William Kentridge

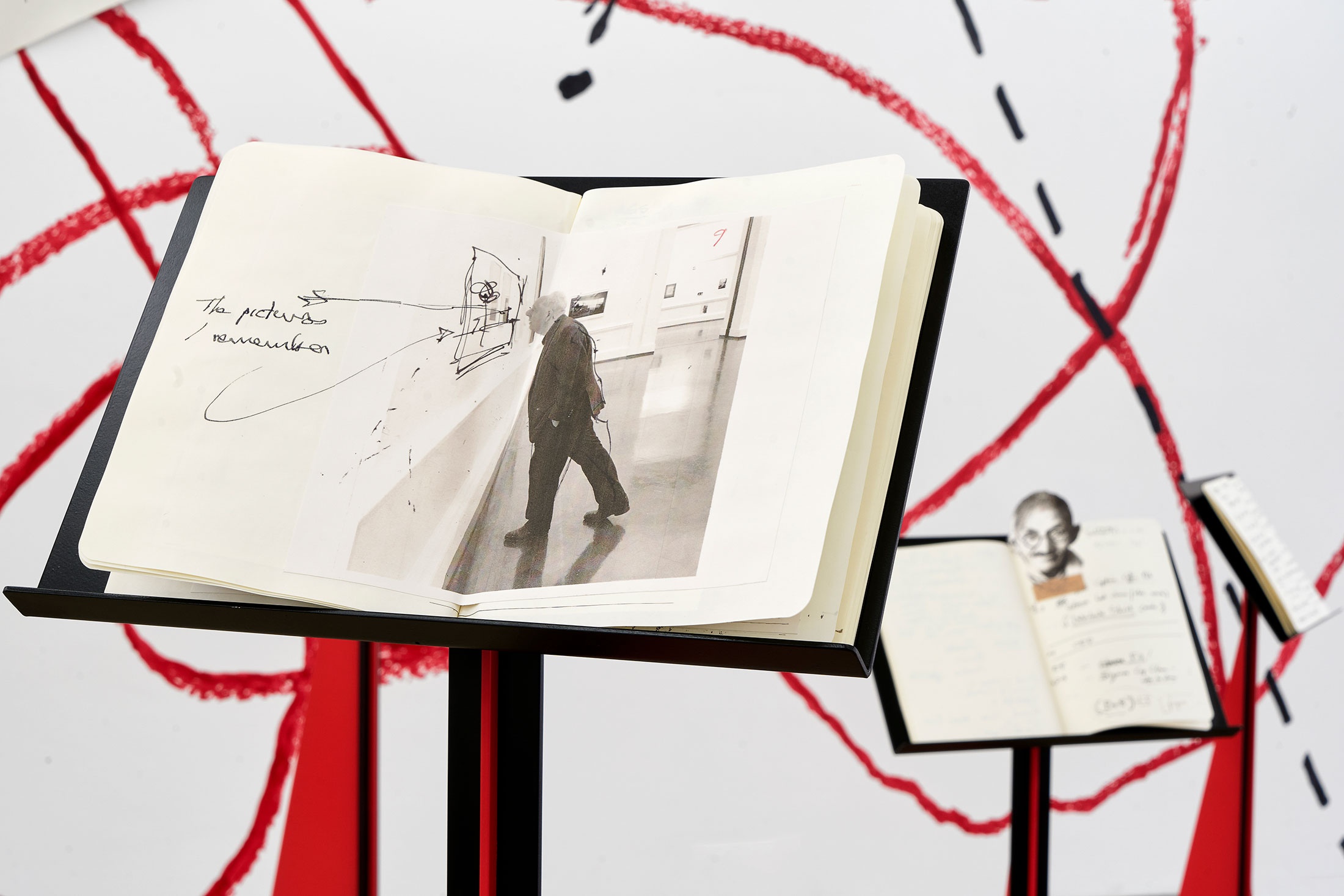

The 30 notebooks created for History on One Leg (selected from more than 120 made over the last 15 years) are significant tools for working in William Kentridge’s studio. Composed for different kinds of tasks, they help the studio perform its various functions. Among these are notebooks for projects with their diagrams, scores, librettos, lectures, sketches, plans; notebooks of drawings for film; notebooks of studio ‘to-do’ lists; notebooks for meandering in the margins; notebooks of walks; notebooks of Words.

