Mitchell Gilbert Messina

Play for Artworks, directed by Mitchell Gilbert Messina, began during Parallel Play v.2, when artists Asemahle Ntlonti and Kyle Morland were invited to make mobile studios in A4’s Gallery in between the exhibitions Customs and The Future Is Behind Us.

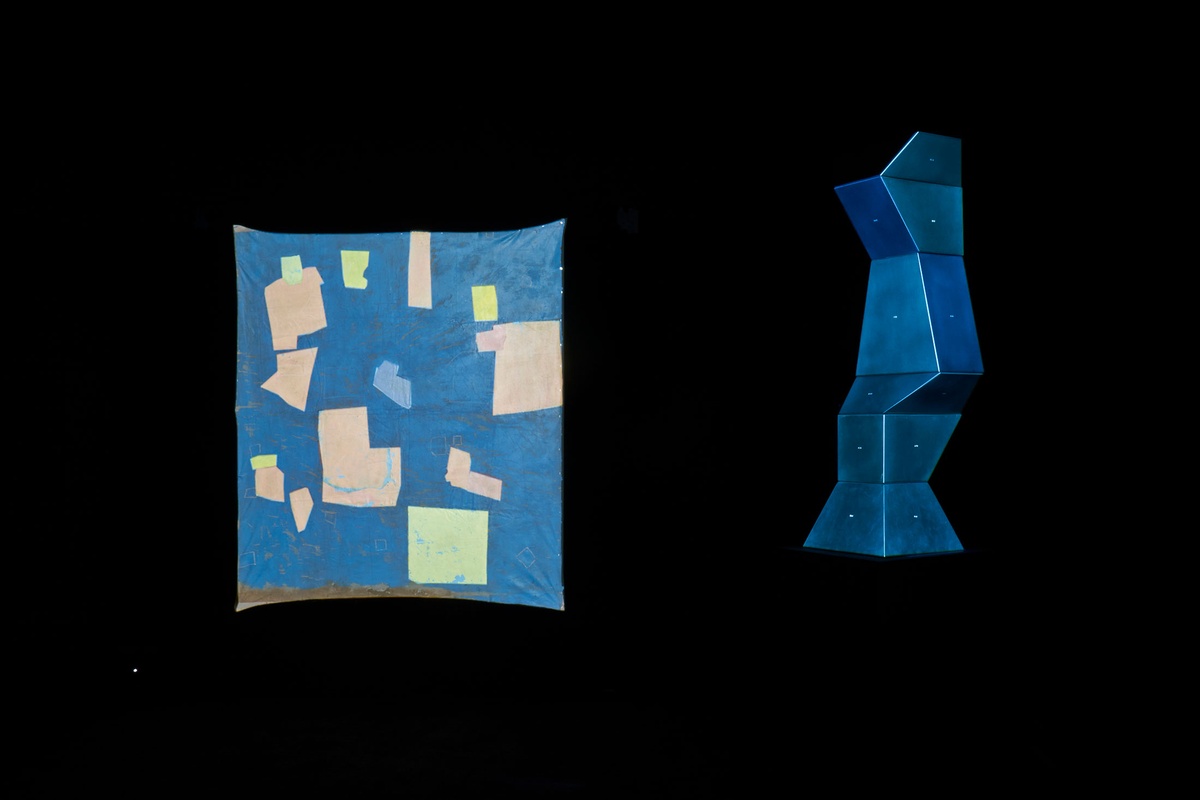

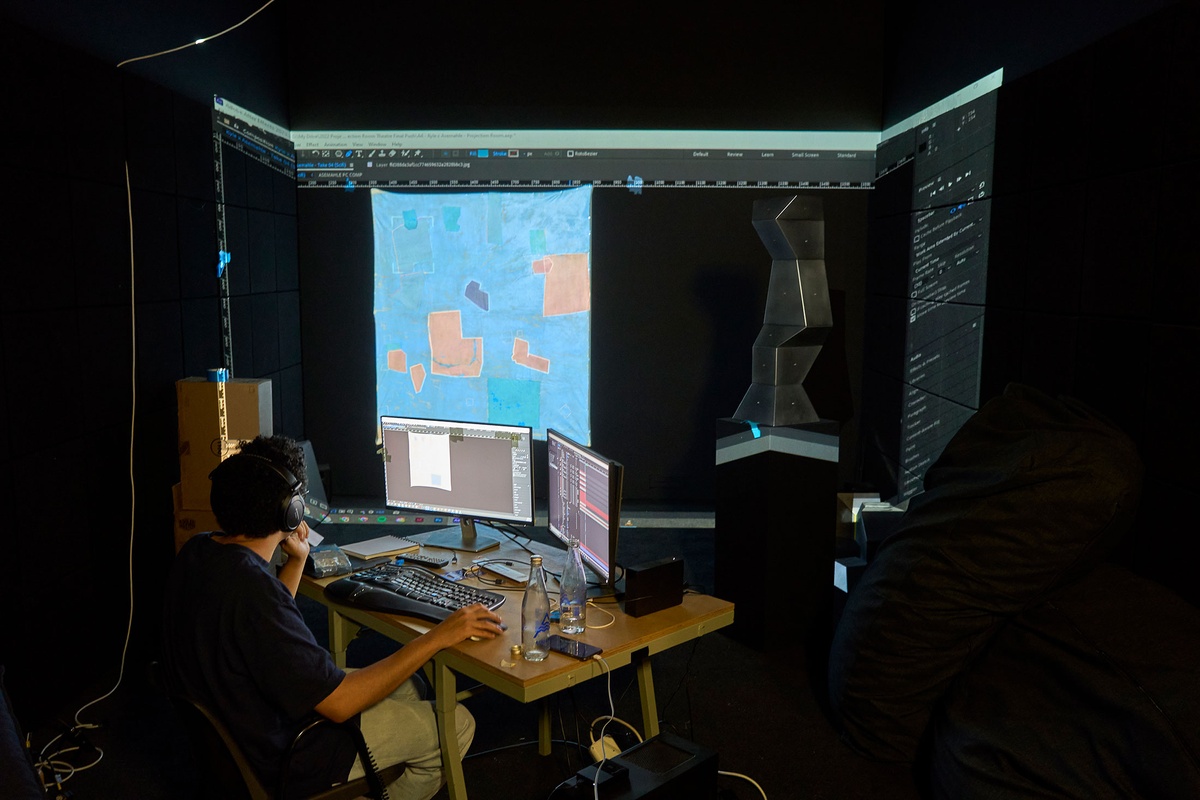

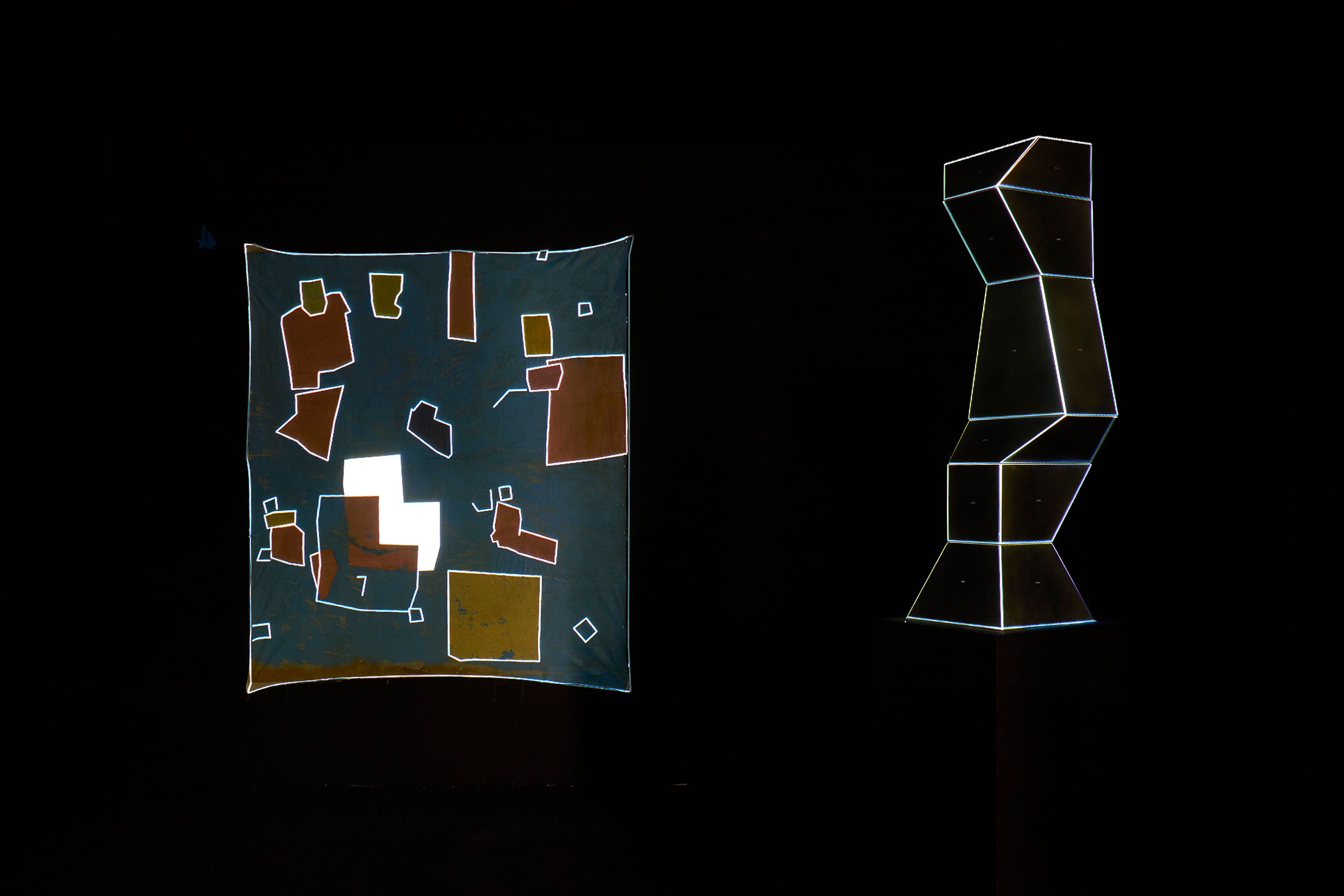

Asemahle Ntlonti’s Intaba is stapled to the wall. A sculpture that Kyle Morland put together incidentally – accidentally – stands on a plinth. Mitchell Gilbert Messina animates their surfaces with light and lends their conversation sound.

–

What follows is an excerpt from a conversation between Asemahle Ntlonti (A.N.), Kyle Morland (K.N.), Jean-Marié Malan (J.M.N.), Anelisa Ntlonti (A.N.N.), Sean O’Toole (S.O.T.), Sara de Beer (S.D.B.), Mitchell Gilbert Messina (M.G.M.), Nkhensani Mkhari (N.M.) and Josh Ginsburg (J.G.) on the occasion of Parallel Play v.2, 25 November, 2022.

J.G. When we started this instance of Parallel Play, it wasn’t done on the basis that there would be overlaps in the coordinates of Kyle and Asemahle’s practices but many interesting and unexpected touch points have arisen.

M.G.M. Both Asemahle and Kyle’s practices involve making and moving things until they settle. When does the work rest? When do you stop shifting? When do you feel a work is finished?

