Project text:

Kathryn Smith

Collaborator:

Alana Blignaut

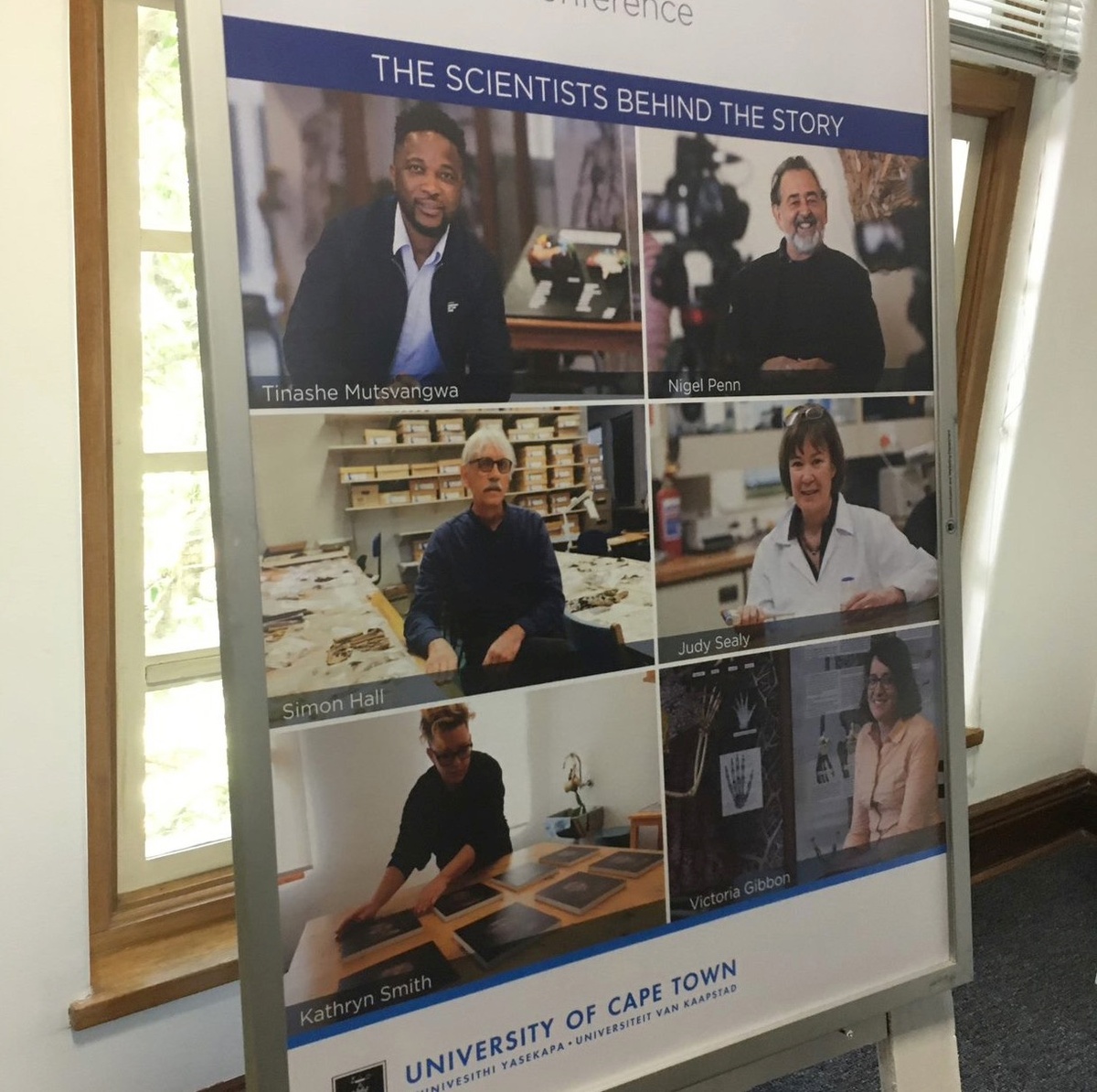

My time at A4 gave me precious mental and physical space and essential resources to focus on the final delivery of the #UCTSutherlandReburial project, as well as one other aspect of my current PhD project (on post-mortem representation within forensic cultures more generally), as I began to consolidate three years of research and fieldwork towards a final thesis.

