Colin Richards

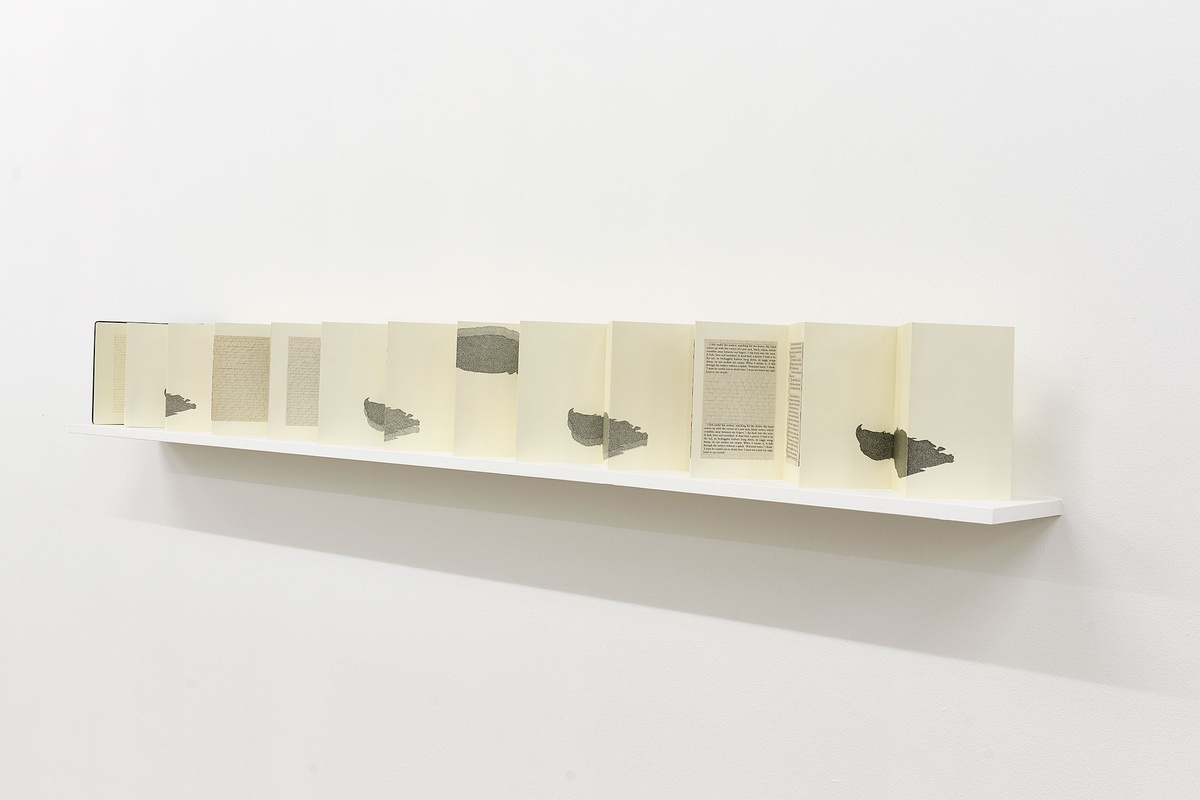

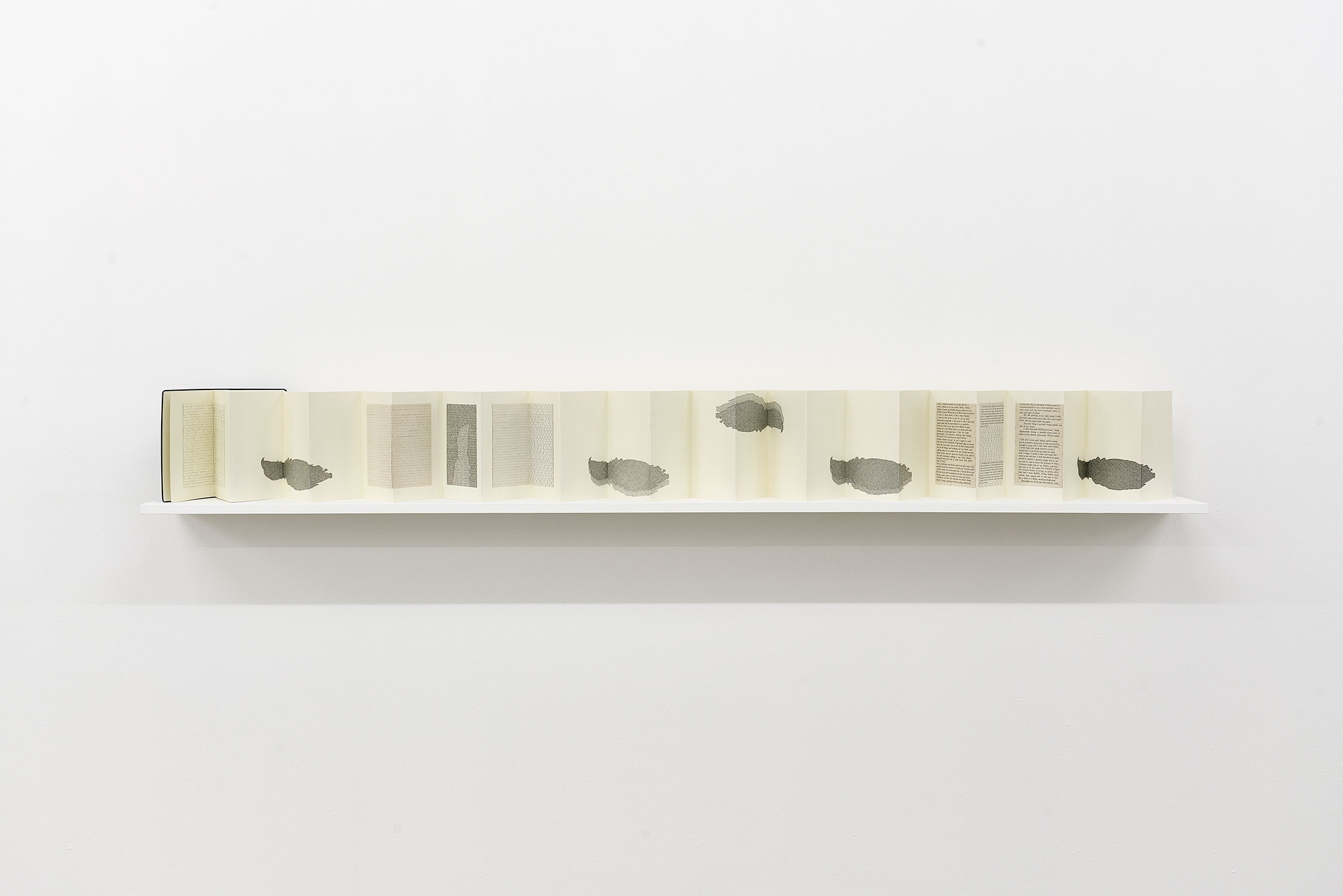

For Colin Richards, illustration offered a method through which to ask questions – to prompt investigative engagement – rather than an artistic medium. Describing Foirades/Fizzles (1976), the collaboration between Samuel Beckett and Jasper Johns to which he committed his PhD, Richards wrote, “Relationality lies at the heart of illustrational activity: relation between representation and objecthood, literariness and literalness, discourse and figure, similarity and difference.” In A Little After This, Richards facilitates relationships between paper and ink, between drawing and collage, and between intersecting lines. Richards’ interest in the concept of the line – which he thought to be like a hinge, consisting of the line itself, the inside of the line, and the outside of the line – is evinced in his detailed cross-hatching in pen, forming shadows from which silhouettes of parrots emerge. The parrots, drawn from colleague Pippa Skotnes’ taxidermied African Grey that she gave Richards, are seen lying on their backs – ambiguously suspended, and immortalised, in a place between life and death. The other pages consist of what Richards refers to as “horizontal hatchings,” paper reliefs and assembled words that reference parrots in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719). Writing on this work, Richards said:

Crusoe taught his parrot to speak and its words (his originally) brought him some comfort in his isolation. Yet other references in the book speak of killing parrots. I reorganized these cut and pasted words to touch on, amongst other things, the capriciousness of creaturely life – human and animal – lived in relative isolation.

By referring to those stranded on desert islands, A Little After This offers a parallel to the castaway’s diary, where time’s passing is marked in etched tallies.

b.1954, Cape Town; d.2012, Cape Town

Colin Richards’ artistic practice, conceptual in mode, is a call and response between theory and art-making, and vice versa. His training in meticulous labour and patience, as a medical illustrator at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Medical School, proved formative. Preoccupied with skilled mimicry – a matter familiar to the medical illustrator who must prioritise execution over interpretation – his research found a particular affinity for parrots while reflecting on originals, copies, and the ideal of a ‘true’ image. “Illustration is a hinge between the linguistic and the visual, and it can turn many ways,” he told Kathryn Smith. A devoted scholar of Samuel Beckett, Richards wrote, “To grapple with the unruly dynamics of power – the power of seduction, exclusion, coercion, complicity, liberation, oppression – requires a willingness to abstract and generalise in the moment.” His formidable intellect is remembered in obituaries written after his untimely death in 2012, his “catholic reading habits” (Sean O’Toole) that “amplified his gifts as a teacher and writer,” and his generosity as an educator, where, “he taught them not only how to think or write...” (Robyn Sassen) but “how to dare to say what mattered.”