Text:

Hedley Twidle

Editor:

Sara de Beer

Design:

Ben Johnson

The decade began, just a week ago, in eerie red light. First pitch darkness at nine in the morning because of the smoke, then a red light on the horizon as the fire front approached. This was in eastern Australia, where navy ships began evacuating those being driven into the sea by the bushfires, but it was also everywhere. We saw it on our screens and it joined that category of uncanny aesthetic phenomena being generated week to week as the planet moves deeper into the Anthropocene: weather maps inventing new shades of purple as heat records are shattered; shards of ancient black ice calving from Arctic shelves, tints that might never before have touched human eyes. White glaciers in New Zealand went a uniform dirty yellow from Australian ash, as if a finger on a touch screen had flicked past ‘sepia’ and ‘vintage’ to opt for the filter ‘post-apocalyptic’, now and forever. ‘Post-apocalyptic is the new normal’ read one headline; every day something really not normal at all is the new normal, so with luck this copy-writing concept – so deadening as it slickly tries to absorb the radically unknown so quickly and knowingly into the already known – will itself soon be normalized and abandoned. Instead I kept watching a clip of man wearing ski goggles, on his boat with wife and children under the red sky, the fire wind lifting up his hair like static as he reached the limits of language, Mallacoota style: ‘Fuck. We, ah, decided to, ah, fuck off from the fucking houses, and thank fuck we did, cos the fire front’s come through. Everyone’s safe and sound. Got the girls and the dog’s up front. Got supplies but, I hope everyone’s fuckin just fuckin fuck the houses man. Get into the water. It’s fuckin…chaos. Fuck. I’ve never seen anything like it. Hope everyone’s safe man. Good luck.’

We had been hoping for a little uptick in the news cycle, just a little shot of optimism, a little jauntiness to match the swing in the name of the decade, the twenties, and get it off to a good start. Just a little breather, even if it was plainly a news stunt, a pseudo-story or a global PR exercise. But in a gallery in Cape Town, a necklace of brake lights kept flashing in the dark – tick, tick, tick – amulets of risk and warning: Meshac Gaba’s Détresse. There’s a far greater risk of getting killed while driving to Koeberg nuclear plant than of dying in a meltdown, one is told; in the same way that driving to the beach is far riskier than dying of a shark bite. Both factoids, though, do little to make one feel less endangered near either ageing nuclear plants or Great White breeding grounds. Risk is something carefully calculated, quantified and calibrated; very carefully, since unimaginable amounts of money follow, and are premised on, risk and its rewards. Yet risk is also something obscurely felt, imperfectly guessed at, roughly estimated via the sensory equipment of an individual human body now toggling constantly between the actual and digital. Beyond the conflagrations both real and virtual, beyond the black mirror, beyond the op eds, the special reports, the live blogs, beyond the news as a profit-driven entertainment industry which must daily generate epic, unspooling dramas of risk, and uncertainty: what kind of danger are we in? How can we take risk at a planetary scale personally? Inhabit it feelingly? Must we? Should we? Can we? We?

