Iñaki Bonillas

Excerpt from a conversation with Iñaki Bonillas (I.B.), Josh Ginsburg (J.G.), and Francisco Berzunza (F.B.) held in person in preparation for the exhibition You to Me, Me to You, 5 June 2023:

I.B. In 2010, after my third show with Galería OMR in Mexico City, I suddenly had this feeling that it was a good time to make a homage to my father. In previous years, I had inherited several things that belonged to him. My father was a professional bullfighter in the 1960s. This is a rare practice, for a father – moreover, to then have inherited this ephemera, as a son. Among the memorabilia I inherited were some albums of photographs, news clippings, a couple of movies filmed on 16mm. These things spoke to me of someone I hadn’t really had a chance to meet. He died when I was five years old, so while I have a couple of personal memories, the rest have been collected from testimonies, and most I have had to build myself.

Part of being a bullfighter was that he was quite a skilled musician. He liked to improvise on the guitar and record those improvisations on cassettes. I felt it was quite curious that none of these materials I inherited were in their original formats. I was not hearing him play the guitar live, or inheriting a score of musical notations – just these cassettes that felt like they were at risk of being about to break. The news clippings were turning yellow and I didn’t have the printing plates to produce them, only this feeling that in a couple of years more, they would be taken over by this yellowing, erasing the words that I would not be able to read again. The negatives were also missing from the photographs, which had been stuck with bad-quality glue, the acid penetrating through the photograph. As for the VHS tapes, I had the same feeling about these as I did about the cassettes; that they would eventually be eaten by the machines they required to be played. Eventually, I felt I was doing an exercise of a ‘double return’ to the origin. I was trying to get back, to know and understand who my father had been to me, build up a lack of memory. When you don’t have a paternal figure you lack a paternal memory, and I had the opportunity to build this for myself. The documents were begging me to restore them, to bring them to the original state so that somehow, they could be endlessly reproduced.

