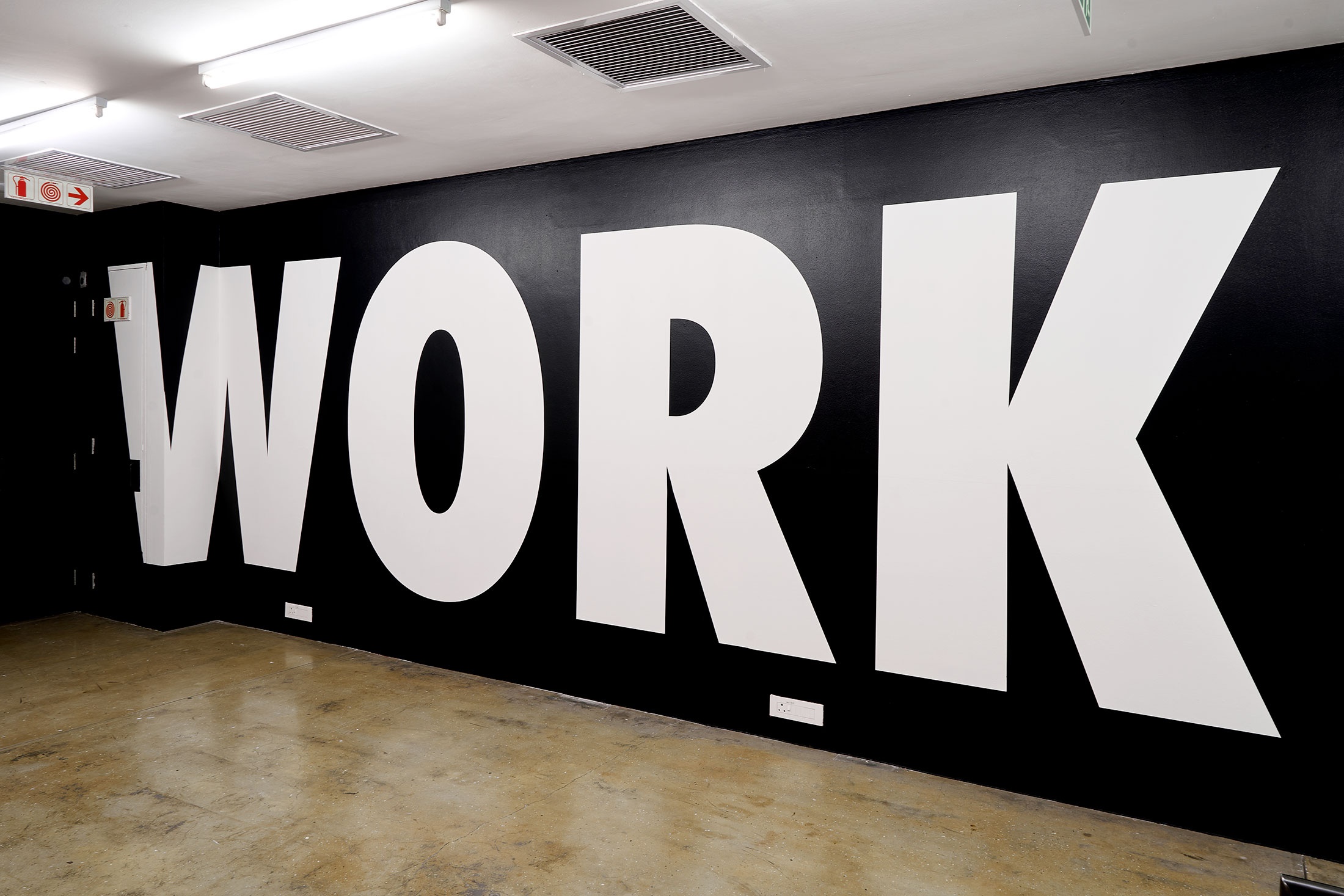

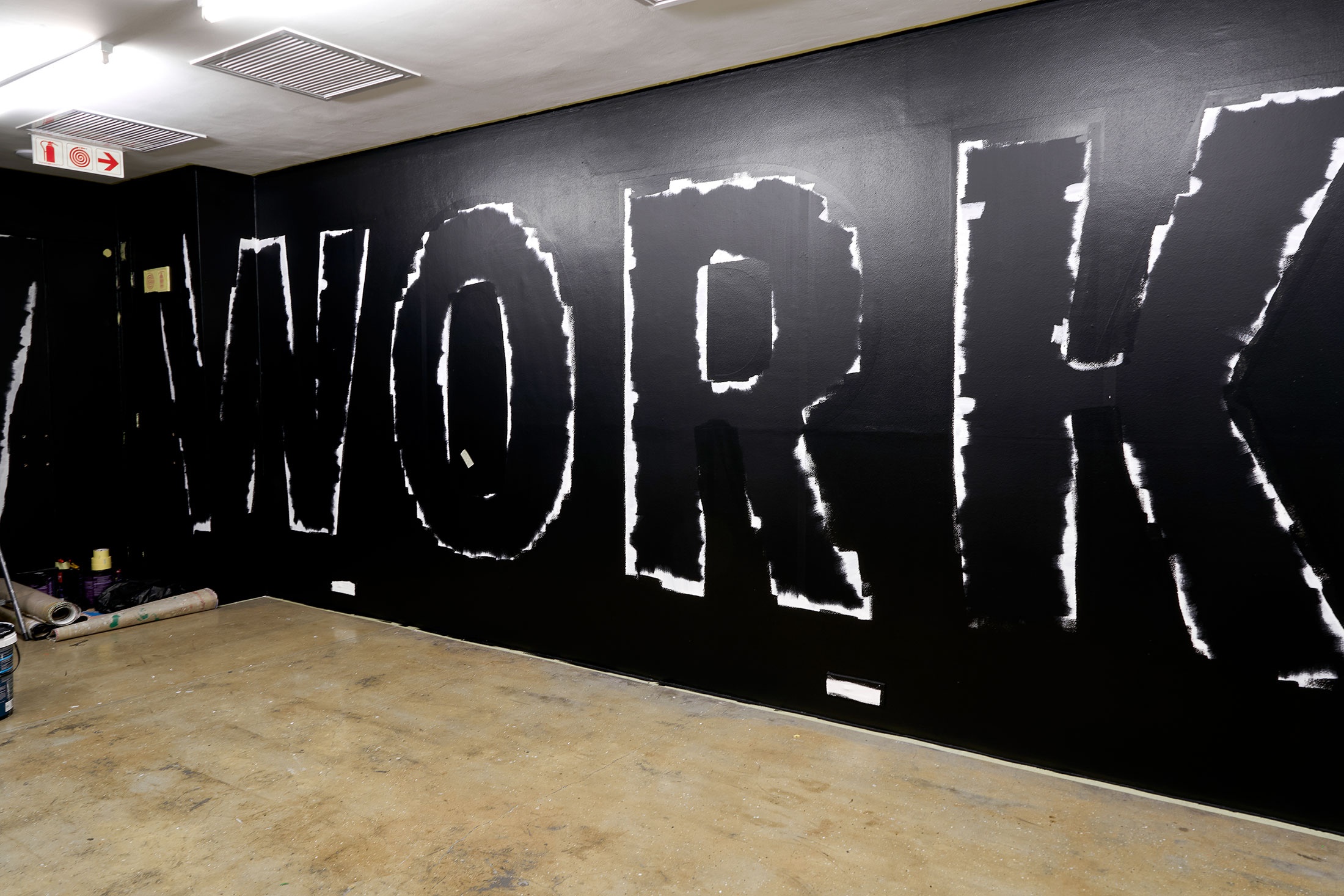

J.G. I LOVE NEW WORK was an opening gambit for the current project, WORK, in our Gallery. There was a question as to what ‘work’ looked like at A4 – what does a creative institution’s labour look and feel like? We wondered if we could bring this exploration into conversation for the interest of our community and audience, and also for ourselves.

