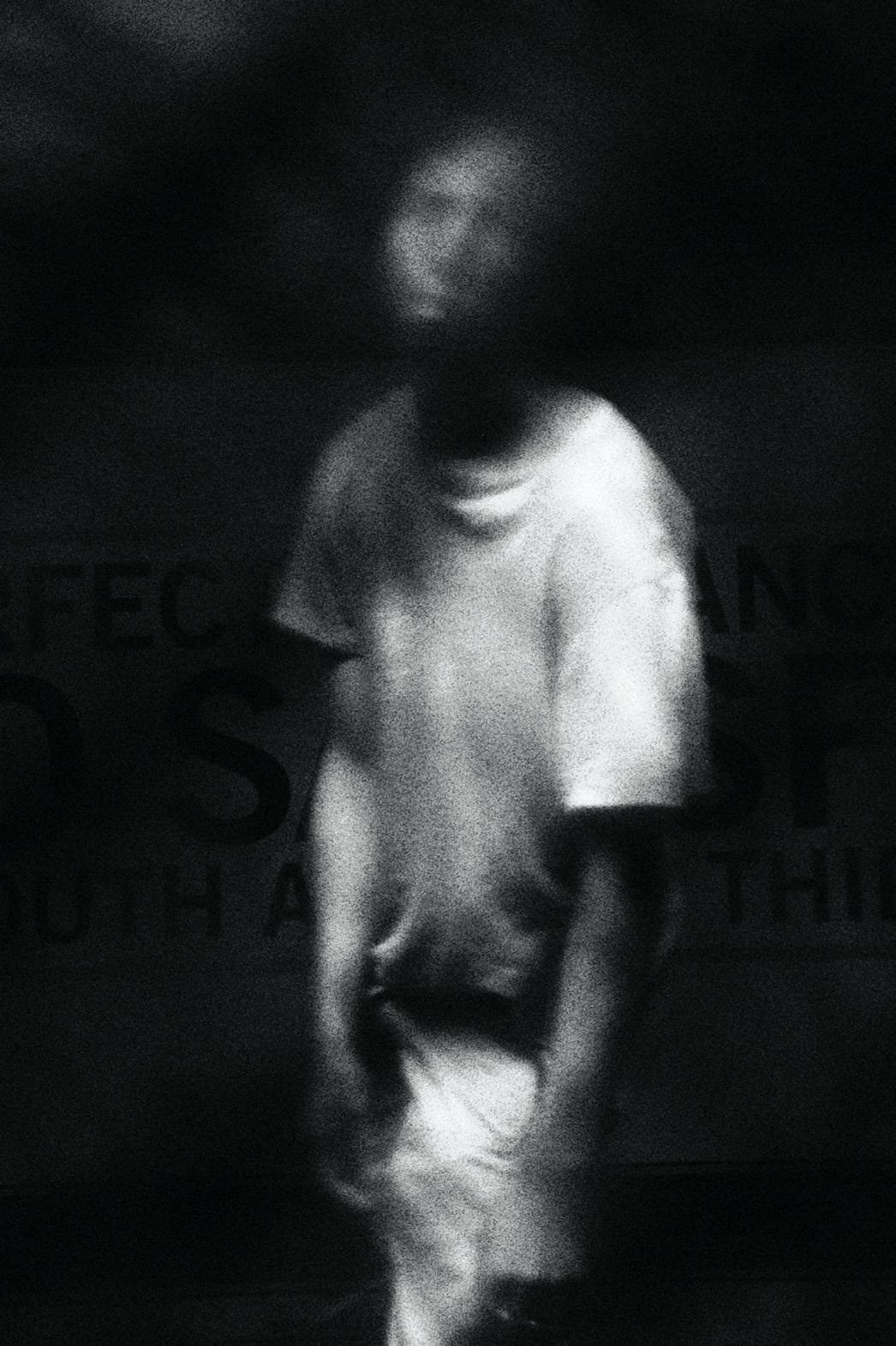

Haroon Gunn-Salie, James Matthews

Haunting in the absence it evokes, Gunn-Salie’s Amongst Men commemorates Imam Abdullah Haron, a South African religious leader and activist killed in police custody in 1969. The sixty kufiyas, each cast in white medium and suspended from the ceiling, together stand as metonym for the Imam’s funeral, which was attended by some 40 000 mourners. Accompanying this gathering of unseen bodies, a disembodied voice recites a poem written at the time of his death. “In a prison they placed him / His guilt, his plea for justice,” the poet James Matthews intones, reading aloud his Patriot or Terrorist as an elegy to the Imam’s memory. In its invocations, the work extends beyond the Imam’s burial to consider the role of Islam in the struggle against apartheid, and that of religion and resistance more broadly.

Amongst Men was made in conversation with Imam Haron’s widow and daughter, Galiema Haron and Fatiema Haron-Masoet.

b.1989, Cape Town

“I was always raised to be an activist,” Haroon Gunn-Salie says, “born a recruit. I was raised in a military cell… That has always left me with an innate desire to want to do something, to want to keep going with a struggle that I don’t yet believe has been realised.” The child of an anti-apartheid activist and member of the ANC’s armed wing, Gunn-Salie’s work is shaped by an urgent sense of social justice and civic responsibility. With collaborative interventions and installations, he considers the country’s imperfect transition from under the long shadow of apartheid. His process is one of dialogue and exchange, collecting the oral histories that inform his artistic offerings. “How do you articulate trauma?” The artist asks. It is a question that pervades Gunn-Salie’s practice; that he might better reflect memory and mourning, might meaningfully evoke past moments of shared significance. In distilling historic events into eloquent expressions – the forced removals of District Six in the late 1960s, the Purple Rain protest in 1989, the Marikana Massacre in 2012 – he gives to communal feeling a material expression.