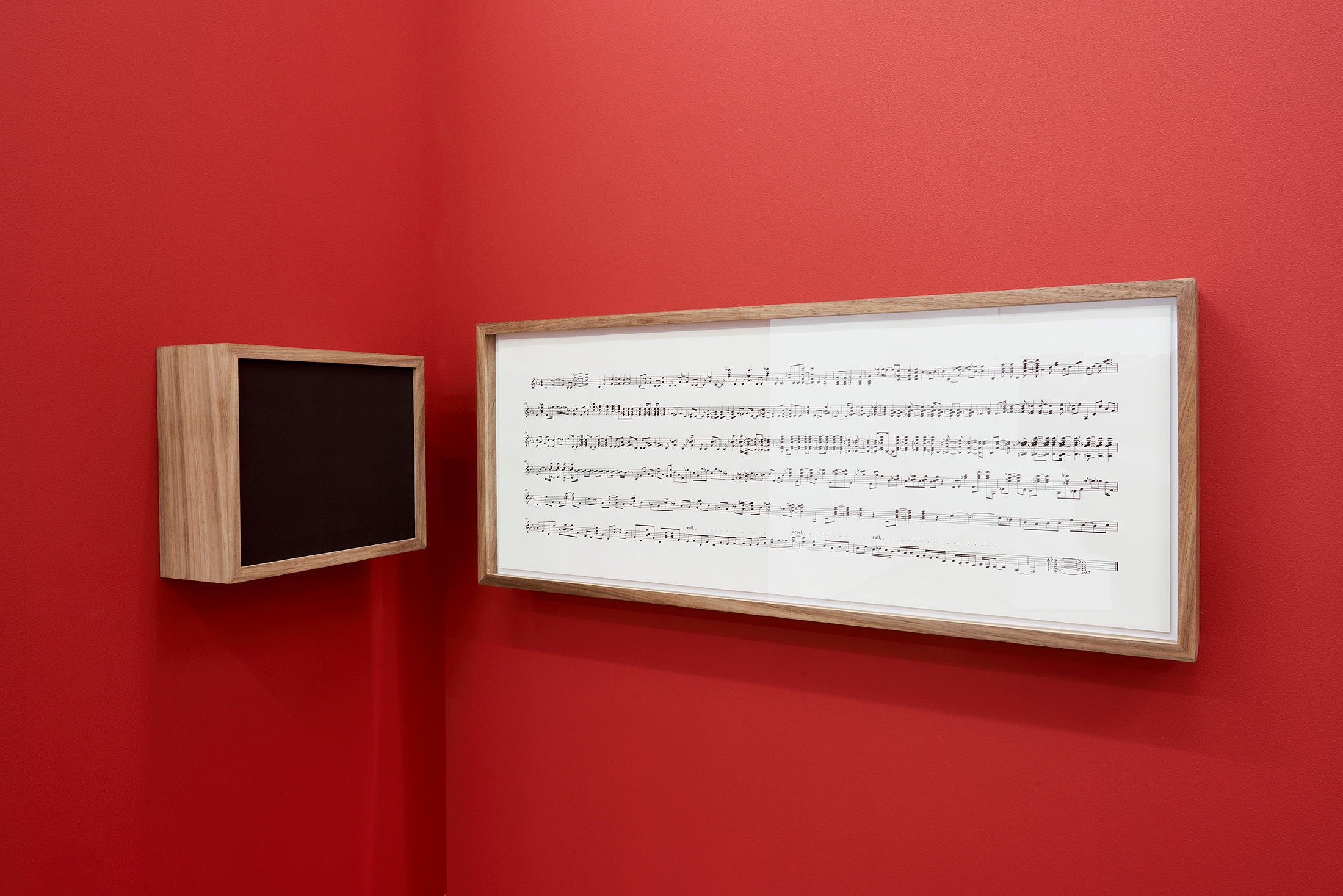

In The Return to the Origin, I basically returned to the origin of every document I had inherited. With the help of a musician, I was annotating each of the musical notes my father had improvised on the guitar. We built scores that could be played by anyone who could read music – we would always have the score. The same process of rewinding, or reversing back to the origin occurred with the photographs, and I retyped the paragraphs describing his more glorious achievements. The VHS film was reverse-engineered into a cinematic film. This ended up, coincidentally, being a project about the frontiers of the technical aspects of these material objects I had inherited, some of whose origins themselves were about to disappear, such as VHS, and cassette – these were on the cusp of having their production methods disappear, becoming the memory of the memory.

The works behaved as hinges that opened or closed the past.

J.G. Translation comes with loss, slippages, opportunities. You’re constructing these memories, not for them to be pure, but that they create an electrical circuit, close the loop, set the signal moving. Are you translating it or are you creating a condition where we experience it as neither this, nor that, or something in between?

I.B. I am always asking this of myself when working with memories that were begun by someone else, amplifying an echo, where is my voice located, here?

J.G. A perfect translation is reversible, like mathematics. Translation in language aspires to perfect reversibility but it is not. Your work, as the hinges that you described earlier, create a third, in between.

–

Upon his arrival at A4, Bonillas encountered that his work was intended for placement on a wall that had, at the curator’s request, been painted a vibrant red. At first, Bonillas found this choice disconcerting. Arriving at a resolve, three events occurred in quick succession. Bonillas, recalled that the red of the wall was the same as the dust jacket of Terry Kurgan’s narrative non-fiction work Everyone is Present (2018). Bonillas had encountered this book at Dashwood Books in New York City, the same year of the book’s publication. Kurgan’s book was one of Bonillas’s first encounters with South Africa and he was especially drawn to Kurgan’s material, her family photographic archive, and felt a kinship with her way of working. The photograph of the bench on the front cover of her book further reminded him of the bench Thomas Bernhard sits upon in the documentary Three Days (1970). Bernhard, particularly Bernhard’s dislike of translation, was modulated by Bonillas into a work that deals directly with translation – asking scribes who work at Plaza de Santo Domingo in Mexico City to copy Spanish as well as German versions of a Bernhard text, and the surprising results that arose through this exercise.

The second encounter occurred while Bonillas was exploring the works in A4’s Library (of which Kurgan’s is among that number.) He came across one of his own, long out of print, concerning one of the first project spaces the artist had founded in Mexico City. He had not seen this book in many years. To come across a copy in Cape Town at the foundation in which he found himself working towards the exhibition You to Me, Me to You created a moment of synchronicity for the artist.

Looking at the wall, it now appeared to Bonillas that The Return to the Origin was enclosed by the same red as a Toreador’s cape – the occupation of Bonillas’s father as he played the guitar melody we hear alongside its transcribed score.

b.1981, Mexico City

Iñaki Bonillas is attuned to the complexities and poetics of inheritances. As a teenager in Mexico City, Bonillas could be found in the company of artists twice his age, where he would spend long nights listening intently to their discussions about radical art. These gatherings became his education: in abstraction, in conceptualism. At times, the young Bonillas “wondered if they were making these artworks up – if they were making fun of me.” His experience was of a community of artists eager to share information and resources, whether these be books or stories of travel. From within this cohort of conceptual workers, he found his lineage, beginning to develop his practice. At the age of seventeen, Bonillas was included in a museum show by curator Guillermo Santamarina. Bonillas’s precocious offering – an installation consisting of the subtlest changes in light that, when isolated, became pronounced – attracted the attention of Galería OMR, the first gallery to take seriously the work of contemporary artists in Mexico. Since this time, the artist has turned his attention to the material traces inherited from his father and grandfather, engaged in a modulation that the artist likens to “amplifying an echo.” Referring to Bonillas’s practice, Josh Ginsburg says, “There is a point where the copy is so impossible it cannot be a copy at all, where the translation renders anew.”