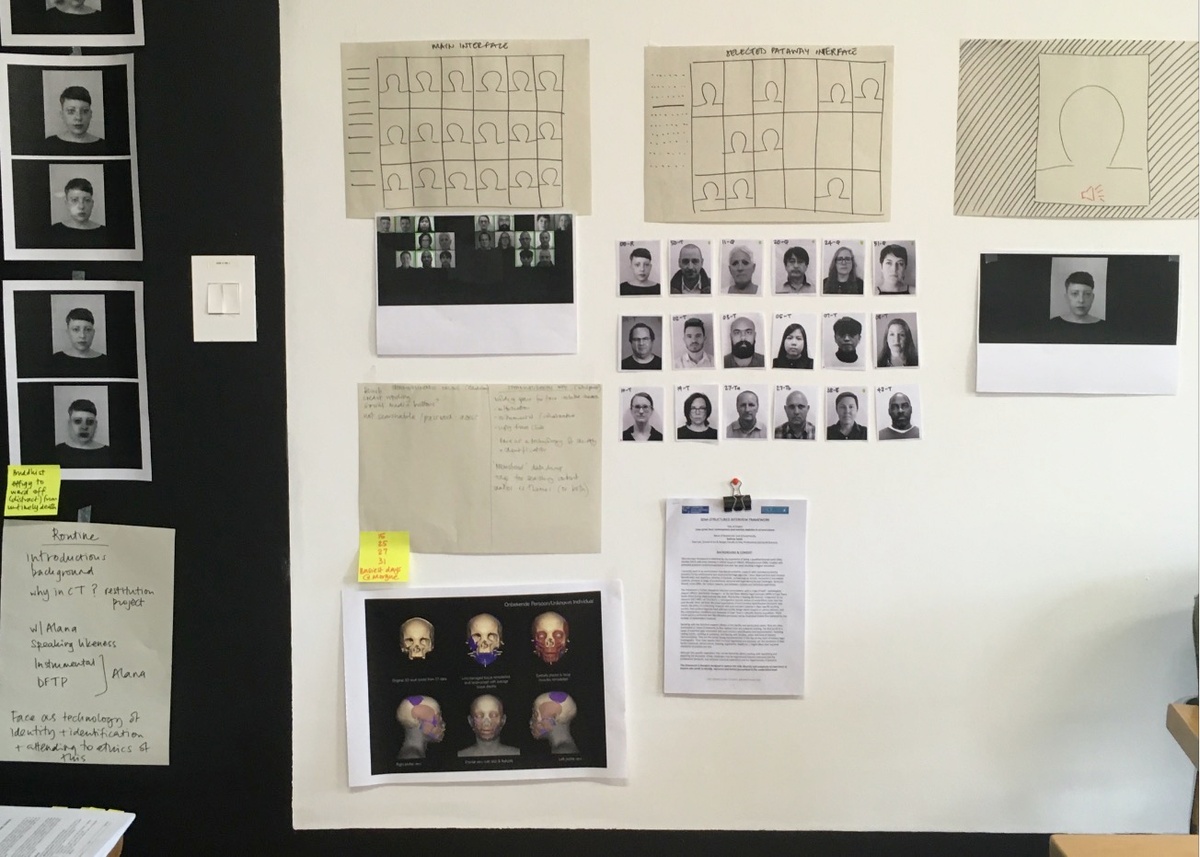

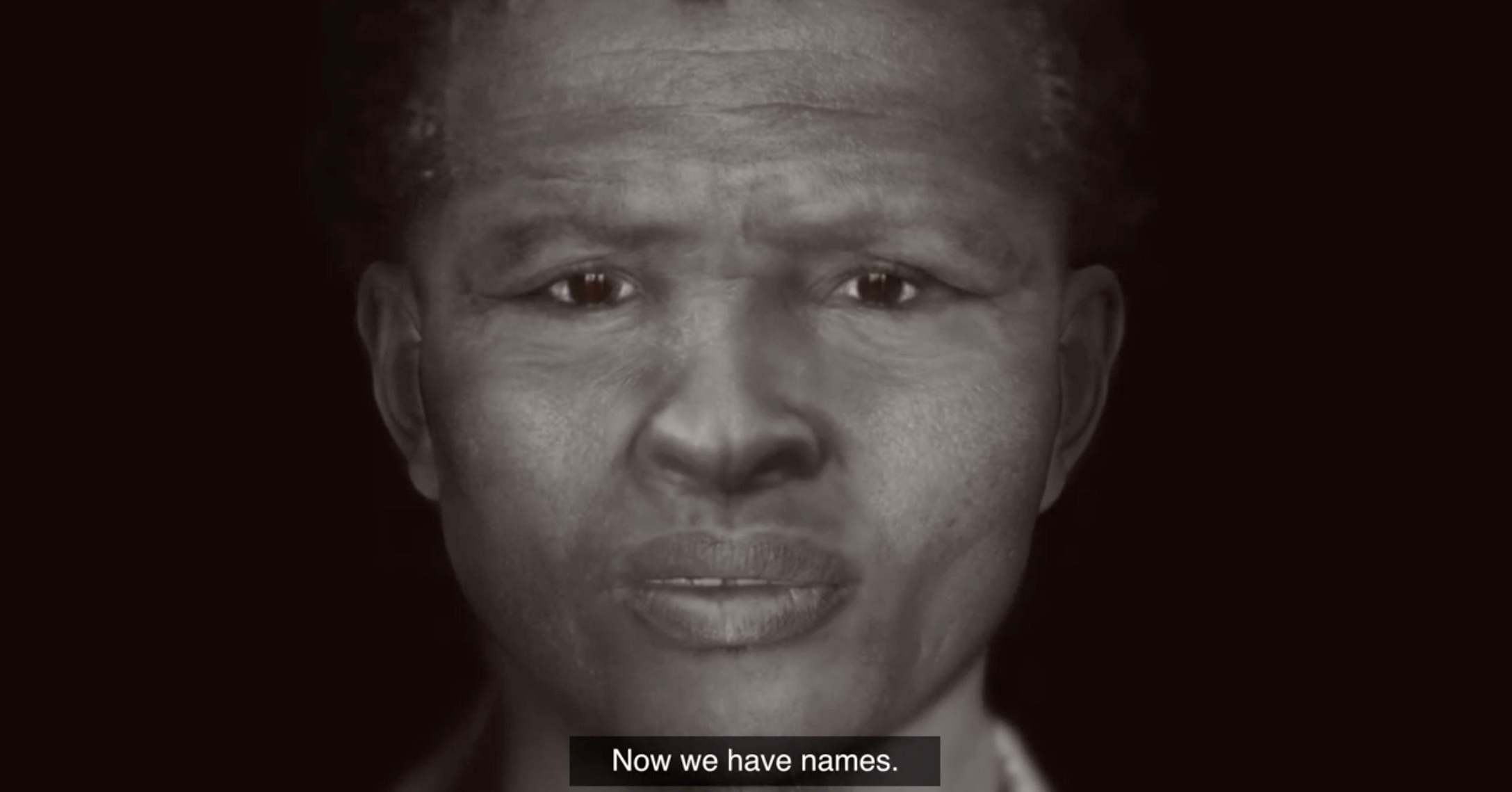

My main focus whilst at A4 was developing an audio-visual interpretation of some of my research interviews conducted with forensic artists around the world. These interviews were designed to draw out some of the less visible aspects of the role and function of the forensic artist – its emotional labours were a key interest. I was also interested in other aspects of visibility in this work. Forensic artists, particularly those working within law enforcement agencies, are seldom seen or named in relation to their work. Yet the images they make are critically tied to naming and visibility: they are often the final chance in getting a victim or suspected offender identified in relation to a crime.

Each artist who responded to my research questions was also asked to sit for a video portrait. This meant five minutes alone in a room, looking back into a camera. I explained my interest in returning the gaze of those tasked with producing facial images for forensic identification, but also that I was interested in what it is to be turned into the kind of image we are tasked with making. And then framing these images with personal reflections on how each person came to be doing this work.

The process of sitting still and holding a gaze inevitably records the moment when external awareness turns inwards. The resulting images appear still, but tiny gestures – blinking, breathing, swallowing – reveal the passing of real time as they stare back at us.

The process also demanded another conversation about visibility: for personal or professional reasons, the retention of anonymity was a condition of participation for some. But it was also essential that the link between word and image, key ciphers of ‘self’, was kept intact even as other features – the nuances of accent and tone of individual voice, for instance – would be lost. So their words are now spoken in my voice, staging the researcher as interlocutor, as medium.

