Kemang Wa Lehulere

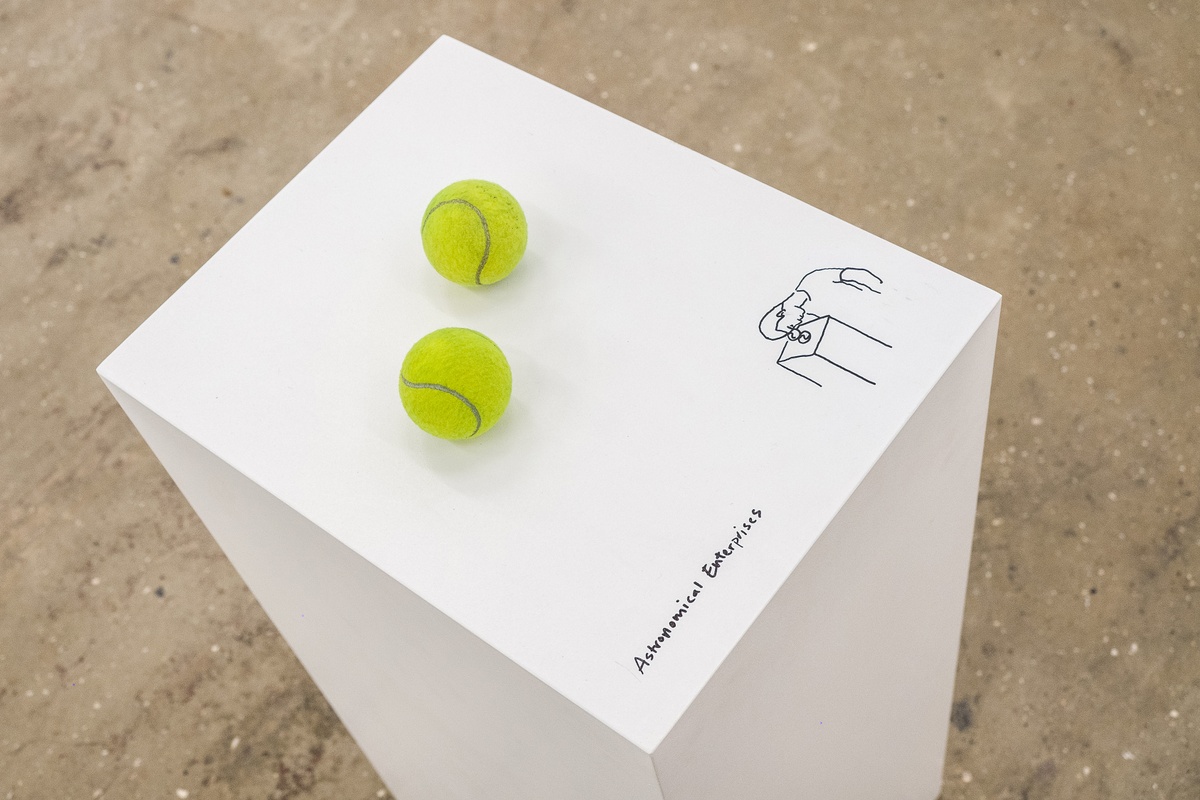

Sean O’Toole in A Model Brick: A Literary History of the Brick in Johannesburg frames the brick as “an object capable of reciting itself – of being this, a metaphor for suspended outrage, but also that, a pilfered building block, a stony nothing.” Composed of 365 bricks, one for each day of the year, Kemang Wa Lehulere’s Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense is a library. Each of the brick-books is painted with blackboard paint. For this installation of the work, the shelves and surrounding walls have been painted ‘library’ green, reminiscent of classroom boards. Collected together on these shelves, the bricks appear to be wrapped, jacketed, uniform; a set of dusty objects unboxed from history's attic. The work's title is borrowed from a 1980 song by the Nigerian singer Fela Kuti – a protest anthem against the colonially imposed Western education system’s failing of African students. The brick itself can be both used to build or to dismantle, “alluding to the harshness of the state, and at the same time, used in protest as a weapon. There’s an ambiguous materiality,” says Wa Lehulere, gesturing to the political potency of literature through the formal qualities of the brick.

–

The following is an excerpt from a conversation between Kemang Wa Lehulere (K.W.L.) and Sara de Beer (S.D.B.) in preparation for The Future Is Behind Us, 13 December 2022.

