William Kentridge

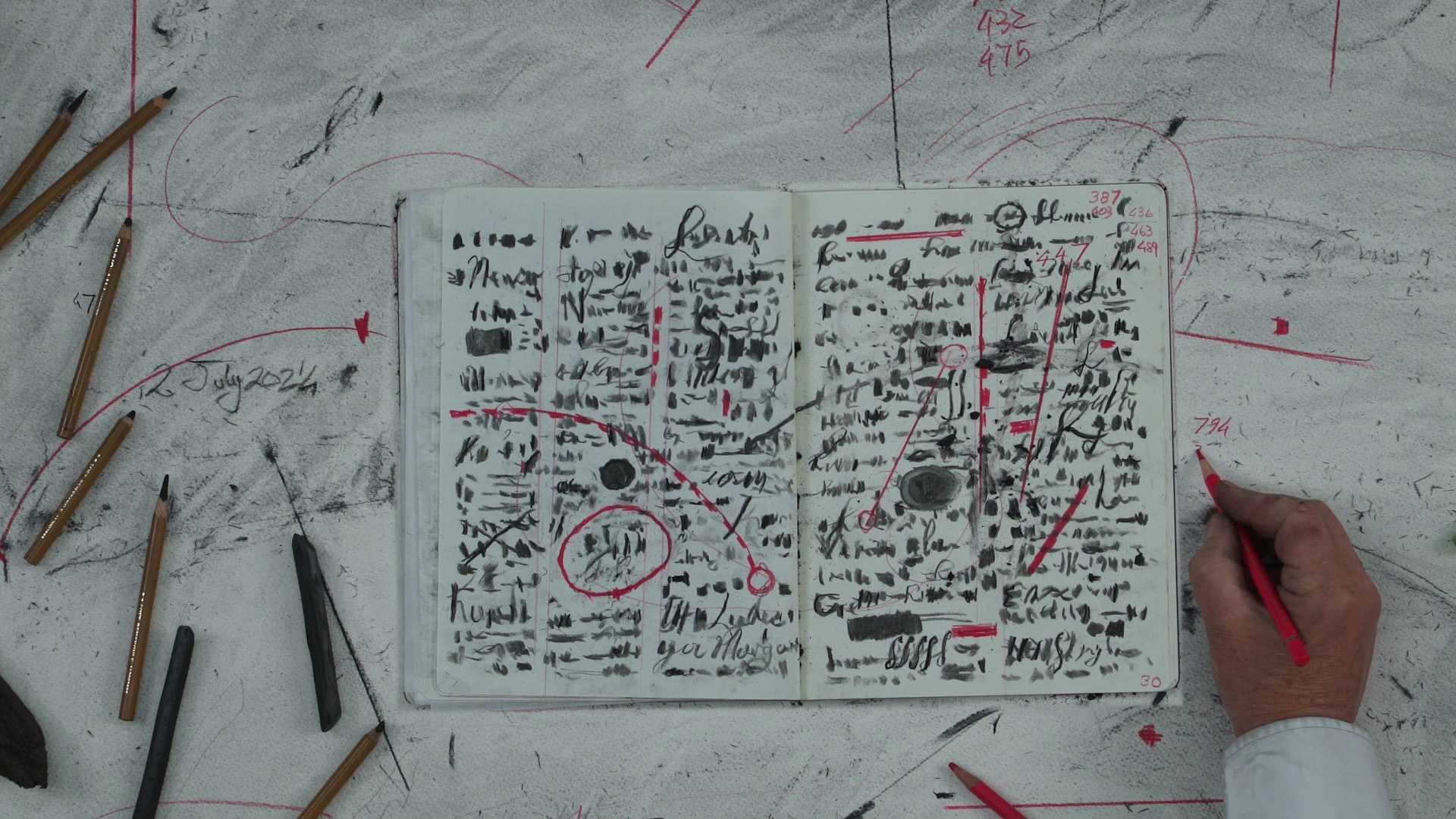

Fugitive Words premiers in History on One Leg. A video work staged entirely in one notebook, its drawings, incidents of figures, text and glyphs play out between the twinned frames of the bound pages set on a studio desk. A browsable copy of notebook no. 29 is included in the exhibition.