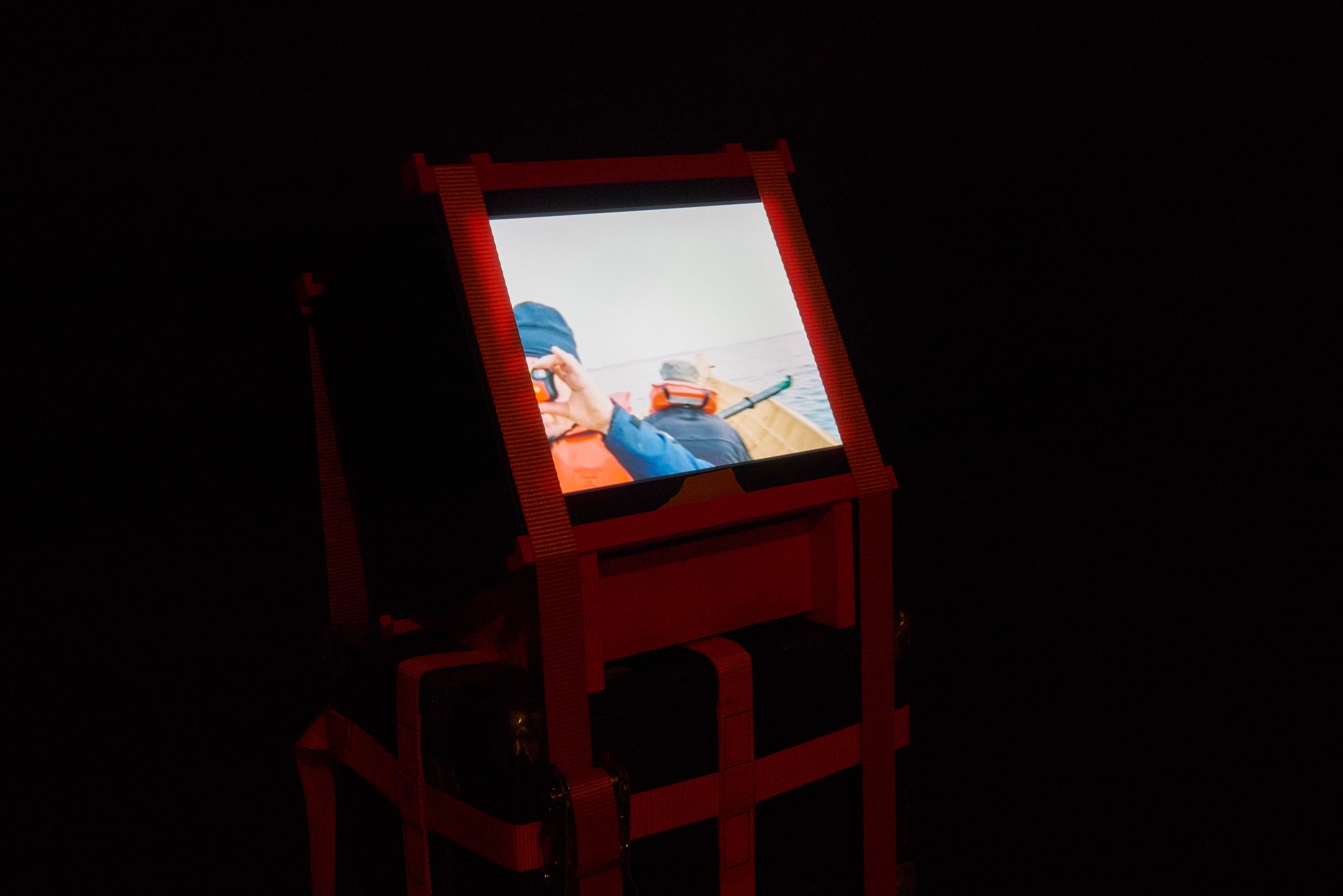

From my tiny screen full of fire to the larger screens of John Akomfrah’s Four Nocturnes: also filled with forest and brush fire, plus water, earth and wind in mesmeric high definition, dust storms, elephants mourning their dead, human figures walking through desiccated landscapes, Mount Kilimanjaro as the world’s navel, its snowcap soon to be a memory. The work unfolds as if made from the offcuts and out-takes of Planet Earth or National Geographic documentaries, the footage now no longer narrated and anchored by a soothing BBC voice, but allowed to propagate and run riot. Restless, random, noisy, portentous, the nature footage now writhing and recombining with scenes most common in most of the world – unfinished buildings; fallen pylons; a polluted beach; figures walking by the side of a dusty road as two trucks barrel past, SCANIA, MAN – yet seldom brought into the same frame as a time lapse of the rainforest floor.