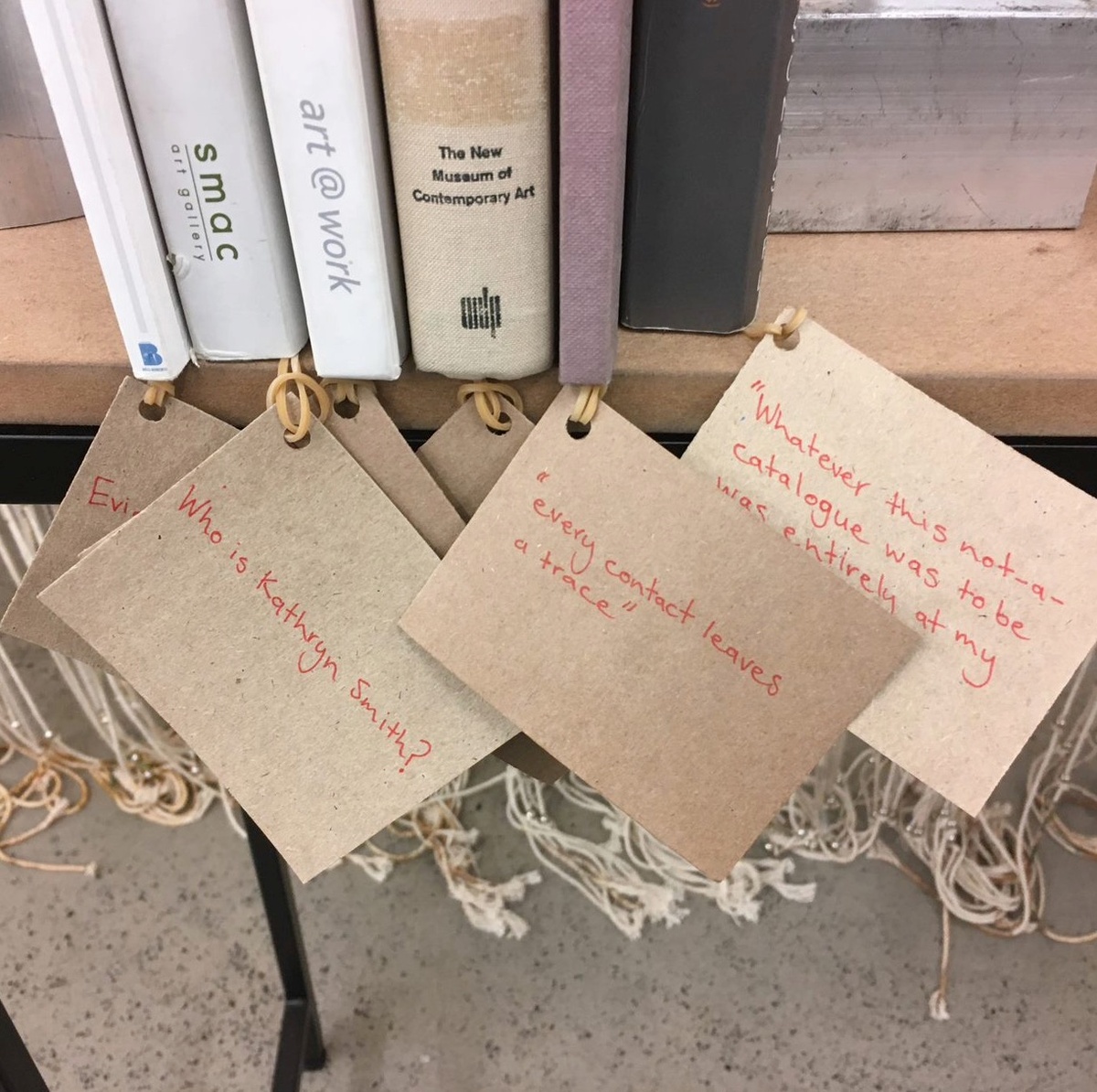

The work was conceived as an artistic conversation with a project by photographer Arne Svenson called Unspeaking Likeness (published in book form in 2016), where Svenson photographed forensic sculptures as if live subjects sitting for their portraits. His subjects cannot speak but exist because the people they are intended to represent have died without a name; they are a complex medium directed at recognition and identification.

My series of portraits, by contrast, is called Speaking Likeness. It features eighteen forensic artists from South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, South Korea and Japan.

I am not sure I managed to capture any of the artists whose work Svenson photographed. I do know one artist who sat for me declined his invitation to photograph her work. But as this work is designed as an ongoing project, perhaps these two projects can become more directly entangled.

Speaking Likeness is designed as an online piece, which a visitor will navigate via a series of thematic pathways (e.g. ‘It all started with...’; ‘The Names We Give’; 'There was this case...', ‘Matters of Care, Matters of Concern’; ‘Being Seen’ and so on). Selecting one theme brings up a virtual Lightbox of portraits of ‘active speakers’ for a particular theme. Clicking on each portrait activates the full-screen version of the narrated portrait. Once complete, it returns to the main menu, and you can navigate to the next theme, or replay the portraits as you wish.

During the residency, I worked with Alana Blignaut on the initial build of the site, and editing of the video elements in preparation for the audio voice-overs currently being scripted and recorded. As it forms part of my PhD submission, access will be password-protected until examination is complete, and to allow participants the right to withdraw (as per ethical guidelines) until that point. The hope is that it can be scaled up as a gallery-based installation, with each portrait on its own screen, staged as a piece of forensic theatre.

Having Alana at A4 was also an opportunity to showcase her work Desire for the Public, which was modified for a single screen and installed in the library. We hosted an informal ‘interface’ on a Saturday morning, opening up our respective practices and current projects in a library-based conversation. Along with our Routine session, presented to the A4 team and invited guests, these encounters were useful in revisiting a ‘failed’ project called Instrumental. We spent time taking the project apart and reconsidering its various components. For now, it has become two discrete objects: an interactive tool called Face Theremin, which uses face-tracking to generate electronic tones based on a user’s changing facial expressions; and an online repository for our ongoing collaborative research into the human face as a technology of identity and identification which is, for now, hosted at www.speakinglikeness.online.