S.D.B. What is your relationship to the future?

K.W.L. The future is a desire that never arrives. History is something that lives in the present. Everything that exists was created previously. When something is produced, it becomes present and past at the same time.

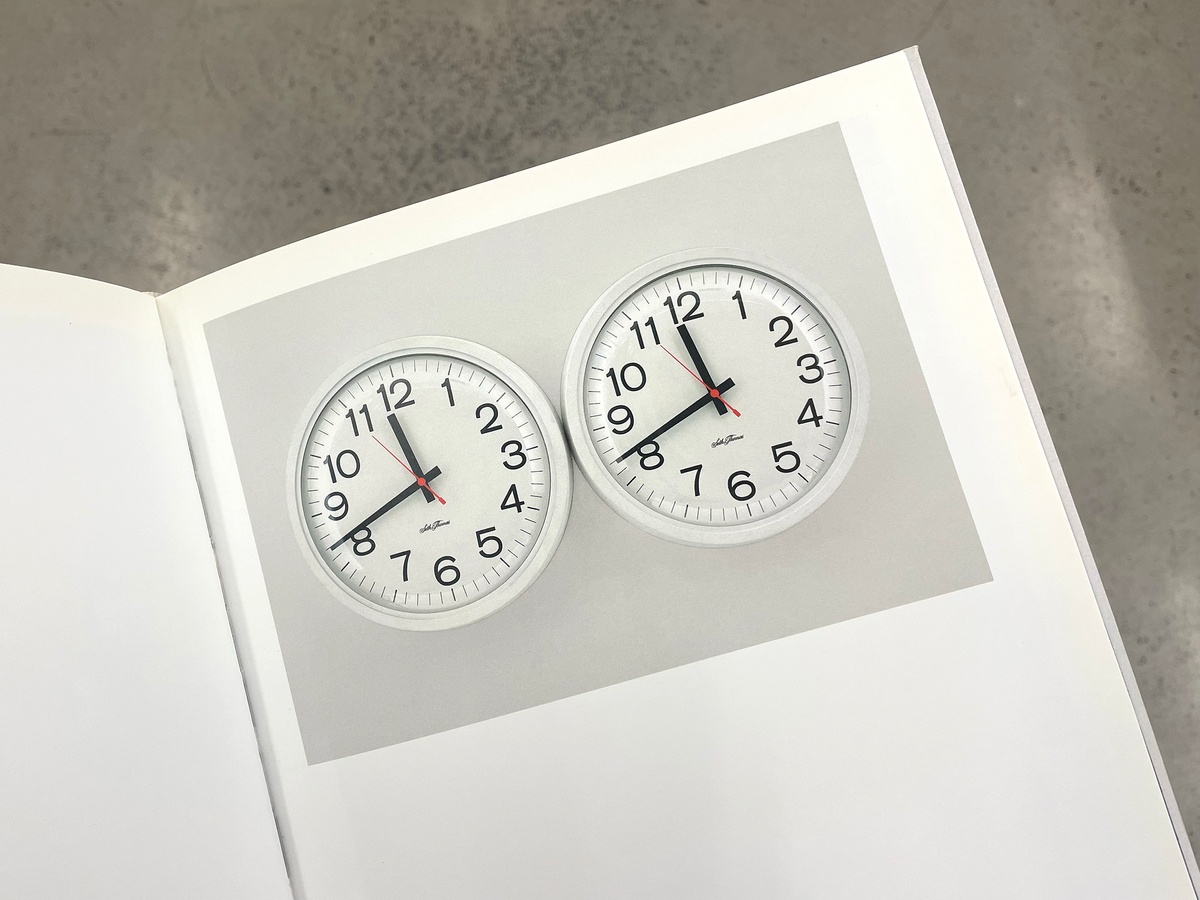

I’ve spoken before in other interviews about time being elastic. When one moves away from non-linear time, it becomes possible to time travel in an artwork, accessing the future, present and past at the same time.

S.D.B. How did this work come about in Venice for The Future Generation Art Prize?

