Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo

To develop a selection of photographs for the exhibition You to Me, Me to You, Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo was invited to take up residence at A4 Arts Foundation.

–

An excerpt from a conversation with Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo (T.H.) and Josh Ginsburg (J.G.), held in person in preparation for You to Me, Me to You, 4 August 2023:

J.G. There is a lineage of photographers and photo-documentarians but your material negotiation is more akin to the way Moshekwa Langa works. He has a material dexterity. How did you get into photography?

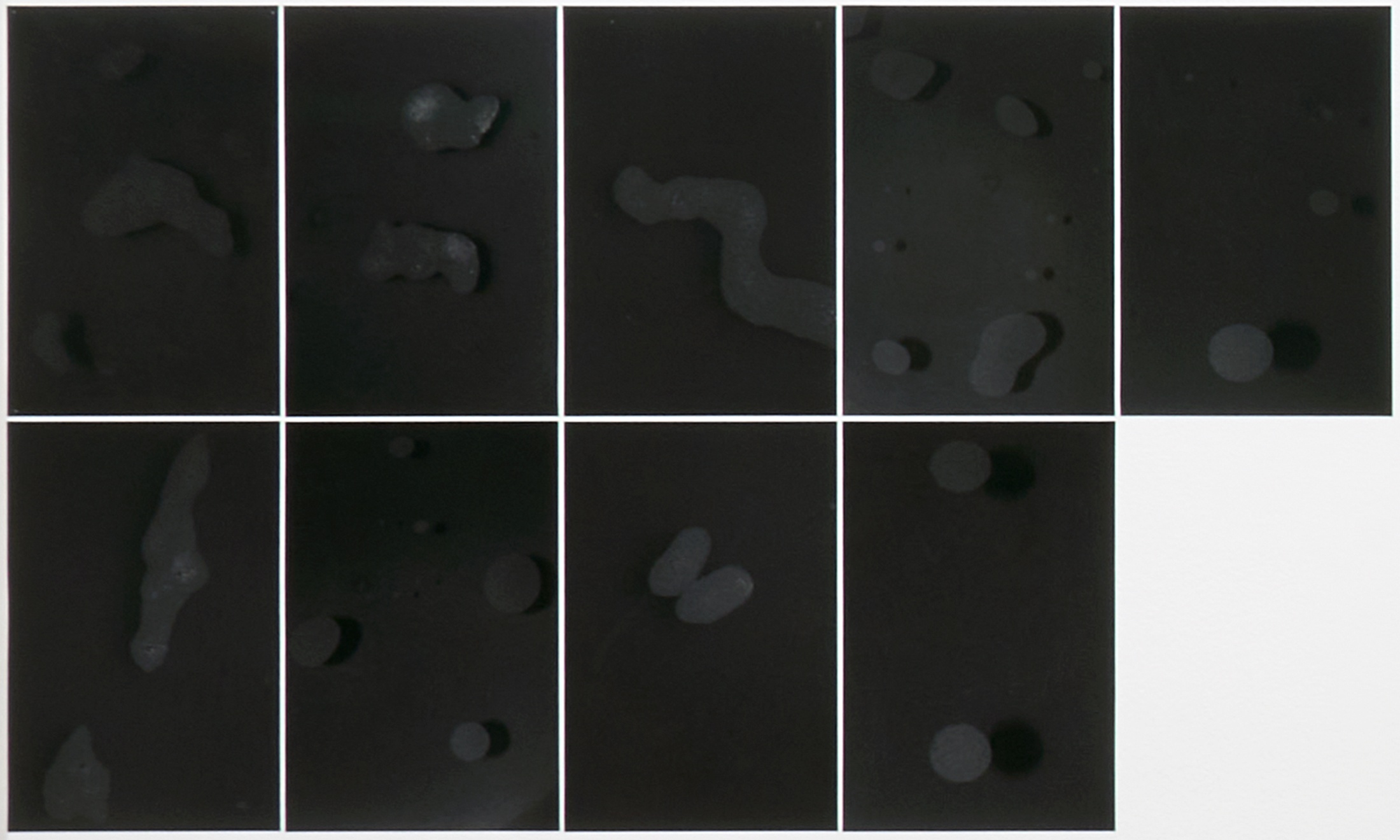

T.H. I joined Of Soul and Joy in 2016 and the journey of me being exposed to bodies of work and storytelling began. In 2018, I went to the Market Photo Workshop. At the time, I had begun trying to confront my childhood memories of the tavern and how it affected me. This is a tavern my family runs still, in the deep south of Johannesburg. The tavern always had interesting marks. From the marks, you could tell what was happening the previous night. Because of the violence, the community called the tavern Slaghuis (slaughterhouse). My process was informed by the word “slaghuis,” the violence in it. So I became violent with the image. I would also take images and put them back into the tavern, for the images to act as (recording) surfaces in the space.

J.G. It makes the work entirely robust. It only grows through contact with the world. It can’t be damaged, it can only collect. But if a love isn’t returned, what is it? Is it necessarily reciprocal? Does it rely on consent or can it be given without return?

T.H. My role is to accept the impermanence of things. That, for me, is an act of love. So it can be given without return because it’s already there.

J.G. You can’t lose anything that’s always there, so you need not possess it. How has your perception changed?

T.H. There’s something empowering about going back to a space that caused you harm and that you wanted to escape from. Having a conversation with that space and taking your power back from it.

b.1993, Johannesburg

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo’s first encounter with his parents’ tavern, an extension to his family’s home in the Lawley township outside of Johannesburg, was through a window – his view obscured by burglar bars and a lace curtain. “Nothing was clear,” says Hlatshwayo. “That influenced how I started working with the layering of the photos. The not-so-easily-accessible image.” Resisting ideals of scenography, Hlatshwayo photographs aftermaths – the marks leftover after actions. This is not a forensic investigation on the part of the artist, where these marks could be sought for evidence, the path rewound in the hopes of reconstructing past events. Instead, Hlatshwayo asserts the marks’ primacy – as fascinating in and of themselves – by placing the photographs he has printed in compromising situations. On a table in a bar, drink and ash fall on the surface. Intervention is inevitable, he seems to be saying through this action: we may as well invite it, as willing participants in time’s march. “Things are always moving, things never die, they move, and my role in this movement is to accept it all, the impermanence of things, that for me is an act of love.”