James Webb

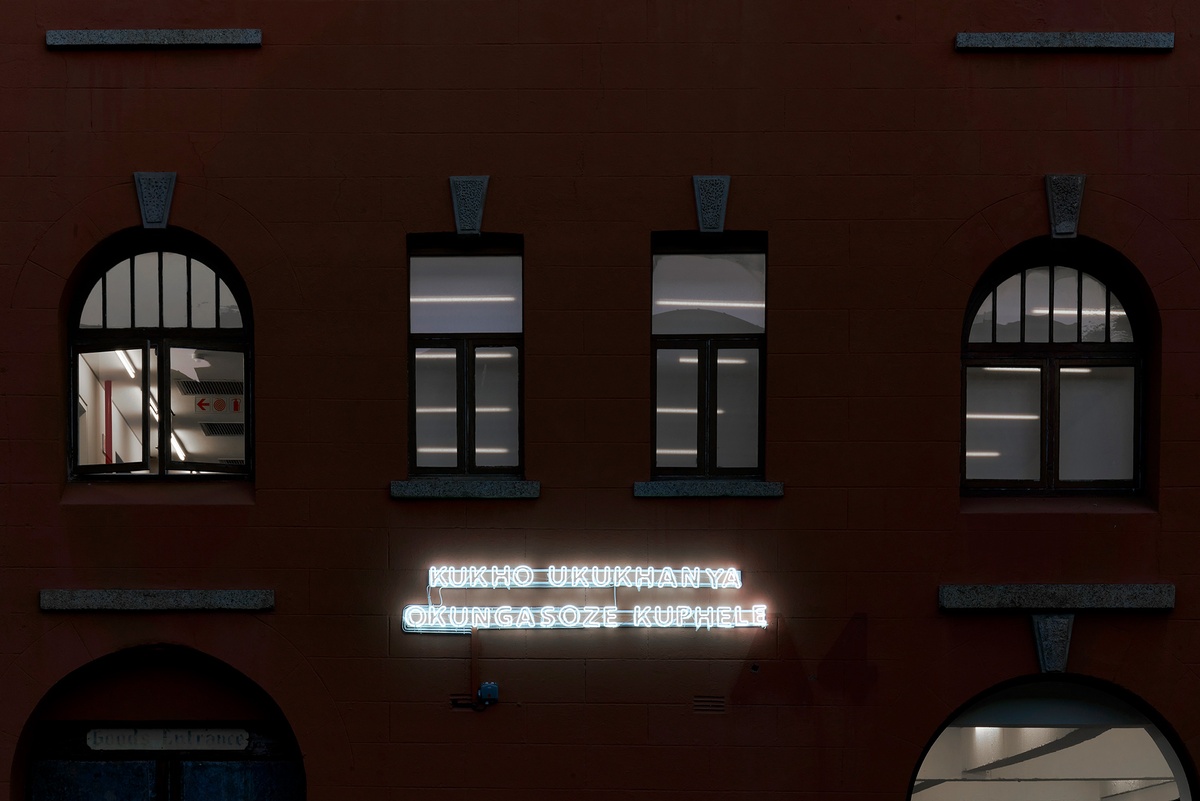

Titled after a 1986 song by The Smiths, There Is A Light That Never Goes Out (isiXhosa) extends a conceptual circularity: illuminated, the white neon words become the light they speak of. In each modulation of the piece, the phrase is translated into the vernacular of its intended location – the cultural nuances of differing geographies offering variable interpretations of its phrase. “Translation is a process of something getting lost and something getting found; there is a transformation in translation,” says the artist. The first of the works, written in Arabic, was conceived for Moroccan curator Abdellah Karroum’s exhibition, Sentences on the banks and other activities. When There Is A Light That Never Goes Out (Mixe) appeared in Hacer Noche, curated by Francisco Berzunza in Oaxaca in 2018, it was interpreted as a statement of solidarity with efforts to conserve the language – that it will never die out. There Is A Light That Never Goes Out (isiXhosa) sees the phrase translated into isiXhosa – one of South Africa’s eleven official languages – to read, “Kukho ukukhanya okunga soze kuphele.” Including the work in You to Me, Me to You brings the exhibition onto the street, where it may be experienced incidentally – in passing. On the facade of A4, There Is A Light That Never Goes Out (isiXhosa) faces the Magistrate’s Court. Opposite the Court, Cape Town’s Central Police Station; alongside The District Six Museum. Webb remains most interested in how the work’s location may alter its interpretations.

b.1975, Kimberley

There is in James Webb's work a gestural eloquence in form and thought, a distillation of idea akin to haiku. While his primary medium is sound, the artist suggests that “listening and doing nothing” perhaps better describes his preoccupations. “Listening,” Webb says, “is a very hard thing to do. It’s about paying attention, and being open to the unknown.” Indeed, he is no stranger to the unknown, inviting such themes as the occult and spiritualism into his work. Attuned to the poetics of the ordinary and understated, his work draws attention to the numinous in the normal. With objects minimal and more often monochrome, Webb lends to his sounds a material housing. Some he allows to exist as only aural offerings – birds calling from trees, voices singing under bridges. Few remain silent yet are all the more compelling for their quiet. An unseen stranger coughs in the gallery, a voice directs a series of questions to five litres of Nigerian crude oil – “What do you remember of prehistoric sunlight?” – a microphone records its journey to the bottom of a mine shaft, a broken clock becomes obscure religious symbol.