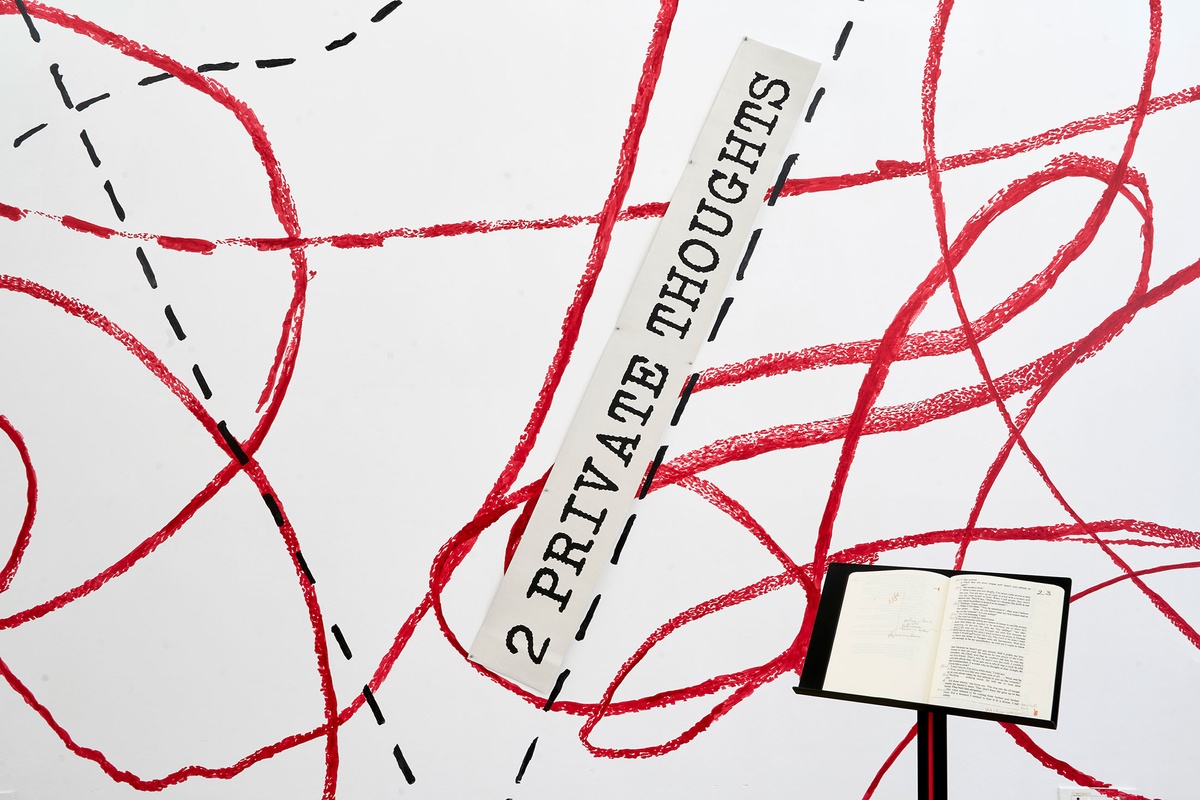

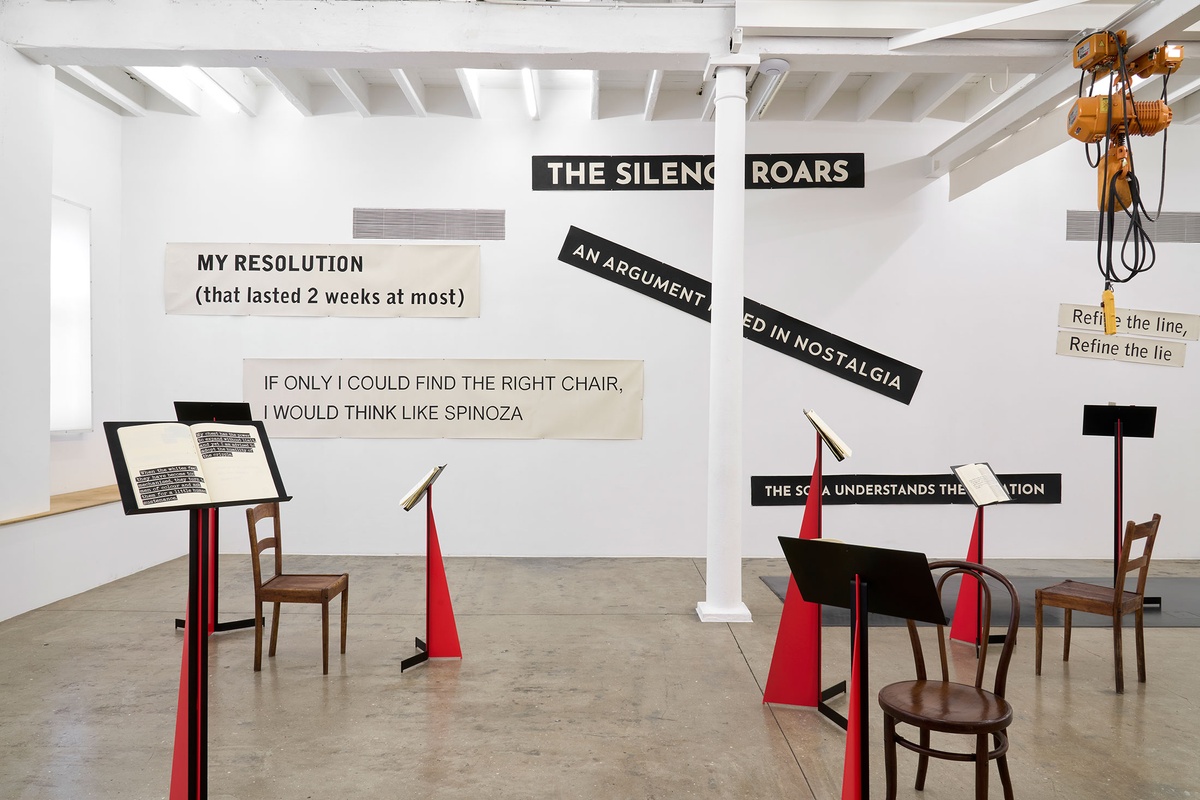

Josh Ginsburg’s engagement with Kentridge’s notebooks began in 2012. He spent 10 days in the artist’s studio where he came upon Kentridge’s Norton performance lectures scripted in notebooks, finding a “raw home for this kind of work.” Twelve years on from this first encounter, the notebook is now the focus for engagement at A4. Presented on custom-built structures that resemble the music stands for an orchestra, time spent browsing their pages – deciphering the handwriting and diagrammatic sketches – reveals a portal into a particular mode of thought that is, according to the artist: “thinking forwards, not retrospectively. Notebooks are for thinking, how can this be done?” These are working documents. Within the rudimentary and rough lines (there to remind the artist of a drawing he wants to make, of an exhibition’s scenography, or the set pieces for a stage), there are parts to these books that reveal marks on the heart.

In Words (March 2014, 2016, 2018), it is written:

What we see and what we know.

Tell them about

Tell them about

I wanted to make my

Mother(land) happy.

The 9 year old in the

55 year old

Turning the page:

Struggle for a good Heart. –

Strengthen the branch

Expedite the budding

Make the Mother(land) proud.

A few pages on, a line from Second Hand Time (2013) by Svetlana Alexievich in English translation written out by the artist in November 2016 reads: Kind words make me cry harder than gunshots.

Then there are the small thoughts, quite unserious, that document meandering and sideways routes that thinking takes.

I am trying to keep track of life in the studio. There are other ideas hovering at the wings…

I am meant to be talking about the importance of the margins – but I can’t stop thinking about mangoes.

As for the title of the exhibition? The phrase History on One Leg appears in the notebook If the good doctor…/a defence of the less good idea (March 2017) / BRUGES, mentioning the story of Hillel, a Jewish sage who summarises his beliefs in one sentence to an impatient man, only able to listen for the length of time he can balance on one leg. Kentridge goes on to name the South African Toyi-Toyi, a marching, jumping dance shifting from one leg to another performed as a rally to protest, as a reference.

