Félix González-Torres

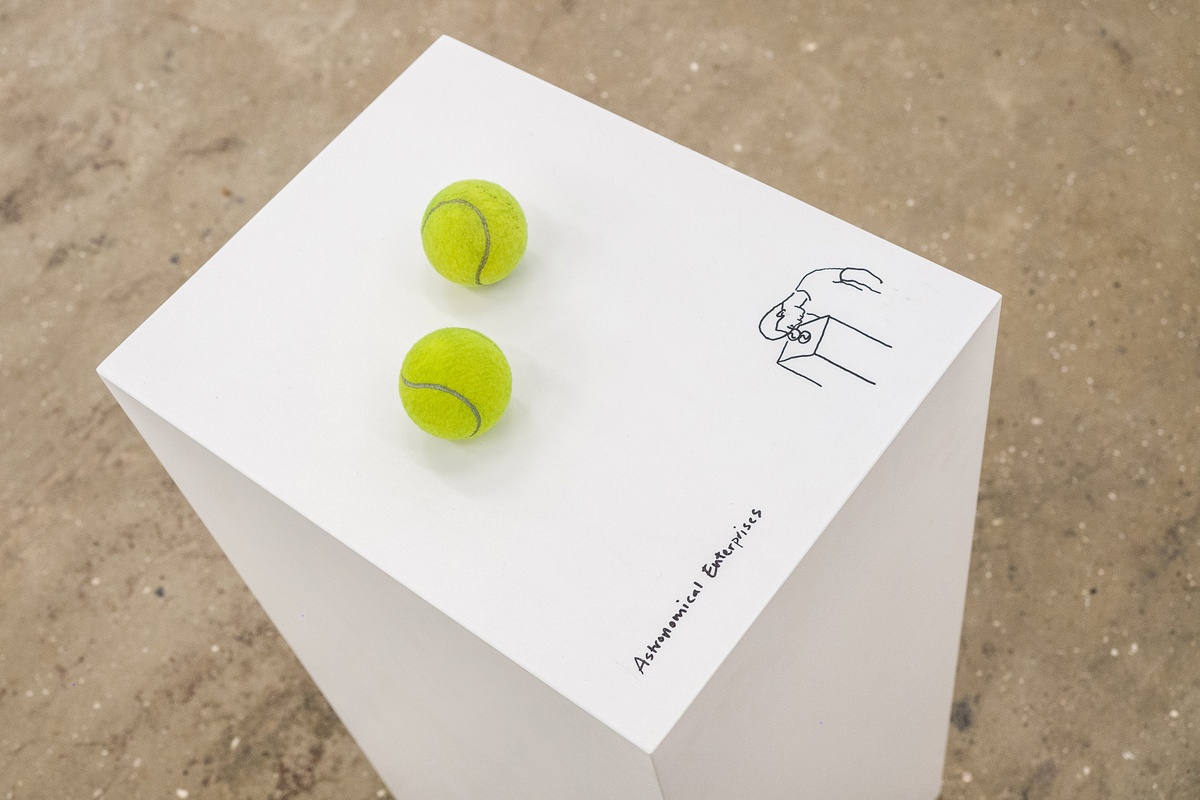

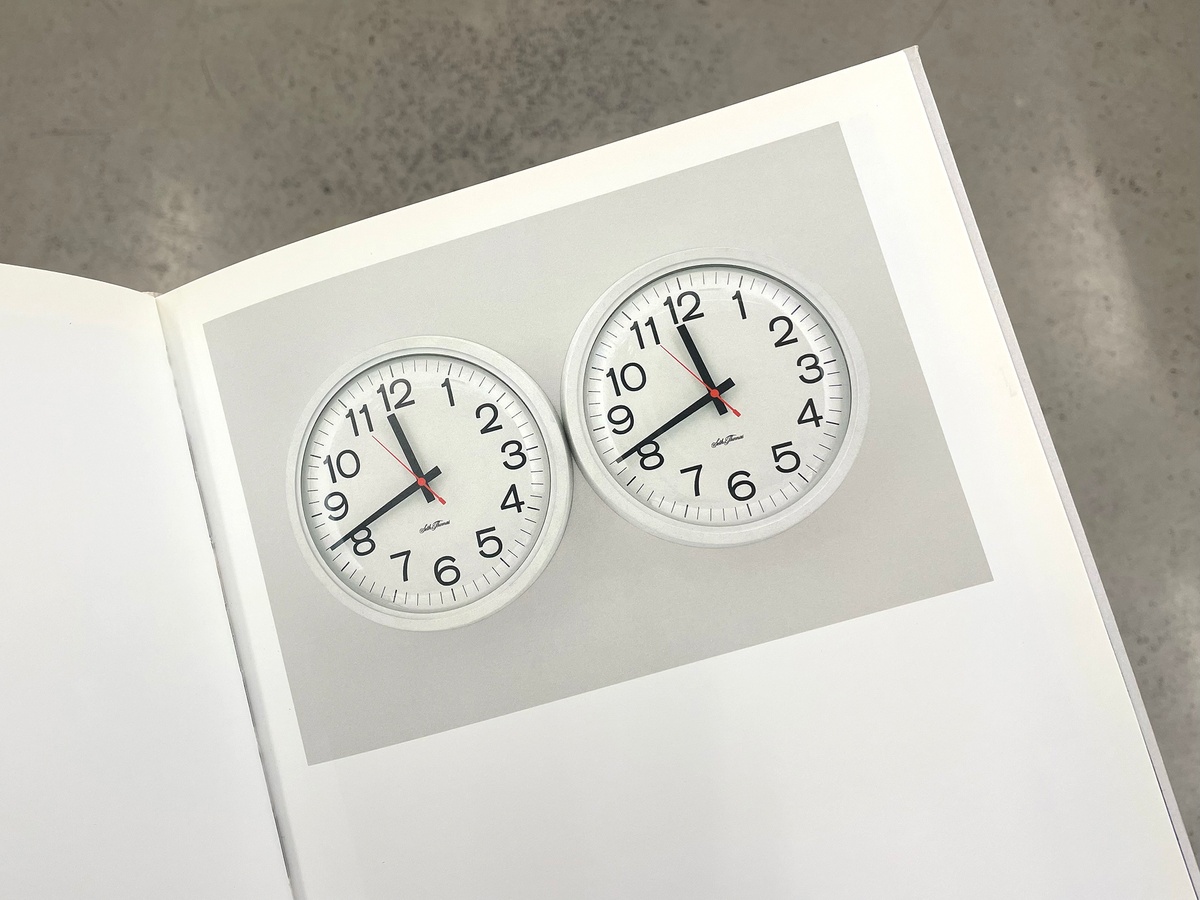

Transforming everyday objects into poignant metaphors, Félix González-Torres addresses themes of love and loss, sexuality and sickness in works of material and formal simplicity. His practice pursued articulations of life and its fragility; the inevitability of the end. Initially trained as a photographer, González-Torres’ installation works extend a striking pictorial clarity. Often pairing identical objects – two clocks on a wall, two circles on a page, the two mirrors that comprise “Untitled” (Orpheus, Twice) – his double forms gesture to two lovers and their sharing of image and consciousness; the ideal of perfect synchronicity with another. Following the death of his life partner, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1991, these twinned works assume a shade of mourning. “Untitled” (Orpheus, Twice) recalls in its title the myth of the Greek prophet, who descended to the underworld to find his lost lover and return her to the world of the living. Thwarted in his attempts, he was later killed by followers of Dionysis, who – in some retellings – had tired of hearing his mournful songs. The work holds a particular resonance in relation to González-Torres: in 1996, the artist followed his partner in death.

–

The following are excerpts from various conversations with the practitioners Kader Attia (K.A.); Tarik Yikdrim (T.Y.); and Jo Ractliffe (J.R.); Gian Maria Tosatti (G.M.T.) and Josh Ginsburg (J.G.) in preparation for The Future Is Behind Us, 29 November, 2022.

J.G. Opposite (Untitled) Ghardhaia is installed "Untitled" (Orpheus, Twice) by Félix González-Torres. The work, two mirrors side by side, draws the other works that are in the room inside of it. There is the dialogue between the viewer and the artwork, and between the artworks in the room.

