Walter Battiss

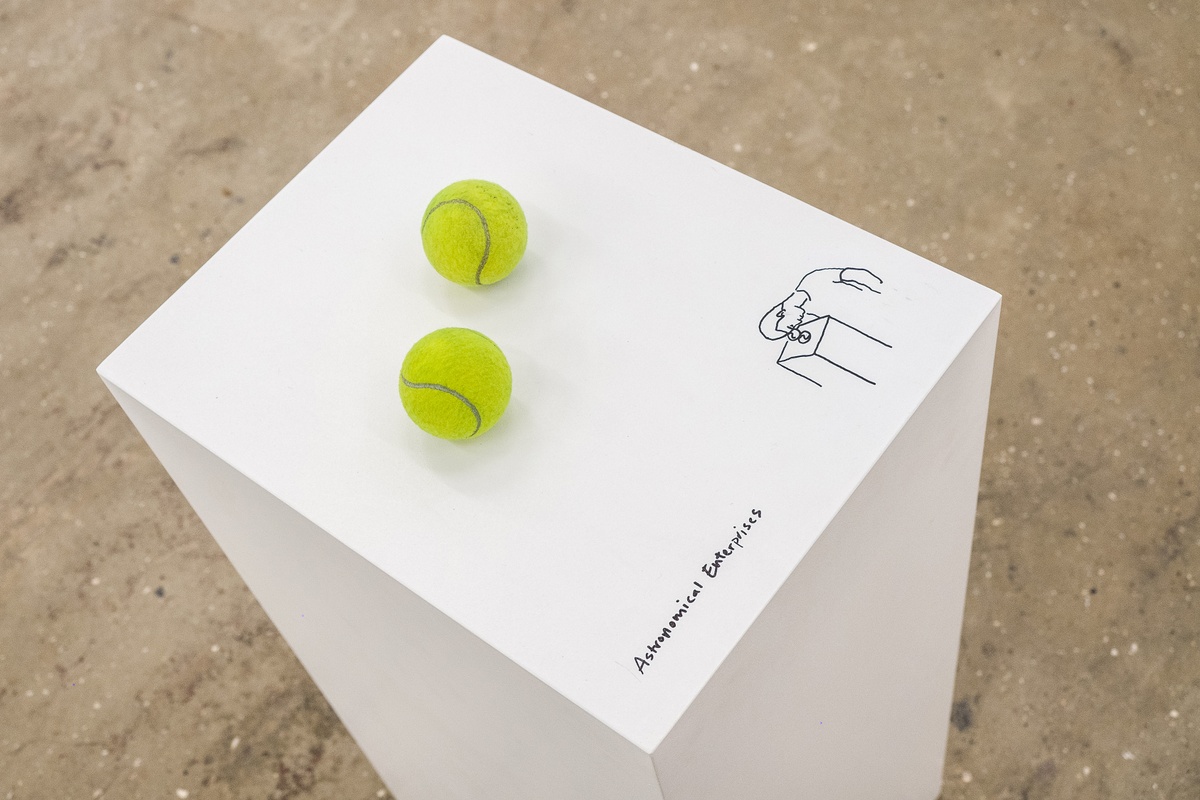

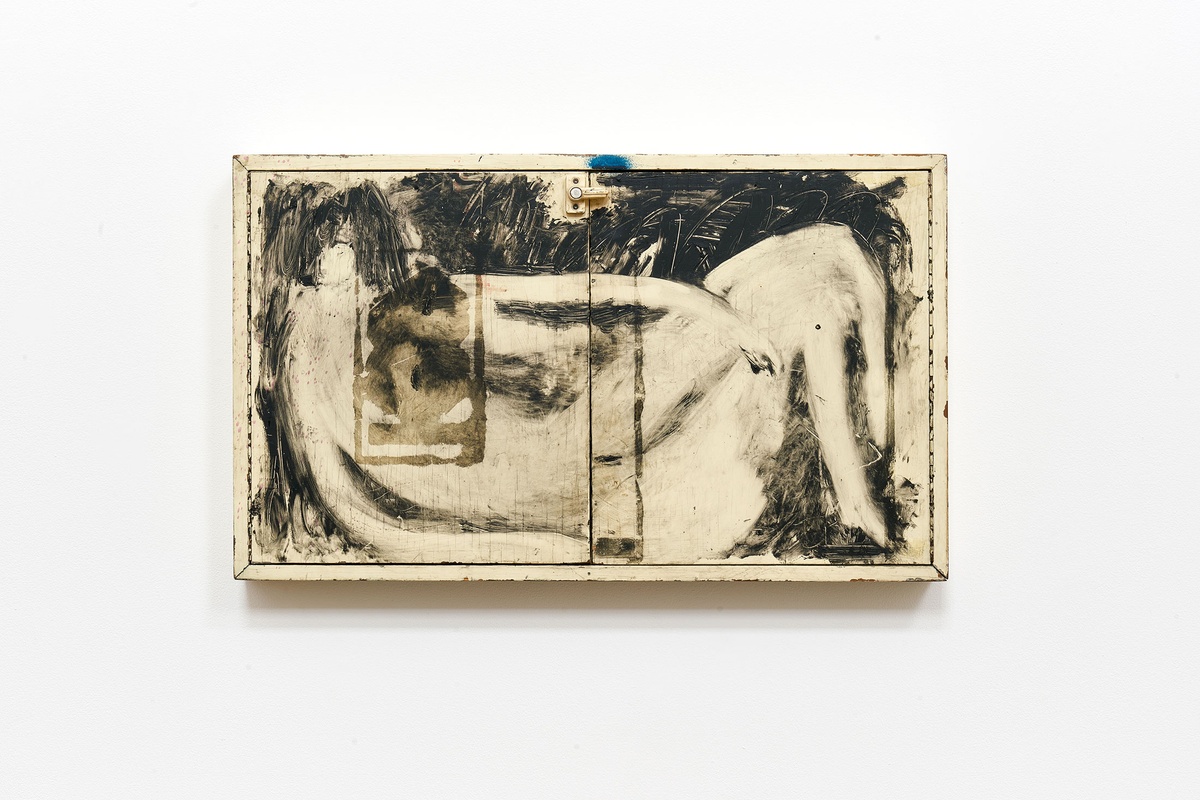

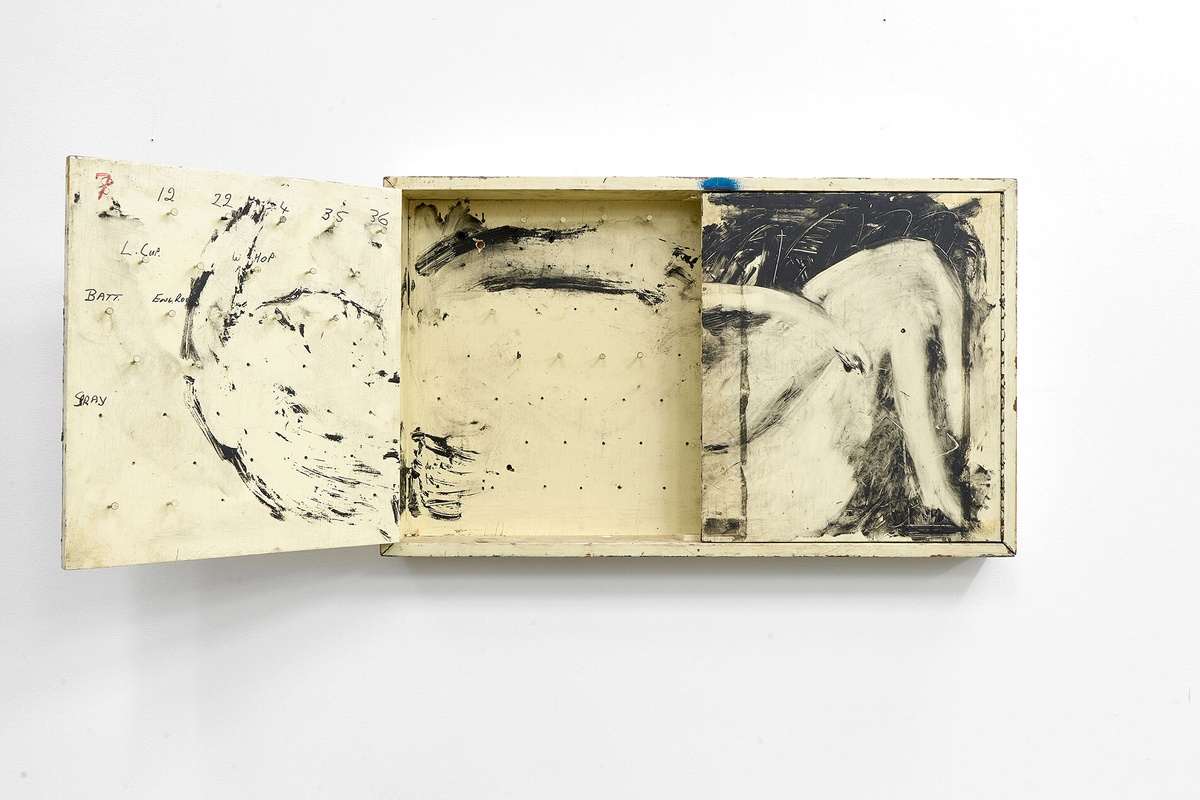

My Typewriter’s genre-bending form signals the beginning of Battiss's more conceptual pursuits.

My Typewriter was first shown at A4 in the exhibition More for Less (February 9–May 27, 2018), and later in Photo book! Photo-book! Photobook!, an exhibition curated by Sean O'Toole (February 11–May 21, 2022). In the latter, the artwork appeared alongside Battiss's contemporaneous photobook, Limpopo (1965). Together, these two works evinced the artist's limber engagement with medium and form in service of thought.

b.1906, KwaNojoli; d.1982, Port Shepstone

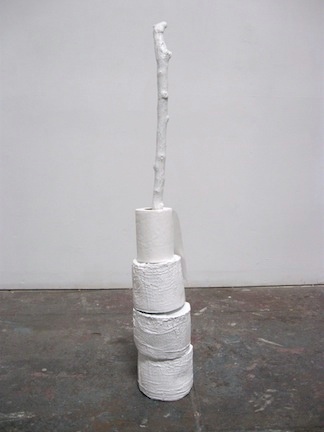

Walter Battiss remains an enduringly enigmatic figure in South African art history. He is notable for his inconstant and various mediums – including, among others, watercolour, oils, silkscreen, ceramics, and sculpture – and for the collision of influences in his work. In pursuing a new African modernism, Battiss experimented with such seemingly incongruent styles as Post-Impressionism and Pop Art, paired with formal elements borrowed from San rock paintings, Arabic calligraphy and Ndebele beadwork. While the artist described himself as the “first neo-primitive in South Africa”, others variously classed him a “gentle anarchist,” “amateur anthropologist,” “paunchy painter-poet,” and “wandering nude.” Battiss is remembered today as King Fern of Fook Island, a utopian, sub-tropical destination of his own imagining.