In Studio Life, Episode Translations Nov 2020, you’ll find where Kentridge writes, “What does a poem say? If you understand it, very little.” A few pages back, a riff on that line: “What does a picture say. Very little if you understand it.” Together, the notebooks offer insight into what is saved and savoured – the sustenance of creative work – and a read into Kentridge’s practice outside of parenthesis.

b.1955, Johannesburg

Performing the character of the artist working on the stage (in the world) of the studio, William Kentridge centres art-making as primary action, preoccupation, and plot. Appearing across mediums as his own best actor, he draws an autobiography in walks across pages of notebooks, megaphones shouting poetry as propaganda, making a song and dance in his studio as chief conjuror in a creative play. Looking at his work, a ceaseless output and extraordinary contribution to the South African cultural landscape, one finds a repetition of people, places and histories: the city of Johannesburg, a white stinkwood tree in the garden of his childhood home (one of two planted when he was nine years old), his father (Sir Sydney Kentridge) and mother (Felicia Kentridge), both of whom contributed greatly to the dissolution of apartheid as lawyers and activists. The Kentridge home, where the artist still lives today, was populated in his childhood by his parents’ artist friends and political collaborators, a milieu that proved formative in his ongoing engagement with world histories of expansionism and oppression throughout the 20th century. Parallel to – or rather, entangled with – these reflections is an enquiry into art historical movements, particularly those that press language to unexpected ends, such as Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism.

Moving dextrously from the particular and personal to the global political terrain, Kentridge returns to metabolise these findings in the working home of the artist’s studio, where the practitioner is staged as a public figure making visible his modes of investigation. Celebrated as a leading artist of the 21st century, Kentridge is the artistic director of operas and orchestras, from Sydney to London to Paris to New York to Cape Town, known for his collaborative way of working that prioritises thinking together with fellow practitioners skilled in their disciplines (for example, as composers, as dancers). Most often, he is someone who draws, in charcoal, in pencil and pencil crayon, in ink, the gestures and mark-making assured. In a collection of books for which A4 acted as custodian during the exhibition History on One Leg, one finds 200 publications devoted to Kentridge’s practice. In the end, he has said, the work that emerges is who you are.