In the opening sequence, the artist’s hands page through a working notebook, with its to-do lists, timelines, ‘obligations’ (among them ‘drawing for A4’), and sketches towards sculptures. This overture sets the scene for an elliptical, non-narrative engagement with the book as an aide memoire that extends beyond the purely practical, a site where ‘fugitive’ words and images – free-floating, unbidden – find chance proximity between its covers. Seemingly unrelated phrases appear; impressions of a tree recur; portraits of the artist and others come and go; a wandering line journeys across the pages; marks feint towards, but seldom resolve into, writing. Even the artist’s drawing tools assume the role of characters, participants in the oblique logic of the notebook, around which eraser filings and charcoal dust notate a series of accumulations and erasures.

“Remove not the old landscape,” a cursive heading in Fugitive Words reads; “Enter not into the fields of the fatherless,” reads another. On a page dated 31 July, in a letter to his father, Kentridge asks: “What will remain when you are gone?” In Latin script, the words AVE ATQUE VALE appear – hail and farewell. Taken together, the coincidence of phrases assumes a tone elegiac and lamenting in a reflection on past loss and anticipated mourning. Included among the figures that populate the film’s pages are the artist’s late mother, Felicia, pictured as a young woman, and his father, Sydney, now 102. There is then the artist’s own likeness, which looks towards his ageing parent across the notebook’s binding. A supporting cast of Russian poet Mayakovsky and his lover, author Lilya Brik, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, and Surrealist André Breton cite two recent projects from Kentridge’s studio and the dissolution of revolutionary ambition. The woman from Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) also appears as does a nameless figure seen lying in a spreading pool of blood – a victim of South Africa’s political repression, perhaps – before being subsumed in the landscape.

For Kentridge, drawing in charcoal has long offered an analogue to thinking in its immediacy and provisionality. His animations, which most often extend from such drawings, proceed not from a predetermined storyline but “from an impulse, from an image that’s in my head, from something, a phrase, a central idea,” as Kentridge said in 20141. Scenes and words address themselves to the artist, are read or recalled, setting an unfolding sequence of associations, asides, indecisions, and revisions in motion. Sense-making is suspended in favour of uncertainty. Fragments coalesce and then disperse, speaking to one another in different registers: directly, tenuously. It is only in the doing – and in hindsight – that a given film’s themes and resonances become clear. To this, many of Kentridge’s video works and lectures recast the studio as a mind, a place where passing thoughts find form, however tentative; the semblance of sense composed from disparate parts. Here, the notebook, as an extension of the studio and its labours, plays a corresponding role.

1 William Kentridge Interview: How We Make Sense of the World, Louisiana Channel, 2014, available online (edited).

b.1955, Johannesburg

Performing the character of the artist working on the stage (in the world) of the studio, William Kentridge centres art-making as primary action, preoccupation, and plot. Appearing across mediums as his own best actor, he draws an autobiography in walks across pages of notebooks, megaphones shouting poetry as propaganda, making a song and dance in his studio as chief conjuror in a creative play. Looking at his work, a ceaseless output and extraordinary contribution to the South African cultural landscape, one finds a repetition of people, places and histories: the city of Johannesburg, a white stinkwood tree in the garden of his childhood home (one of two planted when he was nine years old), his father (Sir Sydney Kentridge) and mother (Felicia Kentridge), both of whom contributed greatly to the dissolution of apartheid as lawyers and activists. The Kentridge home, where the artist still lives today, was populated in his childhood by his parents’ artist friends and political collaborators, a milieu that proved formative in his ongoing engagement with world histories of expansionism and oppression throughout the 20th century. Parallel to – or rather, entangled with – these reflections is an enquiry into art historical movements, particularly those that press language to unexpected ends, such as Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism.

Moving dextrously from the particular and personal to the global political terrain, Kentridge returns to metabolise these findings in the working home of the artist’s studio, where the practitioner is staged as a public figure making visible his modes of investigation. Celebrated as a leading artist of the 21st century, Kentridge is the artistic director of operas and orchestras, from Sydney to London to Paris to New York to Cape Town, known for his collaborative way of working that prioritises thinking together with fellow practitioners skilled in their disciplines (for example, as composers, as dancers). Most often, he is someone who draws, in charcoal, in pencil and pencil crayon, in ink, the gestures and mark-making assured. In a collection of books for which A4 acted as custodian during the exhibition History on One Leg, one finds 200 publications devoted to Kentridge’s practice. In the end, he has said, the work that emerges is who you are.