A.N. I begin with an idea, but as I make, new things arrive. The idea changes; I follow new directions. Before I start on the big work, I’ll sometimes work on small ones to offload what is in my head. If I can’t answer or resolve the work at the time, I turn over the next page, in a way. This is a process like writing: when I write in my notebook, I don’t use a full page. There will be two sentences, on different pages.

K.M. Once you’ve preserved a form, it’s finished. Once the form has been sanded and sealed. I follow a series of steps towards resolution. It’s a given logic.

S.O.T. Thinking of two verbs: work and play. Work is directional but play can accommodate failure. There is experiment in the first but also a formality. Perhaps you accept failure in play; you are released from the idea of a final work.

A.N. For me, the distinction between work and play can be challenging at times. Are you playing for the sake of playing, or because you want something out of it? Are you being honest in your playing? It’s probably a bit of both. But play is always productive; you can salvage things created in play.

A.N. I revisit my pile of discarded things. Visitors to the studio are drawn to it. These things have potential: a pile of things I don’t have a place for, yet.

J.G. A target is a thing that one is driven to realise in all its precision. Then is the detritus; the tests that generate these beautiful objects along the way.

M.G.M. How does the looking look? What is the research behind the practice?

K.M. Trying and trying again. Trial and error. Learning. There isn’t frustration, just work and problem-solving. I don’t engage in intentional research nowadays; rather, I pursue conversations with studio peers and other practitioners. I understand my work within a lineage but I no longer feel preoccupied with it.

A.N. I research to understand myself, having conversations with people because my history is not vastly written about. What is abstraction for me as a Xhosa person from the Eastern Cape? This is not resolved. I have to challenge myself – this is my research.

J.G. In your work, Asemahle, there are senses of both excavation and topological compositions. Both are part of the same discipline, the ground seen from different proximities like two geometries on a shared plane.

Non-objective art is an imagining of pure form, an art without pictorial subject. But in your case, your works refer explicitly to something while maintaining their formal abstraction.

S.D.B. There is also – in both Kyle and Asemahle’s practices – a shared engagement with the multiple, with assemblage and collage. There are so many different things happening, and opportunities for things to happen in ways other than what they were initially intended.

M.G.M. [After a pause] What sound would your artwork make?

b.1991, Nababeep

Offering humorous insights into the serious business of art-making, Mitchell Gilbert Messina’s “joke gestures” extend curiously compelling reflections on his chosen subjects; be it the state of video art after Youtube introduced its autoplay feature, an imagined siege of the British Museum, an animated exposé on an African art institution, or a fictional ‘curator emulator’ for online exhibitions. A “post-internet collagist” – to borrow from Sean O’Toole – Messina pairs a light-hearted playfulness and sense of provisionality with pointed institutional critique.