You can quite quickly end up sitting behind a computer all day, chomping away at something, but we have other forms of work that need time and attention that are perhaps not accounted for. Reading as work, looking at artworks or watching video art as work. Is discussion work? What exactly is work?

So, I LOVE NEW WORK offered a way to kickstart the conversation. What happened, where does it come from?

E.Y. It was silly. I'm trying to remember now… I think it had something to do with Christian Nerf 1. We were travelling to New York in about 2008, and I sent him a message, and the predictive text changed it to ‘we're going to new work’ – that kind of thing. Christian made up a little mockup just for fun that said ‘I love new work’. I stole it from him and turned it into a ‘thing’. At the time we were doing a lot of collaboration and stealing. It was around then that I was doing murals, or trying to do more… I mean, I still am. It just came up – there were a few projects that required wall paintings, so it went to a few places.

J.G. I LOVE NEW WORK specifically, or your wall murals at the time?

E.Y. I LOVE NEW WORK. It’s moved around quite a bit.

It’s quite ironic that for WORK we’ve used an old work.

J.G. What were you guys doing in the States together, you and Christian?

E.Y. We had all these very ambitious projects, like No Problem in Africa. It started with this Dutch curator – he had this mad project where he just went around the world and met a lot of people and then said OK, you two from South Africa go there. Find stuff and find people. So Christian and I travelled together. We started making a lot of connections, doing talks and collaborations. And then I think there was the Africa pavilion or something at the Venice Biennale –

K.M. That's the iteration that got slammed by all the curators –

E.Y. Yeah, so we decided to go to make a pitch for it, because we had done all this really intense research, finding artists who are not in European collections. We thought we’d pitch ‘off-the-radar’ artists that we had met and engaged with. We decided to fly up to see Robert Storr2 and pitch him the idea, which we knew wouldn't get approved, but it seemed like a fun idea at the time. Kendell Geers3 gave me some money to buy a plane ticket.

J.G. So you were framing these pitches and actions, at least internally, as an artwork or artworks?

E.Y.

Everything was art – all of the performative things that we did.

Of course, we knew we didn't stand a chance, but we just flew there, had a half-hour meeting, and flew back home. That kind of thing was the work. I suppose that's where this mural came from – it came from that little trip and the misspelling.

J.G. Let’s hold for a moment on that performativity, that energy to use art to do things even if those things may not be overtly shareable. But here we are many years later, and it is on record. Was there a time when that kind of energy dissolved? Did that capacity to use art as a mechanism for stepping into some absurd gesture – traversing the Atlantic in this instance – did it change shape for you?

E.Y. It did. I don't necessarily know why or how it did, but it feels like the interest in that kind of work lessened. Even though I have found, and still find, this kind of work to be important, it is somewhat regarded as frivolous. More so these days. The art world is pretty one-dimensional at the moment, in my view. It will change again.

I think we go through these stages of ephemeral gestures, and then we go through stages of marketable objects. That's just how it is. I think once the market is dictating things, certain works are seen as serious and others seem like they are in jest.

I liked the work at the time because it did have these paths of interest, even though a lot of it was not shared and framed that way then. I don’t think I ever told the story of the trip to New York as being a part of this work. We were doing a lot of similar acts at the time. For example, whenever I was in a new country I would go and find a karaoke bar and sing one specific song to an audience of none. That performance, that gesture, was constantly ongoing and repeated. For me, that work worked because no one knew about it, but I had to keep it in the same kind of vein, keep it consistent. It's not just a thing that I can imagine happening. It's very much: I must now go and do this thing. No one must know about it.

K.M. I like that these gestures existed in contrast to your writing at that time for Artthrob, documenting your travels and the exhibition openings you attended. It's interesting that you separated your actions; some things could be known about, and some things not…

E.Y.

There's something about doing things that don't do anything.

But the travels being documented were also…a lot of that was completely fabricated. Some of it was just ideas that would pop into my head, and I’d be like, that happened, let’s go with that. That was also part of that kind of performance.

