Penny Siopis

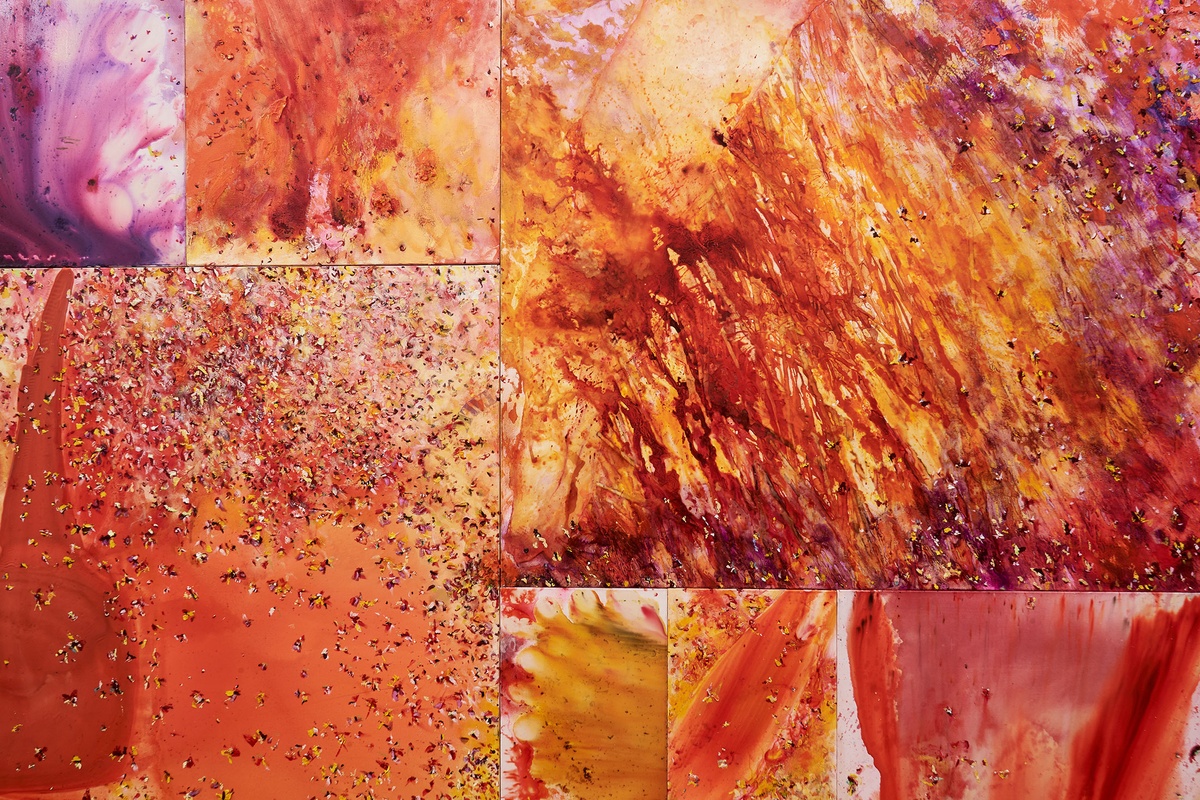

In 2017 Penny Siopis first took up residency in the Maitland Institute. The resulting project, Open Form/Open Studio, opened her practice to the public and shared her thinking about materiality. The giant glue and ink paintings created in the Institute’s warehouse evidence her process-focused approach. Speaking of this mode, she has said: “My method is to set the conditions for something to happen, and respond... The physical things that emerge from this material process are the objects we call paintings. I see these as residues of performance.” Through her engagement with materiality, she bears out her philosophy of relationality, describing viscous glue as acting like a “skin” when it dries, transforming from white substance to transparent layer after exposure to the air, and later, when stained, reacting to the chemistry of ink. Shapes emerge through this interaction and through the play of gravity (the canvas placed horizontally on the floor) and with the gestures of her body. “All these material acts resonate for me with wider philosophical concerns about opening oneself to the ‘life’ of matter and finding, in this openness, an intimate model for relationality in the bigger political picture of the self, the social body, ecology: a model that is full of risk and uncertainty.”

Reinhabiting the Maitland Institute in 2019, Siopis’ starting point was to gather certain of the canvases gleaned from her residency two years prior, together with earlier works, reincarnating them as elements of an immersive configuration. Imagined as mobile and moveable, the paintings-as-installation are site responsive, adapting to context and environment, much like her object installations. The edges of the canvas find one another, individual bodies tessellating to make the larger corpus. For Siopis, her medium is a partner rather than something she dominates. The artist’s instrument is her body, the bodies of ink, glue, and paint are players. Together, Siopis and her materials engage in an improvisatory choreography. Watching the documentary footage of the artist working at Maitland Institute, the physicality of her practice becomes apparent. In the film we see a fine, spare, delicately proportioned person, climbing onto an island of white canvas. Thus begins a dance in which she embraces, throws, and holds the giant frames. The artist closely observes glues and inks, watching where they rush, sit, fall, and pool, observing the circles and lines that emerge through “directed chance.” Prioritising use and reuse, these paintings were made by “using what’s to hand, rather than buying more things.” The phrases in them assemble words cut from newspaper articles from the time that reported on the climate crisis.

As an educator, through her time at the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Cape Town, Siopis is beloved for her horizontal approach, eschewing hierarchy for deep listening and attentive encouragement of her students. For the artist, everything is relational – is about relationships – her practice illuminating the place of touching, the space of ‘between’, which is where the work happens, finding its form. That the painting has dried is no indicator that an artwork is complete. Rather, each painting is a record of a process, and the conversation with matter that the artist is having on its surface can be reopened at any time.

Maitland Institute (2016–2020) was founded by Tammi Glick to be a fully-funded environment in which artists could experiment freely with their practices. The sincere, hopeful, and generous contribution that Glick made to the arts community in Cape Town is visible in the traces of the works that were created there, among these Penny Siopis’ Maitland paintings and Jared Ginsburg’s Hanging Drawings.

b.1953, Vryburg; works in Cape Town

In describing Penny Siopis’ practice, a necessary caveat: it is too slippery in form, too wide-ranging in ambition, to be distilled to pithy statement. Hers is an “aesthetic of accumulation,” a logic of excess, a hoarding of signs. Edges, boundary lines, beginnings and endings, states of change – these are among the subjects that inform her enquiries. As to a single preoccupation, the artist offers residue. A ‘historical materialist’, Siopis looks to the traces of past action, asks after the vibrancy of artefacts made and found, what they might recall of their provenance. She moves between modes with limber agility, playing the roles of both artist and archivist. While predominantly a painter, Siopis’ practice extends to include found film and objects in a sustained meditation on trauma as it appears, the artist writes, “in material amalgam.” From her early ‘history’ paintings to Will, a growing collection of objects and their anecdotes to be bequeathed to friends and family at the artist’s death, loss (past, forthcoming) is a constant undertone. Pursuing a “poetics of vulnerability”, Siopis transcribes, however obliquely, shared and individual griefs – punctuated by small moments of tactile transcendence – in the inherited images and historical flotsam, in the residue, with which she works.