K.W.L. They discovered a closet in the space that I was allocated in Venice, within the Palazzo. I had no existing work that could fit into that closet, but I began thinking about the various meanings of being hidden, being ‘closeted’, and how to make a work that references something that is to be stashed away – for instance, banned books. There could be no changes to the historical building in which the work was installed in Venice. Here, the green is the green of the chalkboard in the classroom of a child. It is ‘library green’.

b.1984, Cape Town

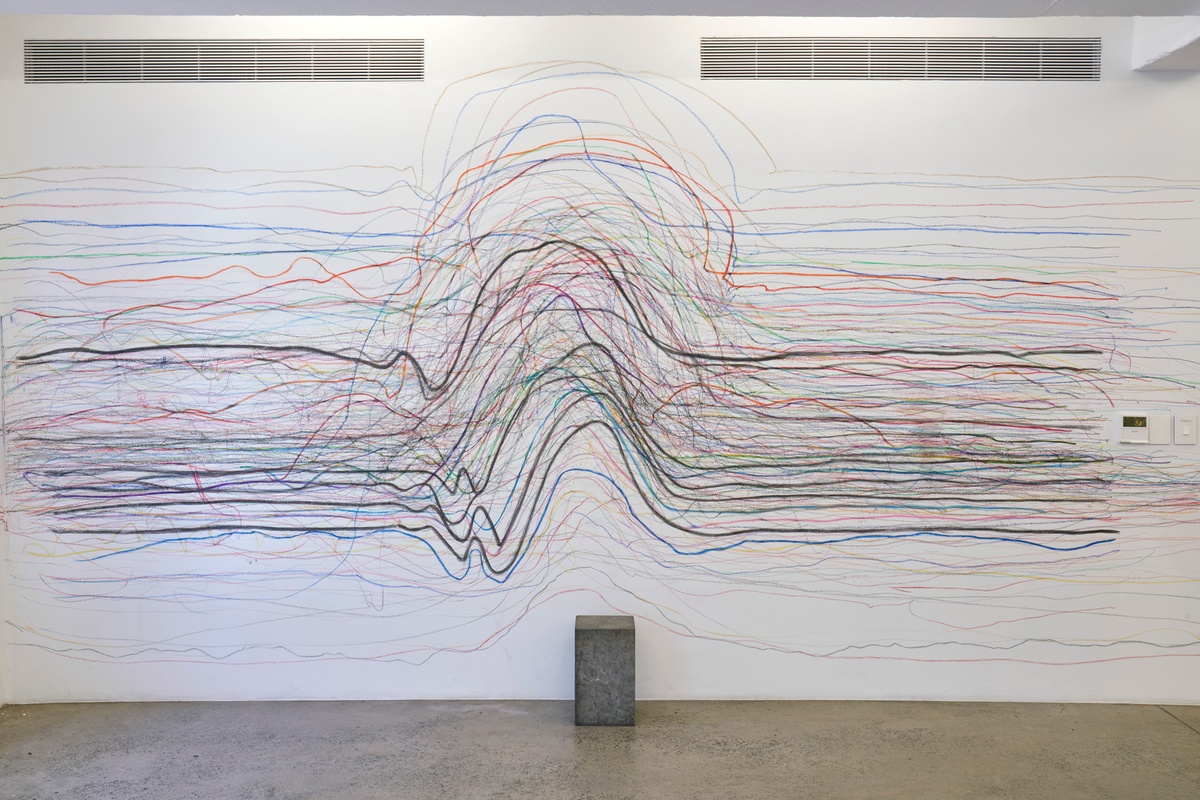

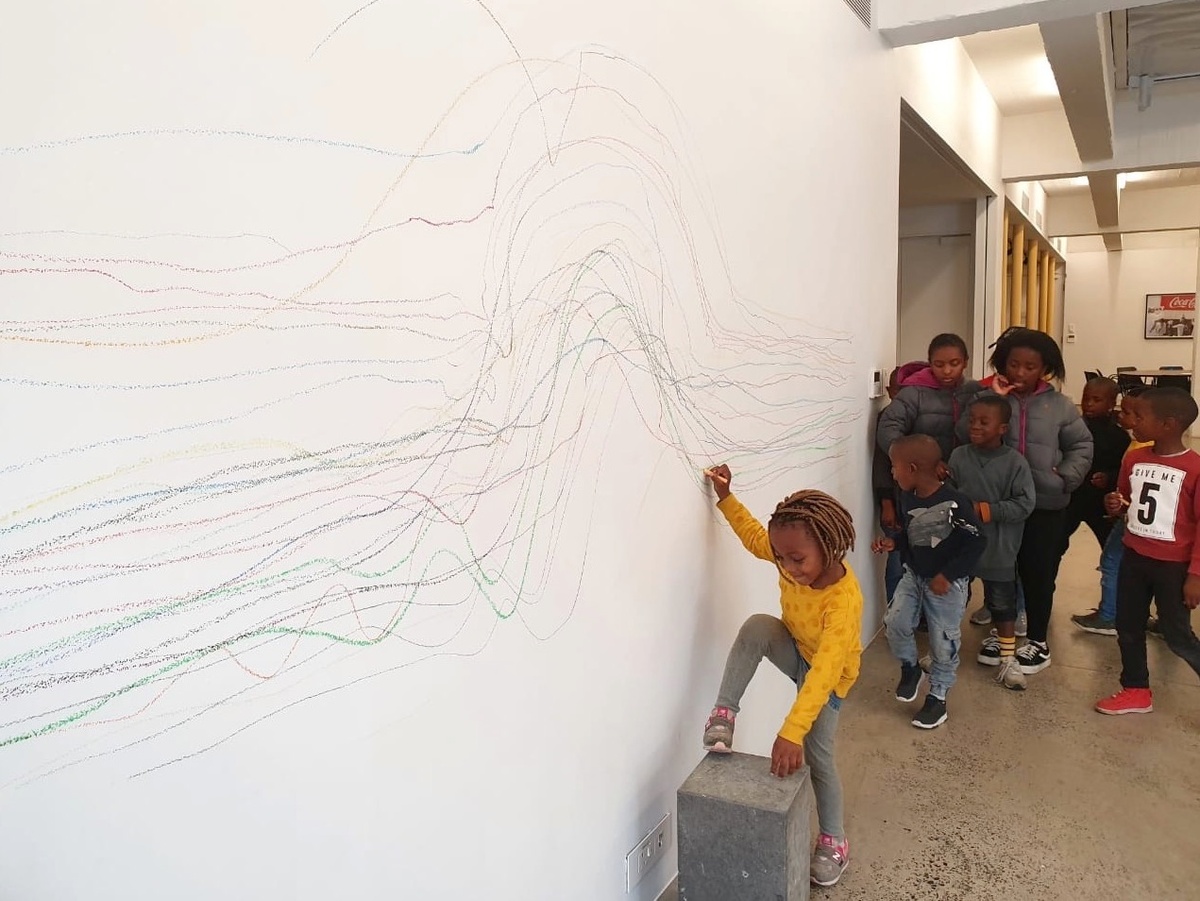

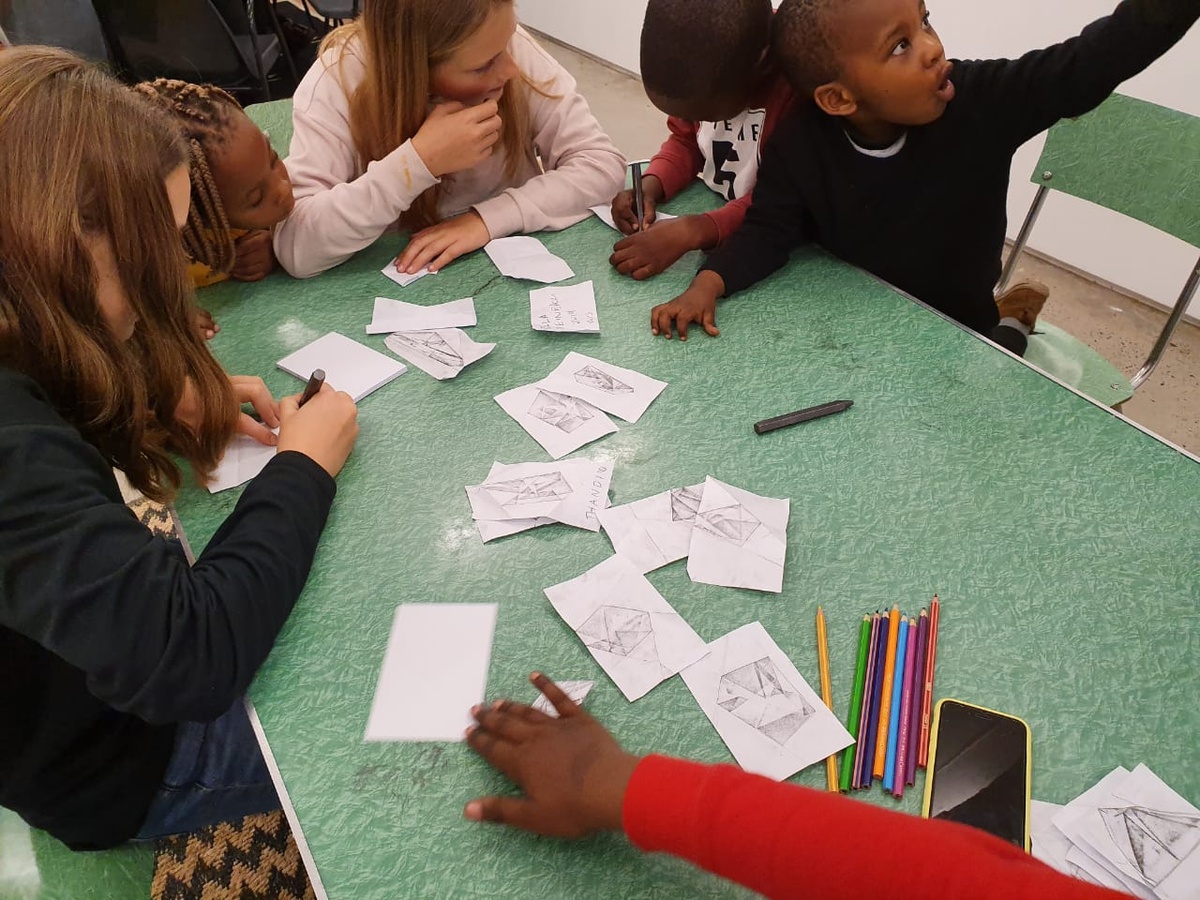

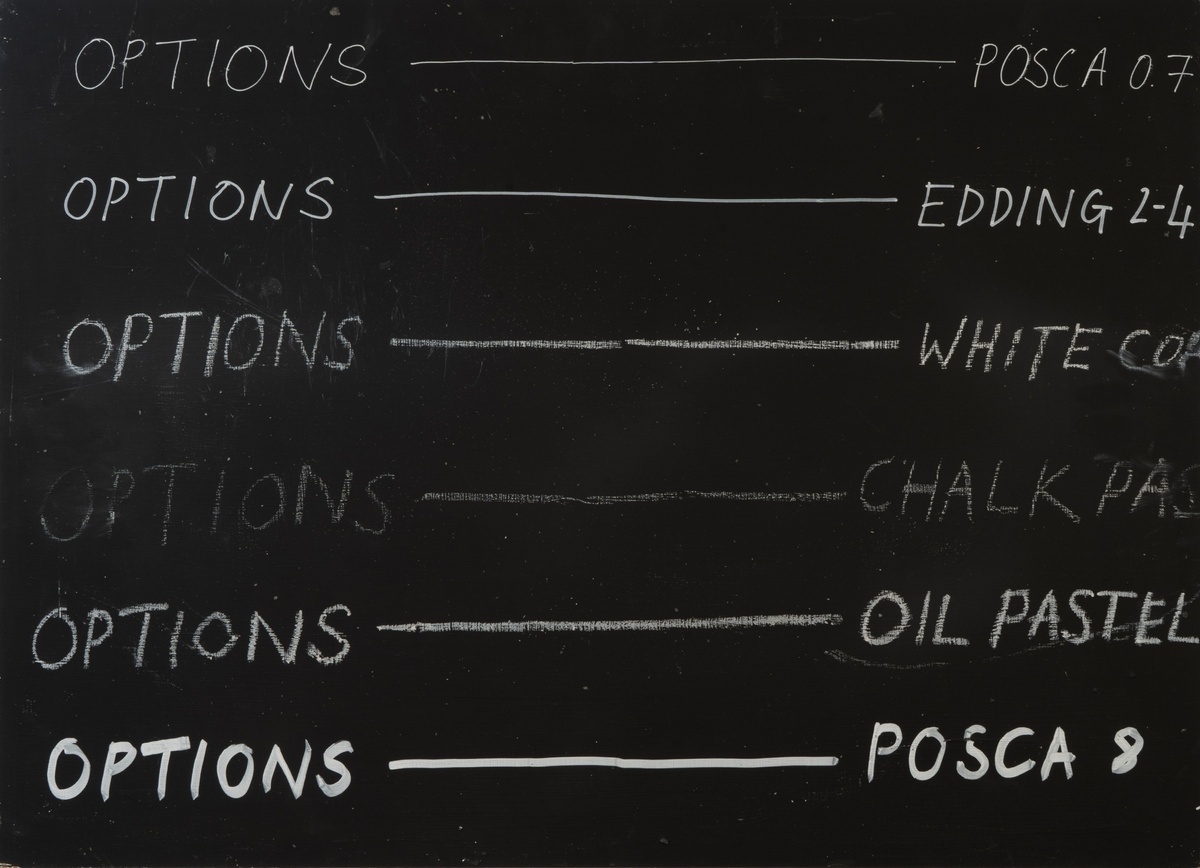

Kemang Wa Lehulere works against collective forgetting and gives to South Africa’s recent past images, objects and gestures – each a mnemonic sign for those stories lost in historical abstraction. Working between amnesia and archive, Wa Lehulere’s installations and performances become poetic translations of memory. Wa Lehulere counts among his many mediums collaboration, quotation, objects found and made, and chalk. To chalk he gives material significance, for its pedagogy, its fragility, the palimpsest of a blackboard. It extends, he suggests, “into broader ideas around history and memory; the writability of history… the erasure of history, the marginalisation of certain histories, and the re-writing of history.” Wa Lehulere’s historical impulse is not one of nostalgia, but rather a critical re-examination of inherited truths. History, after all, is not static but generative. To the artist, it lends itself to be reimagined and revised.