But to get back to the question, interest has waned in that kind of art production, the question of how much work is work. At the time, I was doing a lot of those performances about doing nothing. While I was sitting with a bunch of students at Michaelis, I began thinking about what the most minimal and most effective gesture could be. I was still teaching – I think it was a performance elective. I would say to the students that, for me, the ultimate performance would be to be invited to an international show to go drink the wine, to be a spectator but to also be a performer, do nothing, and then to come back home. I did that a few times, and people thought it was good. I editioned that performance, Do Nothing (2004), because otherwise, I thought, I’d be doing that for the rest of my life. For me, at the time, that was the ultimate work, the least amount of effort to do a very important thing. In my mind, at least – probably not in other people’s minds. I think the last edition was the one I gave to Andrew Lamprecht for his birthday, which was never performed.

The thought was, when does the least become the most? And when does it become labour?

J.G. There’s a sort of joke there: Nothing was happening and it didn't do anything. But it did do things because it naturally challenged people around what art could be and opened up something. The parallel question is, what kind of support structure needs to be there to hold those ideas over time? As you're talking, I'm thinking of Barend De Wet 4, for example, and the influence of someone like him in this arena of work, playing with the intersection of art and life. Of course, he and Christian had a relationship – another intellectual or artistic companionship doing things that create a community around a sort of proposition of action. There are others.

Whether in the zone of absurdity or the zone of some kind of resistance or protest against existing systems, there was a community at play, and it feels like that community held those ideas and made them relevant, together. I LOVE NEW WORK is aware of the community who ‘make’ relevance, the tongue-in-cheek reference to collectors saying things like, Oh, I love new work, and I want the new stuff. And then, of course, there are the collectors who say, oh, the new stuff is not as good as the old stuff. That whole game, which I always assumed was the play of the work. Wendy Fisher, A4’s patron, loved that – got that joke. Do you think the community of practitioners around that time, who invested in that mode, are not around anymore to the same extent? The community of artists today are not negotiating those ideas, and, as a result, there's less scaffolding for them. In a way, we're trying to understand how we can provide support for these gestures because they seem relevant and important to us.

E.Y. I guess you've answered your question, which is something I didn't really think about, and it’s absolutely right.

It was that community that provided the structure. Actually, it's twofold – it's about community but also about interest. And as soon as there's a lack of interest in that type of work, it falls apart. And then the community falls apart. People went their separate ways.

In the beginning, we had a very big, strong structure. I’m thinking of 2666 Studios, where everyone with a similar mindset would come together and work in that space and develop and collaborate and host talks and do whatever. Barend was there, as well as Christian. Douglas Gimburg6 was translating the Satanic Bible into Afrikaans – just weird stuff going on. I don’t know what it is that made the work less interesting to people. To me, it’s not any less interesting now.

K.M. I think that you've become that person for other, younger practitioners, like Luca Evans and Mitchell Gilbert Messina, sharing the permission to be able to make something that's absurd or that will be perceived as silly. Of course, they're not working in as conceptual a manner as you were, but there is the feeling that it's okay to just make a ‘silly joke’ and for that silly joke to be accepted as labour.

E.Y. I'm very happy to see artists using satire and humour because these are powerful tools. But I'm worried that in the current beige art market, it's frowned upon, people feel it makes light of the seriousness of what big galleries do. It shouldn’t – it should be thought of as a companion.

K.M. I was also thinking –

let’s imagine an alternate reality where you'd been completely embraced by the art world, and everyone loved your work and still loves it. That would have neutralised it. What made it subversive was the idea of running into rejection.

J.G. Your approach and Barend’s approach and Christian's approach could speak to each other because they toyed within the same self-constructed logical framework. I think this kind of performance practice relies on being inward-looking (as different to what are perhaps the more ‘outward-looking’ practices seeking affirmation from galleries, market forces, audience) and relying on each other to ‘get the joke’. I don't mean that it's all a joke or all silly or funny, but that this kind of practice was refined inside of a collegial community of meaning.

K.M. How did you and the others financially support this kind of conceptual performance of practice without making objects?