K.A. The mirror is a camera in and of itself, moving around and pulling whatever it reflects into it.

J.G. Two mirrors stand alongside one another, representative of himself, his lover, the infinity of their love, the affinity of their love.

11 November, 2022

T.Y. In Sufism, it is said that reality is like a mirror. When you look at a mirror, you see yourself. But, there's an illusion. The mirror is behind you, and it's dark. You don't see the mirror but the reflection, which is real. The object itself doesn't reveal itself to you – it remains dark, unknown, towards the back.

Think of yourself as a mirror. What remains at the back, in the dark part? What appears towards the front of the glass? Which is more real?

1 December, 2022

J.G. Tarik said something very curious about mirrors – that when you look into a mirror you never see the mirror; the mirror is not what you are looking at. You see what the mirror shows you, you cannot see its dark layer – but it is precisely the dark layer that allows you to see the reflection.

J.R. I think it’s similar to an eye. Though sometimes you can see – however slightly – the split in the mirror; the double surface.

8 December, 2022

G.M.T. We don’t need mirrors to see what is visible. We can see the largest part of our body without a mirror. The other parts of the body that we can't see, we can ‘see’ with our other senses: we can touch them. I can see everything that is visible, without a mirror.

What to see with the mirror is what is invisible. What I cannot see without the mirror is the veil of sadness or happiness. The mirror can show us the soul; show us what is invisible.

Art is a mirror. This can change related to context, because the mirror is not reflecting only the person who stands in front of it, else the artist would be only a technician. The mirror must be placed somewhere, in a context.

b.1957, Guáimaro; d.1996, Miami