Time lapse, it struck me while watching this, may be one of the oldest, most basic filmic effects. But it has never lost its fascination, the sense of something so direct and beautifully comprehensible – yet also obscurely meaningful, philosophical even – unfolding right before your eyes. Thunderstorms roil and scud across the sky; sea urchins and coral stitch together life underwater. Sunbeams break through clouds to strafe the ocean surface like searchlights. Fern fronds uncurl their long necks, sloughing off a casing that looks like brown plastic, but melts away in seconds. The human sensation of time, of being in time, it seems to say, is only one of a billion different temporalities, each of them having a logic and utter rightness of their own. When our being-in-time is momentarily blurred or deranged, an infinity of other timescales opens up, dizzyingly unshackled from the arbitrary parameters of human consciousness and from any fixed values. Who’s to say that ancient redwoods don’t experience existence as if it were an instant, while flying ants live through a day as if it were as long as the life of the sun itself?

‘From the earliest times’, writes W. G. Sebald, ‘human civilization has been no more than a strange luminescence growing more intense by the hour, of which no one can say when it will begin to wane and when it will fade away.’

In The Rings of Saturn, he witnesses a forest fire in Greece. The experience sets off a meditation on burning, one that has the sense (and this is the mysterious and mesmeric thing about this writer's prose) of large, unaccountable tracts of time having been distilled and preserved within it. It is a passage which shows how one of the great pleasures and powers of narrative discourse is that it can make time buckle and bend to its will, can stretch or speed up or slow down time as the paragraph moves from the fires of pre-historic Europe to the yellow sodium glow of lights along a Belgian motorway: ‘Combustion is the hidden principle behind every artefact we create. The making of a fish-hook, manufacture of a china cup, or production of a television programme, all depend on the same process of combustion. Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers.’

Responding to the New Year scenes in eastern Australia, the fire historian Stephen J. Pyne writes of two kinds of combustion that are becoming ever more entwined and threatening in the Anthropocene (or, as he prefers to call it, the Pyrocene): ‘One is overt – the fires that burn living landscapes, the bush. The other fire is covert, because it burns lithic landscapes. These are the once living, now fossilized biomasses such as coal and gas that we combust to power our industrial economies.’ We have, in other words, been burning and bingeing our way through unimaginable distillations and compressions of time: through the immensely concentrated sources of hydrocarbon – coal, oil, natural gas – produced by geological timescales and pressures. In California, the last years have seen the new socio-environmental phenomenon of pre-emptive ‘brownout’: power cuts to certain regions during times of high wind and extreme fire danger to prevent a blaze from sparking where the two infernos touch: ‘That so many fires in Australia (and California) start from power lines’, writes Pyne, ‘is an apt metaphor for the way the two realms of fire interact.’

Burning everything it touched and causing everything that touched it to burn: from the Pleistocene, through the Holocene to the Pyrocene, the entire human project, witnessed from space as a planetary time lapse, might be a noiseless flash, or a ripple of bioluminescence so quick as to be invisible.

The sixth extinction? ’Tis but a scratch, a microsecond in earth time. The end of everything that humankind has known, built, sung, loved or remembered – life will reboot and run riot again, other worms and corals and fronds stitching and unstitching, unfurling and furling. This is the odd, heretical paradox of running mental time lapse experiments, and of trying to inhabit non-human time. Opening ourselves up to it both reveals the severity of our predicament (human action has taken on the parameters of a geological agent, burning heedlessly through the credit balance of lithic landscapes) while also suggesting that in the long run (the very long run) perhaps none of it matters; perhaps it was always going to unfold this way: the proximity of fire-obsessed primates and such miraculous, addictive fuels. The result is the strange, dual demand of frenzied action and resigned fatalism (or is it rather a slow-motion grieving?) that seems a part of modern environmental consciousness: two ideas that are almost impossible to hold together in any rational argument, and yet can co-exist so intimately in the mind.

Alan Weisman’s 2017 book The World Without Us imagines what would happen to the natural and built environment if all humans disappeared overnight, as if in some kind of deep ecological vision of the Rapture. To watch the documentary based on this concept, one reviewer noted, is to feel the strange sensation of watching a disaster movie that is also a feel-good. Something of this ambiguity – what genre are we in? – resides in Akomfrah’s installation (even though it is in many ways a corrective to the depopulated vistas of Euro-American wilderness conservation and the Malthusian misanthropy of deep ecology). People and their suffering, or just their ordinariness, are never absented from its landscapes; yet it still leaves open the question of how to exactly calibrate the relation between dusty, bare human life and the elemental scenes of other presences that swathe it: flowing, germinating, propagating, stitching, evaporating.