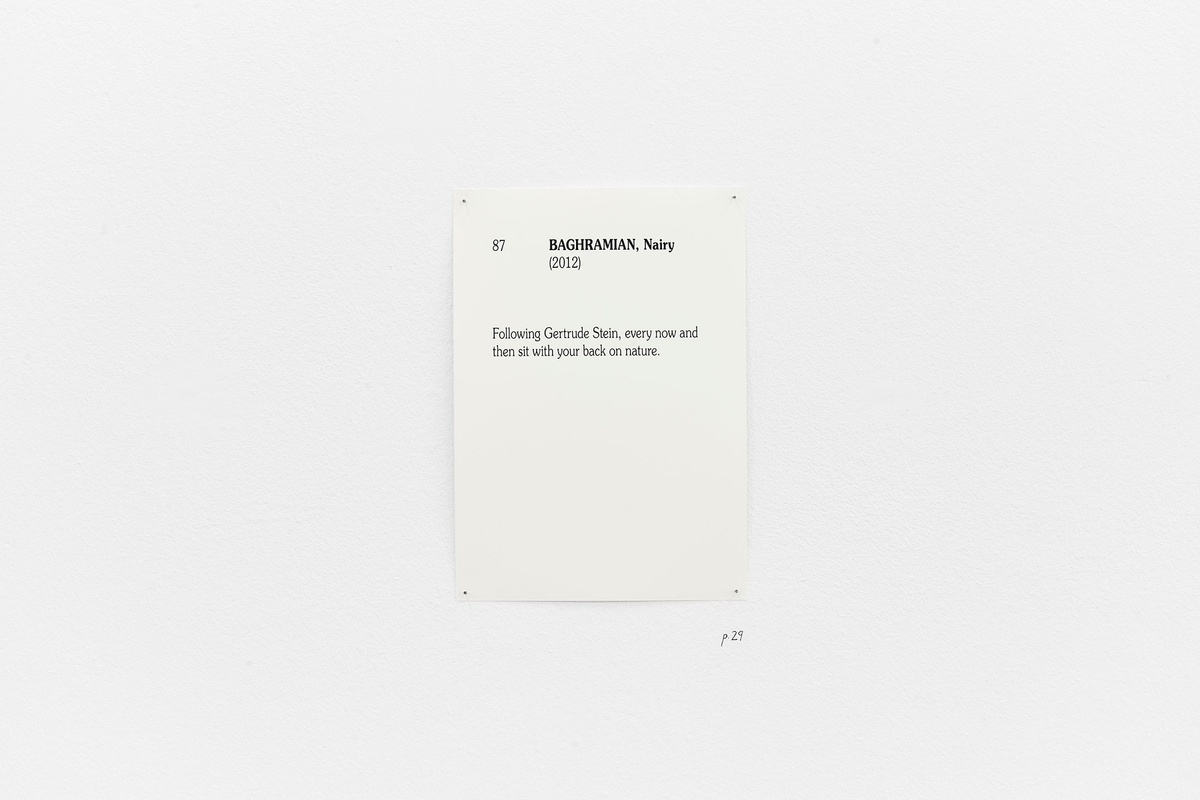

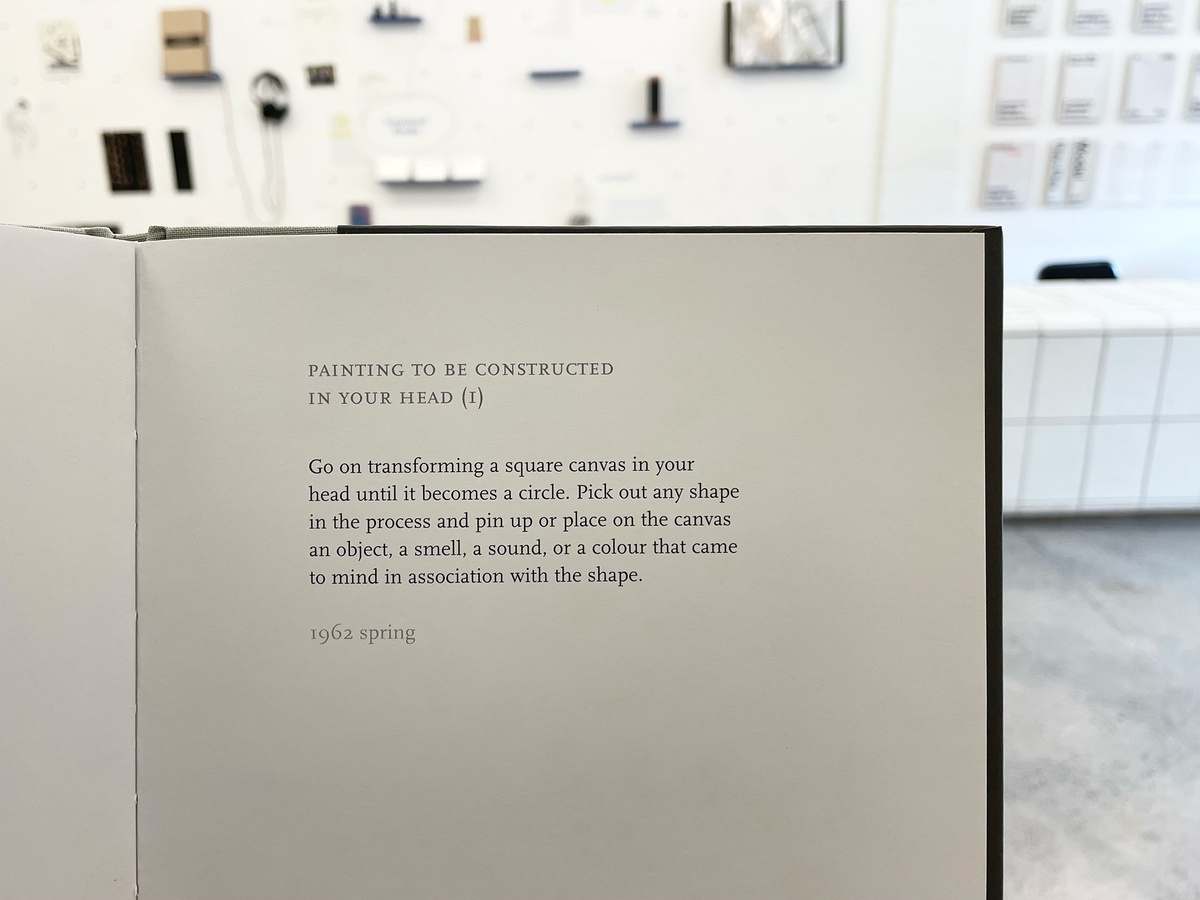

An introduction to instructional works. – February 3, 2025