E.Y. We really didn't have a lot of money. We just made do. And I think that a lot of the travel was possible because someone would help out, or they were funded by exhibitions… Christian has always worked with a kind of barter system. He never worked with money. And I think that’s partly to do with his relationship with Kathryn Smith5. They have a system. Everyone did things to support themselves that were not related to art. And then, every now and again, you would sell a work. Of course, there were some objects. Wendy bought I LOVE NEW WORK. Patrons like her kept a lot of young artists’ work alive at that time. And everyone had an installation job or something on the side, and they still do.

J.G. Linda Givon6 was involved in Christian’s No Problems in Africa project. There was fuel provided by people who were actually engaged in patronage, being real patrons, saying to artists, Your work is interesting. You are interesting, even if no one understands exactly why. I'm going to back you.

E.Y. Yeah, we had different ways of doing it. I remember Christian and I were in Johannesburg about to go to Tanzania. He went to Goodman Gallery when it was still owned by Linda, and then he came back and said, Oh, here's a cheque. I said, Wow, how did you do that? and he said that he had told Linda about the project, and she loved it and wanted to support it with no strings attached.

J.G. I think her line, if I remember correctly, was something like, Go do it properly.

There are not many of those kinds of patrons around any longer, and there's definitely a shortage of that kind of engagement, which hinges in some way on being less object-focused and more committed to the unique ideas of individuals: that art’s other kinds of work, even if obscure, deserves a moment to breathe. That's a unique form of patronage; it’s not just transactional. No one was expecting anything back.

Linda probably was thinking, If you come back, that would be great.

E.Y. Yeah, that was the thing with Linda – and with Kendell. And there were other ways. When we were in Tanzania, we didn’t have a lot of money left, but just enough to get home. I said to Christian, If we take this money and go to a casino and put it on the red and double the money, we stay a bit longer. If we lose it, we just go home. He said, Cool. It's a chance. And then I put it on red, doubled it, and we carried on with the research.

J.G. Was it the case at the time, or would you be open to retroactively framing that gesture as an artwork?

E.Y. At the time, it was already a work.

Like everything we were doing then, we were always trying to frame it as work. It was a strange way of living.

Christian and I went to visit Barend on his farm in Plettenberg Bay while he was living out there, and everything we did there, from braaing to beekeeping, was documented and really considered as work being done. When we got into the car and drove to Plett for a week, we understood ‘the project’.

J.G. I'm curious about the archive – the inventory, for lack of a better word – of those actions. That documentation may exist, but it doesn't exist in our broader vocabulary. It's really encouraging to counter the conception we have of what art looks and feels like in this context with a kind of parallel history. But it needs bulk in order for it to become an interface. We need more data points to offer that kind of historical offset in the very practical way of an artwork. We need to draw out those actions, even if not all of them will feel as relevant so that one can really frame up this idea – which I love – that you just knew that everything was in some way using that paradigm to move things forward.

E.Y.

It was an interesting time. Everything felt like one piece of work. It was kind of an orchestra of things:

waking up in the morning and starting the day was part of that process, and whatever came through that… We’d get to the studio, and Douglas and Christian would be cooking up some weird exhibition or whatever. Everyone was saying, Why did you guys come up with this? But one thing would just kind of feed into the next. It was a continual exploration of certain themes that would lead to certain things. It never felt like, Okay, we're gonna do one project now. Let's focus on this. It becomes different parts of one thing. I guess that has ended. But I’m not too nostalgic about trying to revive that kind of work. That's why I talk about my retirement. I am a Sunday Conceptualist. From time to time, I'll make a work, but it feels like I've done what I needed to do in that realm. It was done at a specific time when it needed to be done, and I feel that it had an impact. Even though it irritated a lot of people, it did shift discourse a little bit, those kinds of gestures, and people re-looked at what work could look like. There are always phases of that happening. I think this happened in the 90s, and it will probably happen again. When the ‘formal’ conversations become interesting, the extracurricular conversations become more interesting as well. It’s about kickstarting that kind of engagement.