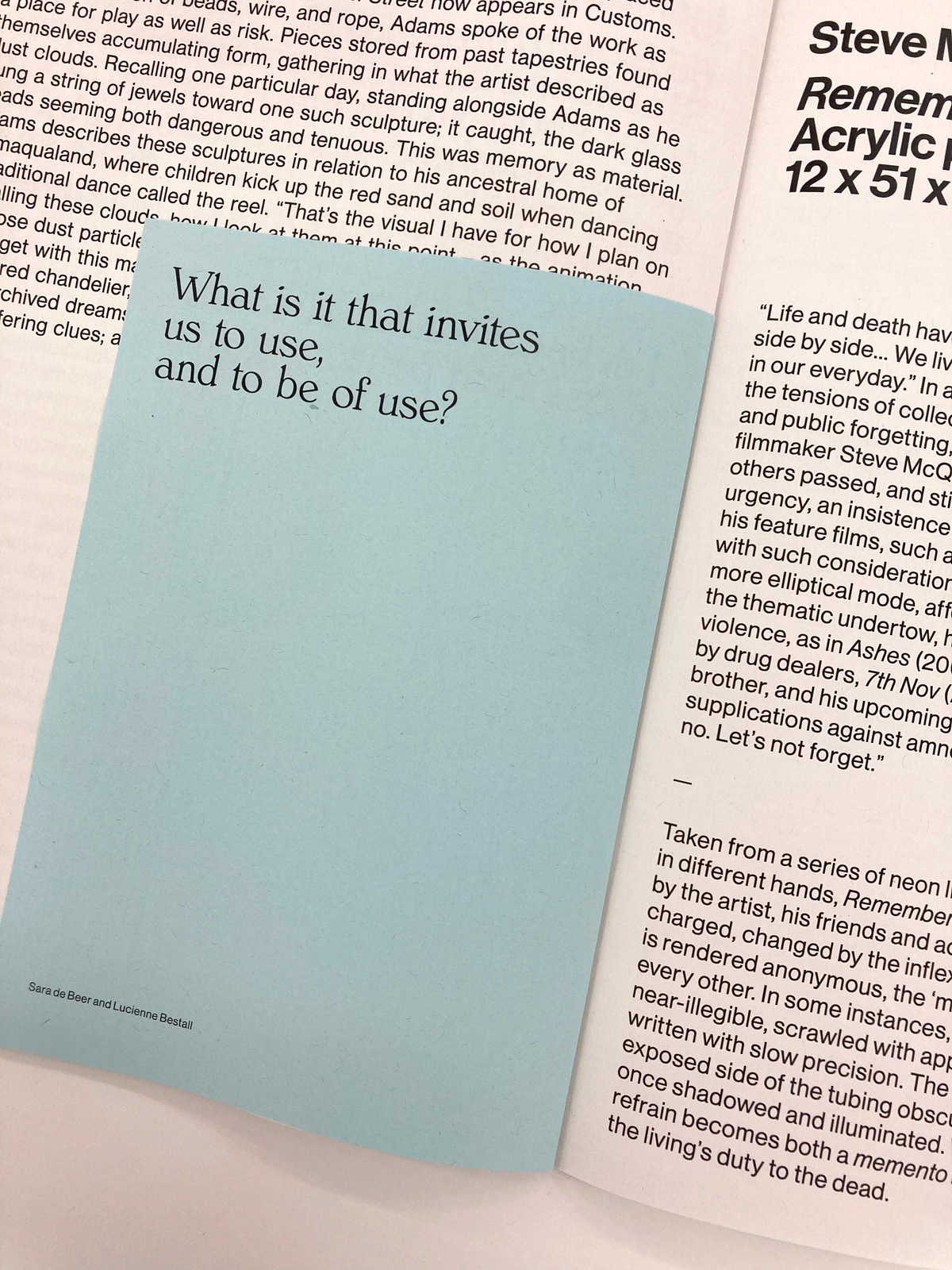

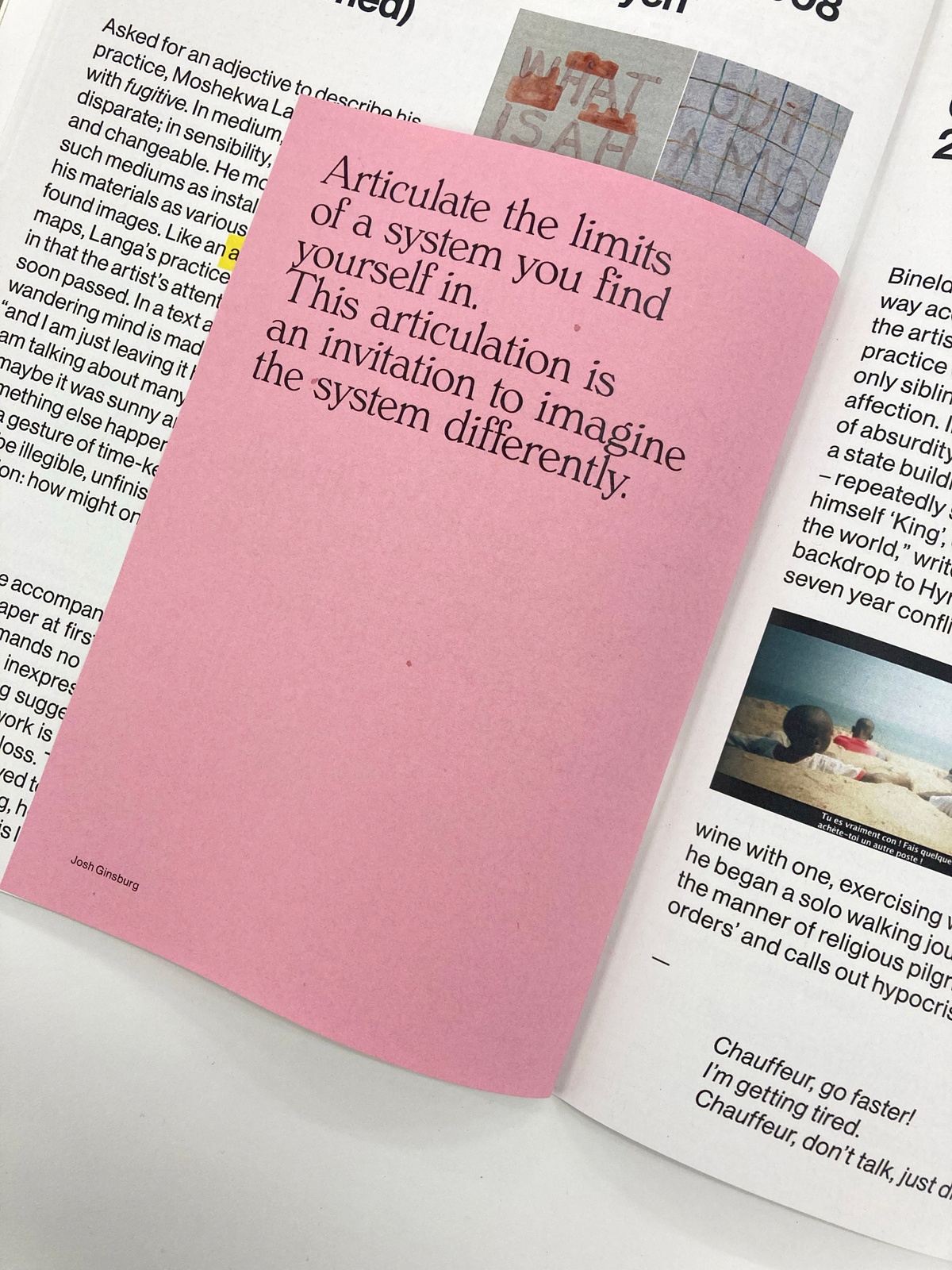

Reflecting on instruction-based works, A4's team included prompts for thinking about art and action in the Customs wayfinder following a series of conversations with invited practitioners. Curated by Sumayya Vally and Josh Ginsburg, the exhibition asked after ritual, inheritance, participation, and maintenance – all ideas that intersect with the instructional form. The wayfinder's inserts offered ways with which to think through the exhibition's thematic considerations.

At A4, we often ask: "How do ideas and artworks travel?" The question extends beyond the expected mechanisms (like the intricacies of international shipping) towards more idealistic aims – how can artmaking and -thinking be shared widely and effectively? In considering how A4 can promote greener, more equitable and accessible programming, instructional artworks offer a model. Words, a few everyday items, a protocol for installation, even worms – such works prove remarkably light-footed and limber.

Instructionals communicate with brilliant clarity that 'art' is not a rare quality restricted to discrete cultural objects but rather a framework for thinking about and inhabiting the world – a temporary designation or attitude that can be assumed with the slightest shift in attention and purpose.