Ane Hjort Guttu

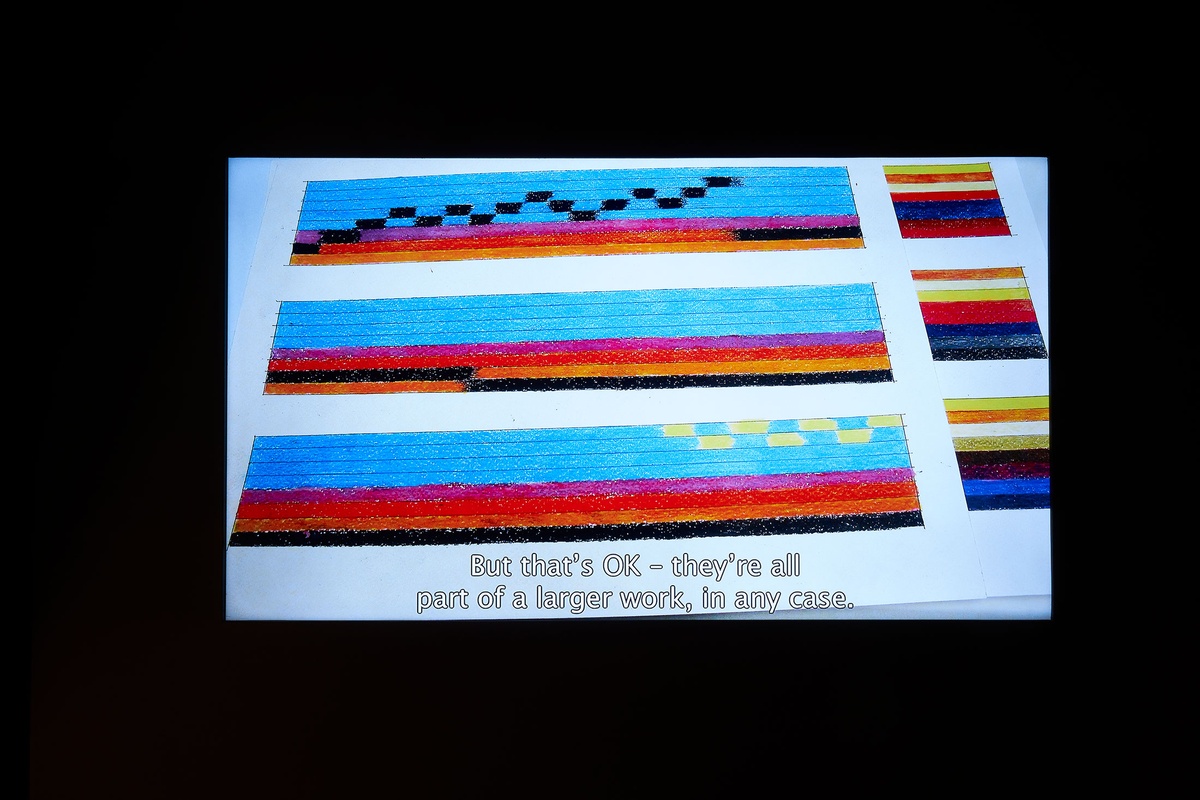

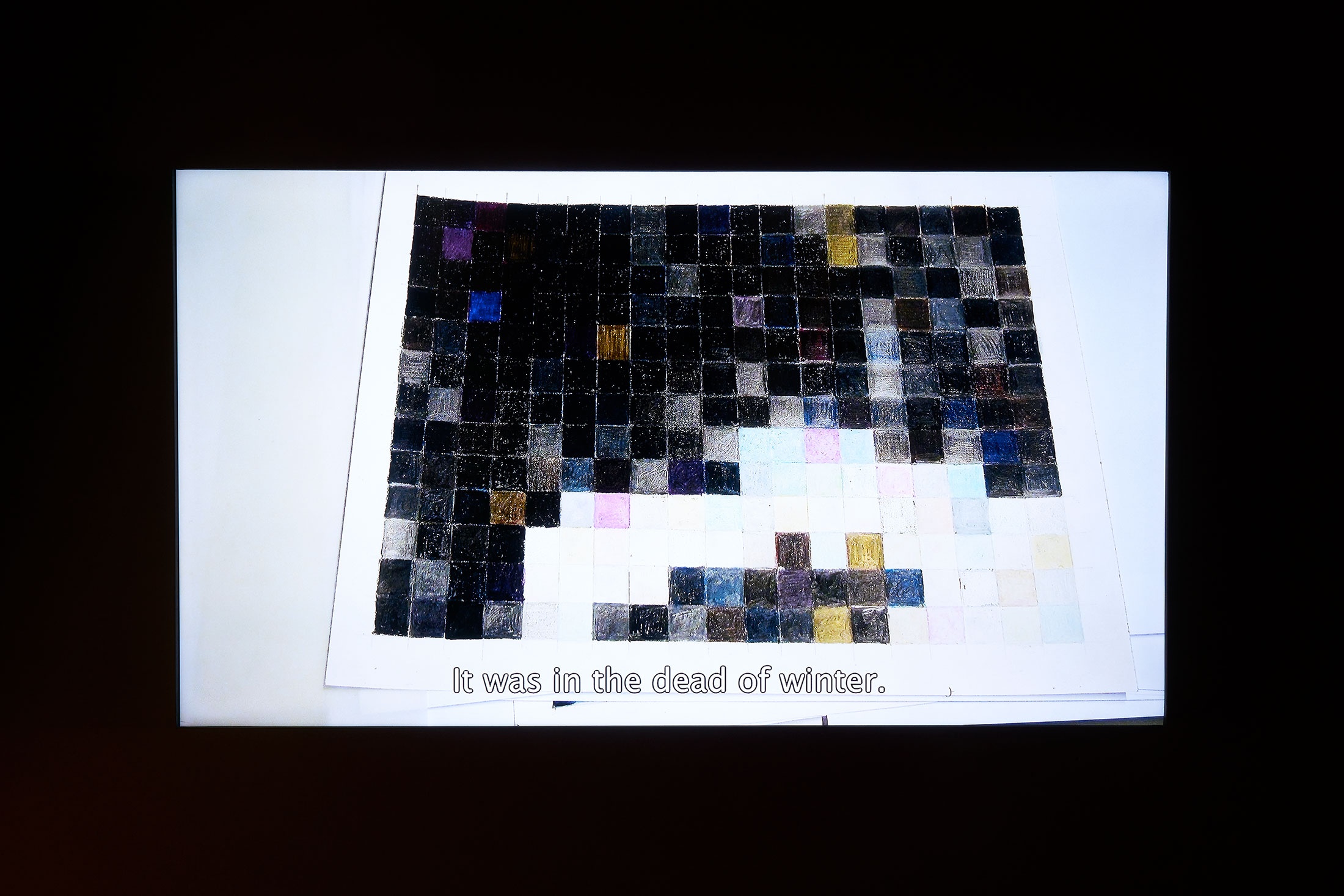

In Untitled (The City at Night), an unseen interlocutor asks after an anonymous artist’s archive of abstract drawings. Their paired voices are first heard in conversation against a dark screen, the artist recalling two incidents (one declared, one secret) that precipitated her withdrawal from the art world, and society at large, twenty years earlier. Since then, she has transcribed her nightly walks through the city, recounting her encounters with its nocturnal, marginal communities in geometric abstractions. She has no intention of showing her ‘scores’ – the name she has given the works – except for the small and exact amount of information shared in this film. Moreover, she has hidden her artwork behind another artwork (the artwork that is the film cast as a shield for her work, rather than as a method of exposure). To show the work is to undermine its conceptual potency. To this, the film pairs the interview with few images. A slideshow of the archive’s housing plays; its print cabinets, select drawers, and only a handful of discrete ‘scores’ are shared. This staid restraint is a counterpoint to the work’s final scene – the only moving image in the film and its only musical accompaniment. The camera plays the part of artist, traversing the night-time streets of Oslo, observing its inhabitants, its shuttered storefronts, its imperfect emptiness. Untitled (The City at Night) is a work of uncertain genre; social document, political fiction, or neither. With its ambivalent claim to truth, it offers an image of the artist as a figure of radical ethical potential on the periphery of late capitalism.

b.1971, Oslo

In text, film, and installation, Ane Hjort Guttu offers spare reflections on the potential of art to challenge political systems. The thematic fulcrum of her work is most eloquently distilled in her suite of four films – Freedom Requires Free People (2011), Untitled (The City at Night) (2013), This Place is Every Place (2014), and Time Passes (2015) – which takes as subject individual freedom within the body politic, the artist in society, and the representation of inequalities. The films’ refined simplicity, more often centred on a single action, belies the complexities of the artist’s concerns. They are neither didactic nor ideological, but rather suggestive and speculative; part documentary, part fiction. The conceit is apparent; the narratives only more compelling for it. A child rails against school rules, an artist makes drawings no one will ever see, activists look to the utopian future, an art student begs alongside an unhoused woman. All gesture to the respective powers of the implicit and the visible, to the political made apparent, and the political left unaccounted for. “I’ve decided that I don’t want to document or represent what I’ve done these past months,” one character says to another. “Because when I do so, I lose my work.”