Kudzanai Chiurai

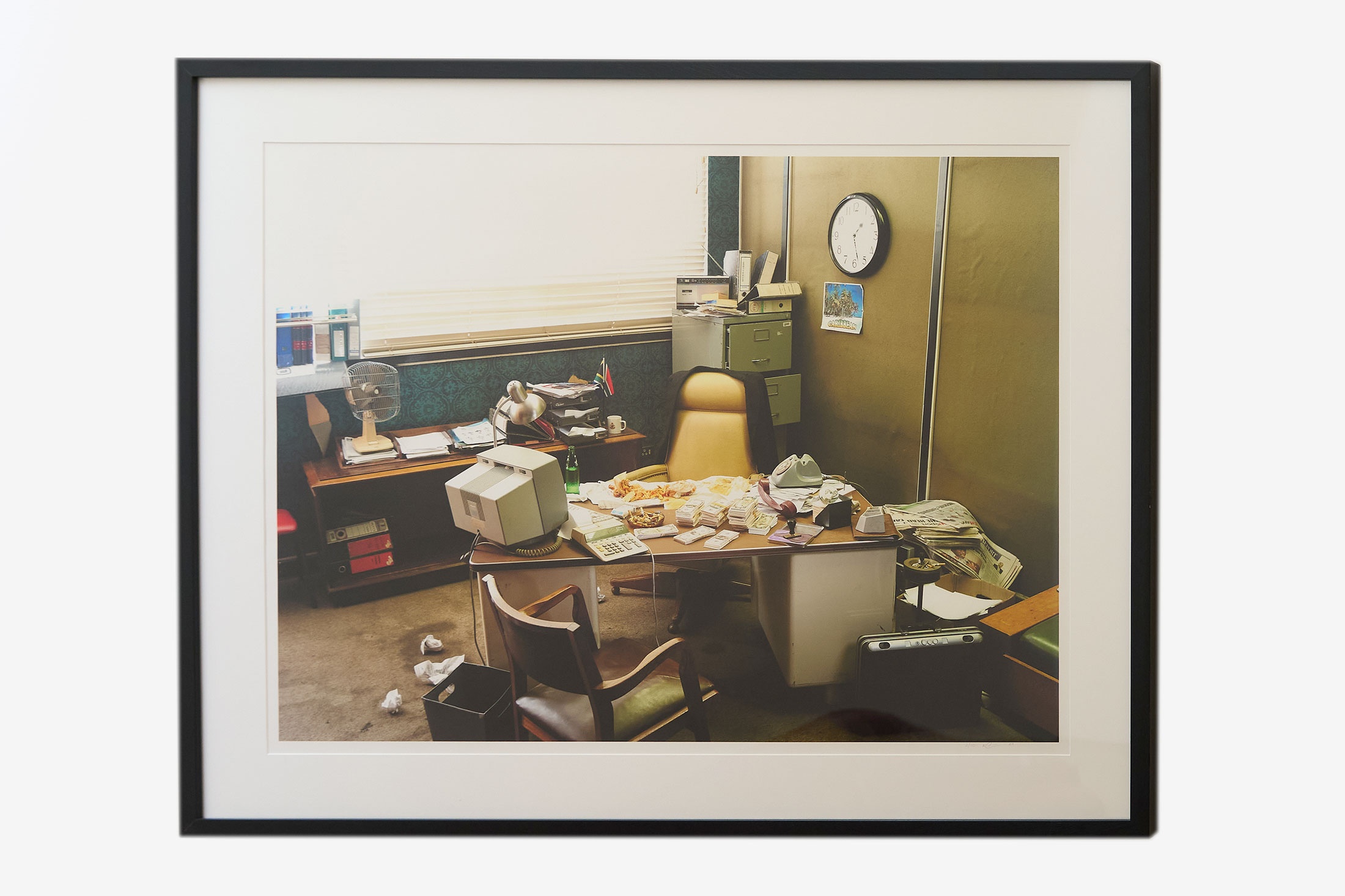

Appearing as stage sets, Chiurai’s triptych of photographs, Untitled (I), (II), and (III), imagine the life of a corrupt bureaucrat and the work performed (or un-performed) within their office space. Describing the series in an interview published by Artthrob, the artist summarises the narrative suggested by the photographs:

They represent three different times of the day. The first one is early in the morning. Then by lunchtime, he has all of that money on the table, and slap chips and bread, a cigarette lit… A whole mess. Then in the last one, it’s three o’clock, and he’s knocked off, and he’s not in the office. There’s a glass of whiskey and a G-string on the couch. If you look to the right of his chair, there’s a poster of paradise – I think it’s a holiday to the Caribbean. It’s the smaller things; his phone and his computer are outdated. If you go to Home Affairs, some of the offices actually do look like that.

Read as political satire, the series lampoons the culture of machismo and corruption that is all too real in Southern Africa. Headlines of ‘tender-preneurship’ are omnipresent in the news, but the mechanisms that guide political corruption remain abstract to the general public. Like politics, A4 curator Khanya Mashabela suggests, the art market is similarly perceived as relying on the soft powers of networking and ‘handshake’ deals. For those who find the art world’s walls to be impenetrable, there is the perception of cronyism and more subtle or aestheticised forms of corruption. Included in WORK, a process project at A4 that enquired after work performed as recalled in the traces generated by it, Chiurai’s Untitled (II) serves to highlight how power relations are conveyed by objects in the broader political context and perhaps – more obliquely – in art economies.

b.1981, Harare

In an expansive practice that engages artistic, activist and archival strategies, Kudzanai Chiurai considers the continent and its discontents, and asks after the “paradox of virtue” that has come to characterise many ‘post-liberation’ African governments. “I think this has been the fundamental idea, that we are in fact living in post-colonial societies,” Chiurai says. “I doubt that we are in that situation at all. For me, we live in colonial futures. This is what we are grappling with.” His commentary finds form in theatrical photographic and video works, expressionistic paintings, and prints that riff on the declarative language and symbols of political posters. The artist’s criticisms, however, have not been without their price. In 2008, Chiurai was cast an enemy of Mugabe’s government. For a period, he left Zimbabwe for South Africa following repeated threats. This experience, rather than dissuade him, only galvanised his efforts. Mechanisms of political dissent and submission, the corrupting effect of power and the legacy of imperialism remain his guiding themes. “If we could write our history and chart our futures as we please,” Chiurai asks, “who would we be?”