As with the beautiful smell of ozone after a nuclear explosion, or the hydrocarbon particulates that create uncannily vivid sunsets, the poetics of the Anthropocene take us into an indeterminate zone where aesthetic beauty is an unreliable guide, where one doesn’t quite know what to feel, or feels supposedly incompatible things at the same time, things not easily absorbed into any new normal. An unspeakable sadness for the extinction and disorder we have kindled, mixed with a deep release into what comes beyond and after the human, an ethical lapse into the time of rocks, bacteria, corals and viruses. The post-Anthropocene explosion of life that will surely come, the ‘endless forms’ of organic evolution that need only the near infinite resource of time.

As the Nocturnes ended, I had the thought that, I think, many of us have, but which is dangerous to say out loud in right-thinking circles. It’s too late. It’s over. We’re locked in. Cycles that far exceed human agency and political will have been set in motion, and no amount of smacking down climate denialist uncles on social media is going to change that (the texture of life in the twenties, future generations take note: million-year old organisms are vanishing hourly, wet forests of the Australian escarpment are burning for the first time in recorded history, and mostly I am thinking of all the fuel that the fire is giving me against some libertarian, free market uncle who can’t seem to stop trolling the pieces that I share by Rebecca Solnit and Bill McKibben on the Green New Deal).

Even to acknowledge this, however, is another kind of risk, as Jonathan Franzen found out when he wondered ‘What if we stopped pretending the climate apocalypse can be stopped?’ for the New Yorker, swiftly earning the ire of Solnit and other climate activists online. ‘You can keep on hoping that catastrophe is preventable’, wrote Franzen, ‘And feel even more frustrated by the world’s inaction. Or you can accept that disaster is coming, and begin to rethink what it means to have hope’. He went on to claim that scientific predictions around climate change often err on the side of least risky, and so the numbers we pin hopes of meaningful political action on – 1,5 degrees, 2 degrees – are in some ways a form of magical thinking. A false hope of salvation may be actively harmful: ‘If you persist in believing that catastrophe can be averted, you commit yourself to tackling a problem so immense that it needs to be everyone’s priority forever.’ Rather start where you are, his argument boils down to, and with what you love.

A risky argument, in the current climate. But risk, Franzen suggests elsewhere, the risk of shame and embarrassment, is the property that distinguishes fearless writing: ‘The writer has to be like the firefighter, whose job, while everyone else is fleeing the flames, is to run straight into them. Your material feels too hot, too shameful to even think about? Therefore you must write about it.’ The risk of being misunderstood. Not just misunderstood, but entirely, catastrophically misunderstood. The risk of being wilfully misread. The risk of an argument being taken up for purposes that are entirely, diametrically opposite to everything that its creator has believed and worked for. The fact that saying something important and liberating may exist a hair’s breadth away from its opposite and antithesis, and the risk that most people will not discern the difference. The risk that none of that matters now anyway.

Everyone’s safe and sound

Got the girls and the dog’s up front

Got supplies but, I hope everyone’s fuckin

just fuckin fuck the houses man.

Get into the water. It’s fuckin…

Chaos.

Fuck.

I’ve never seen anything like it.

Hope everyone’s safe man.

Good luck.

Hedley Twidle is a writer, teacher and researcher based at the University of Cape Town. His essay collection, Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World, was published by Kwela Books in 2017. Experiments with Truth, a study of narrative non-fiction and the South African transition, appeared in the African Articulation series from James Currey in 2019.

This essay appears in Risk in Writing to be published by A4 Press, a collection of responses to the exhibition Risk at A4 Arts Foundation. The anthology assembles poetry, prose, and musical composition and includes contributions by Kathryn Smith, Bongani Kona, Derek Gripper, Siphokazi Jonas, Toni Stuart, Bill Nasson, and is edited by Sara de Beer, with book design by Ben Johnson. Risk in Writing asks after artworks as prompts towards further artistic research and creative production.