Dexter Dalwood

In Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, Jorge Luis Borges has an unnamed author come to the defence of Menard.

Those who have insinuated that Menard devoted his life to writing a contemporary Quixote besmirch his illustrious memory, begins an unnamed writer, He did not want to compose another Quixote, which surely is easy enough – he wanted to compose the Quixote. Nor, surely, need one be obliged to note that his goal was never a mechanical transcription of the original; he had no intention of copying it. His admirable ambition was to produce a number of pages which coincided – word for word and line for line – with those of Miguel de Cervantes... Being, somehow, Cervantes, and arriving thereby at the Quixote – that looked to Menard less challenging (and therefore less interesting) than continuing to be Pierre Menard and coming to the Quixote through the experiences of Pierre Menard.

And from Menard, himself?

The task I have undertaken is not in essence difficult… I have assumed the mysterious obligation to reconstruct, word for word, the novel that for him was spontaneous... Not for nothing have three hundred years elapsed, freighted with the most complex events. Among those events, to mention but one, is the Quixote itself.*

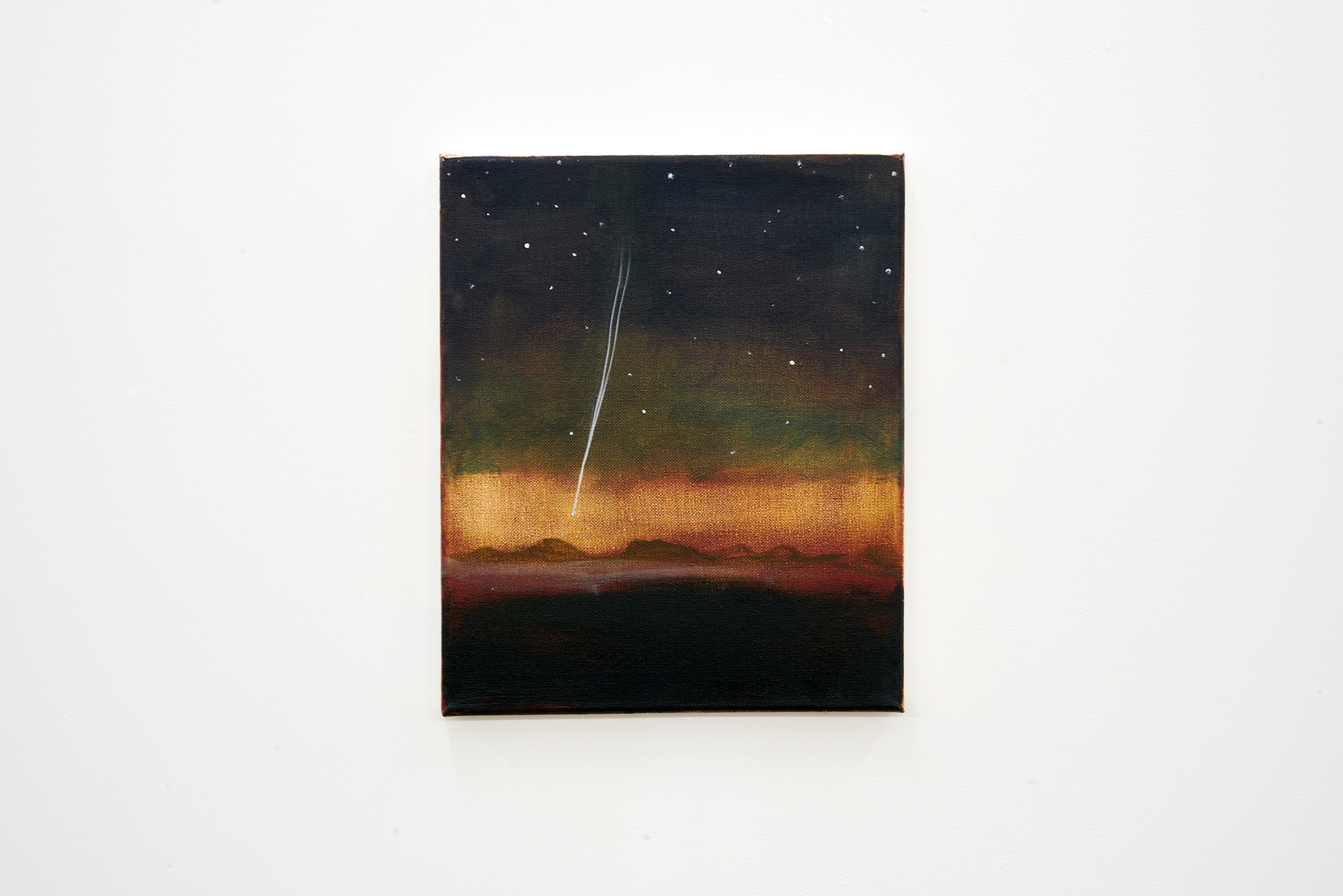

For You To Me, Me to You, Dalwood lent to the curator a painting that Dalwood had made after the painting The Great Comet of 1843 by the British astronomer (and amateur painter), Charles Piazzi Smyth. Dalwood discovered, after agreeing to send this work to A4 for the exhibition, that Piazzi Smyth had been stationed at the Royal Observatory in the then Cape of Good Hope when he painted this work, considered to be an eyewitness account of the comet’s trajectory. ‘Obs’, as the suburb is fondly known, is not a ten-minute drive from A4’s location in District Six.

*Jorge Luis Borges, Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote (1939).

b.1960, Bristol

Dexter Dalwood tackles painting with the integrity of an anthropologist. “Having been at it so long, I can look at a painting and say ‘I have an idea of how to make that. I have an idea of how to construct it.’” More recently the artist’s methodology has been to paint paintings by painters, collecting data points en route to a work’s making. This occupation requires, one imagines, the discipline of a method actor. His is a physical engagement with the canon, digesting art’s history by experiencing its moves and moments through his body, whether “going at the canvas like a bull” (De Kooning), or with the “patience of a watchmaker” (Magritte). Where Dalwood has long been a remixer of history in his paintings – finding fragments from elsewhere and reconfiguring them in the context of a work – he is, at present, less interested in mixing things up in one image, and more focused on individual paintings. To be clear: these paintings are not copies. What the artist refers to as “the picturing mind,” remains quintessentially Dexter Dalwood – that is, what an artist wants the painting to be, what he would like the viewer to think and negotiate when looking at an artwork. “The language of a painting is what you’ve decided is interesting for the painting in the particular moment you find yourself in,” he says. Where style is a “choice” – for instance, to mimic, modulate, or even antagonise – rather than anything inherent, the “picturing mind” remains more or less a constant companion through an artist’s oeuvre.